|

The Future is DigitalBy David MeekMay 23, 2002

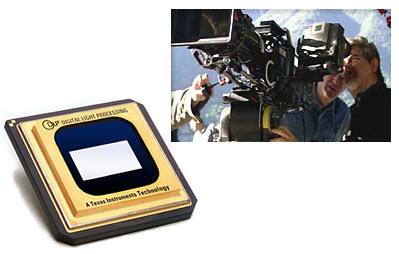

I have seen the future, and it is digital. At the outset, it is important that you understand I was firmly opposed to this concept. Before the events of this past weekend, I was completely, totally, 100% against the idea of digital projection. It couldn't possibly be good enough to take the place of film-based projection. It couldn't possibly have the resolution, the color, the depth of film. It just couldn't. Then I saw it for myself. What I saw wasn't quite as good as the best that film can provide. But it was much, much better than what film actually provides in the real world. (For those interested in a technological comparison and assessment of film-based and digital projection, I have created a sub-page for those so inclined. This link will open up a new window, which you may then close to come back to this article.) On Saturday afternoon, I drove out to Plano, Texas, to the Cinemark Legacy Theater. It is one of only 53 theaters in the United States to show Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones with digital projection. (The Cinemark Legacy, with its two digital screening rooms, is the only theater in the Dallas/Fort Worth market to show Episode II in digital...although there could have been a third screen in Dallas if Fox hadn't been extra greedy. [Second item in story.]) Having purchased my tickets in advance, I arrived a little over an hour early, and found an already-long line formed for the 4:30 show. Not a problem, as I like to sit close to the screen. This was even more important, as I planned to subject the Legacy's digital projection system to an up-close-and-personal examination. Going in, I fully expected the image to be highly pixilated, with washed-out color and problems showing "true" black-level images. This was based on the digital projection setups I had seen in the past. I was sure there was no way this setup could be any different. Boy, was I wrong. Don't misunderstand me; I'm not suggesting that the image was perfect (I'll get to that in a second). But it was so much better than anything I had expected. The color was rich and true to life (or, in the case of Episode II, true to fantasy). There was an incredible range of light and shadow; the smoke in one of the later Jedi battles was completely convincing. Dynamic images, fast pans and zooms, all rendered in a rock-solid cinematic style. As I examined on the technical sub-page, while the potential of film is greater than any existing digital technology, the real image as delivered in your local multiplex is far below that theoretical maximum. Comparing a standard film print showing in any multiplex to what I saw from that digital projector...it's no contest. The digital image totally outdoes the film image. As I said earlier, it's not that the digital image was perfect. In certain extreme cases, slight artifacts could be seen. Of course, I was deliberately looking for them, my eyes are sensitive to anomalies in the image, and I was in the fifth row of a theater with a screen about 20 feet tall and 50 feet wide. And the problems were actually quite slight; some pixilation on the edges of hard, straight lines of contrasting colors (like the closing credits and the horizon crawl of the opening), and shots with distant scenes brightly lit but out of focus. Quite frankly, I doubt that more than one percent of the people in the audience would have noticed any of these problems (or that it would have bothered them even if they did notice). For the sake of comparison, while the digital experience was still fresh in my mind, I went to a closer multiplex the next day and saw a standard film print of About a Boy (On a side note, I highly recommend the film). What I saw solidified my perception of the superiority of the digital projection system. Focus problems; excessive gate jitter, where the image shakes slightly on the screen, most noticeably during opening and closing titles, but sometimes throughout the film...and this was a print that had been shown no more than ten times before Sunday afternoon! It wasn't a print that had run for months. And the multiplex was actually one of the better facilities in the area. While not the best real-world projection I've run across (some of the smaller art-house setups are remarkably well-run), it was an instructive comparison: A multiplex that would certainly be in the top 80-90% of the total range of theaters in the country, showing a film on its third day of release...and it already looks significantly worse than a digitally-projected film. The question at hand, then, is: Why is digital projection better for the moviegoer in the real world? The problem stems from the difference between the ideal film presentation and what we actually get. Fifty years ago, commercial theaters were still mostly one- and two-screen facilities. They had well-made and well-maintained equipment, run primarily by union projectionists. These guys (virtually all were male) knew everything there was to know about projectors. They could take projectors apart and rebuild them unassisted. The projectionists knew how each component operated, and how to fix them if they broke or weren't running properly. And most importantly, their union was strong enough to dictate a maximum number of projectors each projectionist could cover, ensuring a constant presence in the booth. Starting in the 1960s, however, the theaters gained the upper hand with the introduction of the platter system, a device that takes the separate reels of a film, strings them together into one long spool, then runs it continuously from start to finish without the need for any intervention. Before the platter system, projectionists ran changeover projectors, shifting the film from one reel to another throughout the show. This required a projectionist be in the booth at all times to make the reel changes. The platter system eliminated this requirement. The result was the theaters crushed the projectionists' union, the process of handling projection was given over to untrained workers - frequently concession workers or the theaters' managers themselves - and the quality of presentation has never recovered. Because the platter system is designed to run unaided, and therefore reduce the labor costs of the theater, no one is consistently present in the projection booth during the course of a showing. If the projector has a problem, no one is waiting to correct it. If the lens shifts out of focus during a showing, someone from the audience has to get up and get someone to correct it. In the name of reduced expenses and increased profits, theaters now have the least-involved process possible with film. And this has produced horrible results in the nation's multiplexes. When projectors are well-maintained, run by knowledgeable staff members, and checked on frequently throughout each showing, the overall experience of film-based moviegoing can equal what the digital system can currently deliver. But the overwhelming majority of theaters have abdicated the most basic elements of presentation, producing the odd outcome that abandoning film entirely actually results in an improvement in the moviegoing experience. The Episode II showing also gave me a chance to see the range of looks that a digital theater can provide. And, as befitting a computer-based technology, the old adage applies: Garbage In, Garbage Out. Since Episode II was shot entirely by digital cameras, the digital projection system is optimized for that film. But we saw more than the film. We saw trailers for several films, blurbs for the digital technology companies behind the equipment, and the theater chain's "Welcome" segment. Each provided a different view of the future of digital projection. Starting with the blurbs for the digital companies, Technicolor Digital and Texas Instruments/DLP, the manufacturers of the data transmission system and projector in use, respectively: It was astounding. It was really clear that the images in use were 100% digital; they had never been transferred to film as part of the production. The images were clear, bright and amazing. Next in line were the trailers. We got The Matrix Reloaded and Minority Report. In the case of these trailers, both films were shot with standard film stock. So the trailers we saw were digitally scanned for presentation. In the case of the Matrix trailer, it was rock-solid and crystal clear. Minority Report was grainy, but that is inherent in the trailer itself (the film's action sequences seem to be intentionally dirtied up, an effect I saw when the trailer first appeared in theaters). In both cases, the digital system produced as much color and clarity as was available from the original. The bottom of the barrel was the Cinemark "Welcome" segment. This looked like someone held up a digital camcorder in another theater and dumped the results onto a CD-ROM. It was muddy, the colors were all off...it was just plain ugly. This points to a truism of the digital system: Unless the transfer from film to digital is done with great care, no system, regardless of price or complexity, can overcome poor source material. So where does this leave us? I believe we are on the threshold of a major advance in real-world cinema presentation. But, as is usually the case, there are major obstacles to be overcome. And the folks who stand to profit the most from this transition are standing on the sidelines: The motion picture studios. The reason the studios are interested in digital projection isn't an improved moviegoing experience for the audience. The studio interest in digital projection is purely financial. The cost of producing 4,000 to 6,000 prints for a major motion picture wide release adds millions of dollars to the post-production costs of the film. This expense - multiplied by the prints that must be produced for foreign markets, along with the various subtitles and replacement audio tracks - eats up a significant portion of studio profits for all but the biggest blockbusters. Anything that reduces their expenses is something the studio heads will champion. The key hurdle to overcome is financial, with a note of the scale involved. The estimated cost to convert one screening room from 35mm film to a digital projector setup is at least $75,000, and possibly over $100,000. If you consider the approximately 7,000 theaters in the US, virtually all with multiple screens, the total price tag could easily surpass $1 billion. And that doesn't address the Canadian market, much less the markets beyond North America. One of the dreams of a worldwide digital distribution network is true day/date releases of all films. But even if you can swallow the price tag of the US conversion, it pales in comparison to the cost and complexity of a worldwide installation. So where do we go from here? The article continues on page 2. |

Thursday, January 08, 2026

© 2006 Box Office Prophets, a division of One Of Us, Inc.