|

The Future is Digital (Technology Discussion)By David Meek

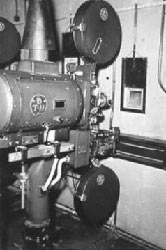

Note: this page contains supporting material for the Box Office Prophets article "The Future Is Digital". If you somehow ended up on this page without seeing the main article, you can still get there from here. In discussing digital projection, it's useful to take a look at both the digital technology involved and the technology behind the film-based standard we know and love. In this corner, you have film. Thirty-five millimeter motion-picture film, to be precise, the standard for US commercial exhibition since the 1920s. While the technology of recording images on film and producing numerous prints of those images has evolved in the last 100 years, the basic principles of motion-picture film have not. A camera, equipped with a shutter that opens and closes 24 times per second, records the image in front of the lens by a chemical transformation when light strikes the unexposed negative. The images, which are only visible once the negative has undergone a bath in various chemicals, are edited and then transferred to multiple prints. These complete copies of a film are shipped all across the country and around the world for presentation. The print is then threaded through a projector, and shown to a waiting audience. The projector is equipped with a rotating blade that interrupts the light from the massive xenon bulb 24 times per second. An intermittent, a set of teeth spaced to the exact dimensions of the sprocket holes on each side of the print, pulls the film forward one frame at a time. A lens placed in front of the film gate takes the projected image and expands it to the size of the screen in use. Every time a print is shown, - and each film is shown between four and seven times per day - it is subjected to this torture test: an intensely-hot lamp throws light through the print, deforming it slightly each time. The intermittent pulls on the sprocket holes, stretching them slightly on run after run. The storage mechanism adds additional tension to the print as it runs from one large platter to another. Various rollers and guides are frequently allowed to become unpolished and rough, scratching the print as it runs. And in most cases, the projection room is allowed to become dusty and dirty, causing the prints to accumulate dust and grime, which then gets worn in and baked on. In the other corner, you have digital projection. This is the new kid on the block. While the source material may vary (it may have been shot on standard film, created digitally like the Toy Story films, or shot digitally like Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones), the playback process is the same. The data is stored on optical or magnetic disks (high-capacity disks that function like DVDs, or on massive computer hard drives). The data is fed to a projection system which contains a digital display technology. While there are some competing approaches, the one that has clearly taken the lead in theaters is the digital light processing technology (DLP), developed by Texas Instruments. The heart of the DLP technology is an item called a digital micro-mirror device (DMD). The DMD is a computer chip with thousands and thousands of tiny mirrors, each individually controlled. The DLP system controls each tiny mirror, telling it to point up, causing light to be reflected, or to point away, causing no light to be reflected. By moving these mirrors over a hundred times per second, the system can project a moving image onto a screen (For more information on the DLP technology, Texas Instruments has a site dedicated to their efforts). How does this compare to the film-based system which has been in use for a century? The only moving parts in a DLP-based projection system are the tiny mirrors and a color wheel (used to control the color being projected on the screen in the one-chip design). The digital projector does not have to physically interact with the film in question. A film projector, on the other hand, has to interact with the print each time it is shown. And every time it runs, it imparts some damage to the print. Even the best run projectors will, over time, deform and damage the prints that are run. Film prints are consumable items. They will, if shown repeatedly, be damaged. The key question seems to be is one system clearly better? This is a difficult question to answer. The theoretical maximum resolution of film is remarkably high. The individual crystals of the film print can be considered somewhat similar to the number of pixels of a digital projection technology, and no digital technology currently exists with the tens of millions of pixels it would take to match that theoretical maximum. However, the theoretical maximum resolution of film is greatly influenced by the realities of film presentation. A very common problem with film projectors is gate jitter. This occurs due to the exceedingly rapid pace of the intermittent pulling down the print one frame at a time, 24 times per second. The intermittent must, as its name implies, stop and start very quickly and accurately. The slightest deviation from the ideal can cause the frame to be in motion while the light is thrown through it. When the frame is not rock steady in the gate at the precise moment the frame is exposed to the light source, it will result in a shaking or "swimming" effect on the screen. This is increased by an incorrect setting of the tension on the gate itself, brass rails that press on the edges of the print to steady the frame while it runs through the gate. The result is that film's current advantage in resolution can be reduced or even eliminated by a shaky projected image. If the image isn't steady, the higher resolution is irrelevant, since you can't see the image clearly. In the case of digital projection, the image will be as steady as the source material. And since digital copies of film-based prints are made one frame at a time, no jitter should be introduced in that process. Digital projection can be steady as a rock. In fact, during this interview at The Digital Bits with writer/director John Landis, he comments on what stuck out for him in a digitally-projected film: "What's interesting is the first time I saw digital projection of a feature, I kept thinking, 'What is wrong?' I was looking at the screen thinking, 'What's bothering me?' And what was bothering me, it was so strange, was that the main title was rock steady. There was no gate jitter. But I don't think people should freak and think, 'Oh God, we're going to lose [something],' 'cause we're not." |

Friday, December 19, 2025

© 2006 Box Office Prophets, a division of One Of Us, Inc.