|

The Future is Digital (Page 2)By David Meek

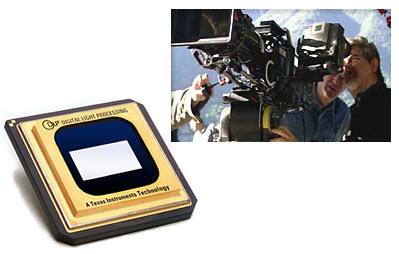

Note: This is page 2 of the Box Office Prophets article "The Future Is Digital". If you somehow ended up on this page without starting on page 1, you can still get there from here. So the question, as most of these problems boil down to, is who will pay for this transition to digital projection? After analyzing the situation, I perceive there to be three main possibilities. Each is outlined below. Possibility #1: The studios pay for it. This is, at the outset, the least likely of all these scenarios. Yet in many ways, it is the one that makes the most sense. Consider: Who will truly benefit from the digital transition? We as moviegoers will benefit from a more consistent presentation of movies. The theater owners will benefit from the reduction of staff effort involved with the preparation, presentation, and breakdown of films each week. Instead of assembling the five or six reels of a normal film on a platter system, paying someone to be there to thread up the projector between each showing, then tearing the film back down to its original reels for shipping, the theater just has to have someone keep tabs on the digital linkup - satellite or landline, this is unknown at this time - and get the data loaded into each projector. But this is a miniscule portion of the theaters' expenses. No, the largest benefit will be realized by the studios. They will no longer have to pay print labs to produce thousands of copies of their films. They will no longer have to pay the shipping costs of moving these films all over the country and the world (A six-reel film weighs a heck of a lot). And they will no longer have to be concerned if a print gets damaged (Currently, since the theaters lease the prints from the studios, the studios are responsible for shipping out replacement reels to theaters if the print is damaged). The total savings to the studios would be astronomical. In fact, the total savings over several years would probably come rather close to the cost of installing the equipment in the first place. Of course, this is exactly the kind of thinking that studios don't want to hear. But if you think it through, it really does make sense: The studios will be the ones to receive the greatest benefit from the change, so why not have them pay for the transition with the savings? Here's my idea. As the digital implementation takes hold, the studios will start to pay less and less in terms of print and distribution costs. The savings realized by this transition would pay for the cost of the equipment. Let's set a six-year window, starting with the largest markets. Each year, a certain number of theaters get digital installations, paid for by the studios. The studio outlays the cost of that equipment, with the knowledge that the theater is one less they have to spend money on in producing and distributing physical prints. As fewer film-based theaters remain, there will be even more money available to speed the transition. And once the transition is complete, 100% of the savings are now back in the pockets of the studios. To avoid the possibility of collusion and undue influence on the theater companies, an independent company would need to be established, funded by all of the studios. This company would oversee the process of converting the nation's theaters to digital projection. Once the process is complete, the company would either dissolve or change missions to address the conversion beyond the US market. The problem is that the studios seem to believe that they can remain on the sidelines, that the market will somehow take care of this transition. But with the theater companies in such dire financial straits after their disastrous overbuilding binge of the 1990s, presuming that the theater owners will wake up one day and say to themselves, "Hey! Why don't we spend millions of dollars to convert our theaters to digital projection?" is remarkably naïve. Possibility #2: The theaters pay for the conversion themselves. As mentioned above, this is somewhat unlikely due to the bankruptcy and near-bankruptcy that most theater companies have been facing over the last year or two. In the midst of a financial crisis this large, for the studios to expect the theaters to pay for a $1 billion overhaul, just to reduce the expenses of the studios, is insane. That's not to say that the studios won't have their way. But if a stalemate occurs, it could be decades before we see a large-scale transition take place. One way out - again, this is not a plan the studios would like to have discussed - is for the studios to pass along part of the savings to the theaters, either as some kind of annual rebate or in reduced gross-percentage formulas (Theaters lease prints from the studios, and in turn give back to the studios a weighted amount of money, either a minimum guaranteed amount or a percentage of the gross box-office receipts, whichever is higher. With the exception of repertory houses and college film programs, the gross percentage is higher and gets paid). If the studios would reduce the percentage the theaters have to pay back each week, the theaters might be able to get financing to buy the projectors and equipment themselves, since they would be keeping more money in their own pockets each week. Or if the studio agreed to make a yearly restitution payment to compensate the theaters for buying the equipment, financing might be made available based on this guarantee. One way or another, the theaters have to see their investment as making good financial sense for them, or they have to be forced by outside pressures to do so (I touch on this at the end). Possibility #3: A third party purchases, installs and maintains the equipment in the theaters, and receives a portion of the theater's net box-office proceeds (after the studios get their initial cut). This model has the theaters leasing the equipment at no initial cost to them. By giving up a percentage of their box-office profits, they make the transition with no capital outlay on their part. Again, with the bankruptcy status of several chains, this may be the only way this can happen in the short term. I did think of this approach several years ago, but didn't manage to corner the market, much less write the idea down. Which is a shame, since I could have been ahead of the curve: Technicolor Digital announced plans to go into this field as part of their long-term survival strategy. Since the days of motion-picture film laboratories would be at a near-end, Technicolor needed to do something to establish a place in the digital future. The real problem I see is one of scale: Can any one company - or several - get over $1 billion in capitalization to carry out a scheme of this magnitude? It seems to me that this will only work in a more limited realm; major theaters in large markets might be able to swing this. But whether or not any profit-minded company would invest hundreds of thousands of dollars to convert theaters in small markets, where a percentage of box office-profits to be returned is remarkably low, is really uncertain. Of course, the one thing that the studios and theaters will agree on is passing the expense of the conversion on to the moviegoing public through higher ticket prices. In fact, no matter how the process is actually funded, this is a virtual certainty. However, should the theaters and studios pass the expense on to moviegoers? Although we will benefit from improved movie presentation, is it appropriate to make us pay to fund the studios' cost-savings? Of course, the answer is no. But it will happen, just the same. The only question is how much will the increase be? One dollar? Five? Ten? I think much over $1-2 won't fly. But having seen it for myself, I would personally pay an extra $1 a ticket. Even though I'd be muttering under my breath every time. The digital transition makes so much sense for so many reasons. But the major players - the studios and the theater companies - have to get together to make this a reality. My finger is pointing squarely at the studios; they must come forward with some involvement if they want to make digital presentation a reality. But what can we, as moviegoers, do about this apparent standoff? I think there are lessons to be learned from the digital sound revolution of the 1990s. In the events that led to the near-standard implementation of Dolby Digital and DTS equipment in multiplexes across the country, we see the seeds of moviegoers - and moviemakers - forcing the Powers That Be to make significant changes. In the very early 1990s, digital sound systems in theaters were a novelty. In large cities, there might be two or three screening rooms at most with the equipment to reproduce a digital soundtrack, and there were only a handful of films released with the digital soundtracks to play. What led us from there to here? I see two different reasons for the overwhelming change. The first had to do with moviegoers. Once we heard a film presented in Dolby Digital or DTS, we could tell there was a difference. Of course, studios used the technologies on their most bombastic soundtracks, making the difference even more significant. And once we knew what those terms and phrases meant - digital sound, 5.1 Surround - we started to seek the theaters out. We looked in the movie listings and chose to drive across town to the theater with the digital setup, instead of going to the closer theater. When attending movies at theaters without digital sound systems, we asked when they were getting this technology. In short, we collectively exercised our financial power, spending our dollars where the technology was located. We voted with our feet. The other reason for the change was driven by the people behind the cameras: the directors. Actually, if you want to be specific, it was one director in particular: Steven Spielberg. Spielberg became involved with DTS, an up-and-coming competitor to Dolby Digital. The problem was that many theaters that had the money to spend had already purchased the Dolby Digital systems or were sitting on the sidelines. The solution? A dual-carrot approach: DTS offered its equipment to thousands of theaters across the country at greatly reduced prices, and then hyped the new format in ads for the first Jurassic Park movie. Audiences were primed to seek out Jurassic Park in DTS, increasing the inclination of theaters to buy into DTS. So far, no one is currently offering similar large across-the-board discounts on the digital projection equipment to encourage early adoption of the format. How does this affect digital projection? The director in question this time around is George Lucas. In 1999, on the release of Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace, he announced that he was shooting Episode II entirely in digital, and that only digital theaters would be permitted to show Episode II when it opened in 2002. At that time, there were only about 20 digital-equipped theaters in the country. Flash forward to today...and a grand total of 53 has been reached. Lucas relented on Episode II, allowing film-based presentations to take place. But he has renewed his threat for Episode III, coming in 2005; only digital theaters will get his film. The question is whether or not Lucas' contract with Fox will allow him to dictate theater choice to that level. Fox has allowed Lucas to place strong restrictions on Episode I and II theaters (must have Dolby Digital or DTS systems, must have a certain level of projection equipment, etc.). But it remains to be seen if, in 2005, Lucas can force Fox to open Episode III only on whatever number of digital screens exist at that time. Would Fox allow Episode III to open on only 1,000 screens? Five hundred screens? Two hundred? Of course, the threat might help goad both the studios and the theater companies to the bargaining table. But in my opinion, the ball is clearly in the studios' court. If they don't step forward, claim ownership of this issue, and establish a fair and equitable approach to digital renovations, then the promise that I saw that day will be for naught. In closing, I will return to my starting comments. I went into this weekend philosophically tied to film-based projection. I worked as a projectionist for three years, and came to love the format. There's something magical about film, about the mechanism whirring away, about the flickering images on a huge screen in a darkened room. And even though my love for film will never go away, I now realize that the future is not in film, but with digital. And that future isn't nearly as bad as I had once imagined. |

Friday, January 02, 2026

© 2006 Box Office Prophets, a division of One Of Us, Inc.