Johnny Carson: An Appreciation

By Stephanie Star Smith

January 7, 2006

The king is dead.

That line, stolen from a classic Carson bit, pretty much describes the feelings of many on the morning of January 23rd, when they awoke to the news that Johnny Carson, the Once and Future King of Late Night Television, had died of emphysema.

Words like "icon", "legend" and "national "treasure" are used so frequently in the breathless prose of PR flacks and entertainment-news show anchors that they have nearly come to lose all meaning. But when those words started floating around on that Sunday morning, they were being used in all earnestness, and it could be said that those words, and the many other superlatives employed, weren't nearly adequate enough. Because the world lost a unique talent who quite literally changed the way people watched TV, and whose departure from the TV landscape signaled a sea change the repercussions of which are still seen to this day.

But to look at Johnny Carson's background, and particularly his early show-business career, one would hardly have thought he'd one day achieve such status.

John William Carson was born on October 23, 1925 in Corning, Iowa. When he was eight, his family moved to Norfolk, Nebraska, which Johnny considered his hometown. His first foray into show business was when he ordered a kit of magic tricks from the back of a magazine when he was 12; wearing the cape his mother made him and calling himself The Great Carsoni, he made appearances at Elks lodges and other local events throughout his teens. After serving in the Navy in World War II, Johnny decided to use the newly-minted GI benefits to get a bachelor's degree from the University of Nebraska. Upon graduation, Johnny went to work for radio station WOW in Omaha. In those days, being a DJ meant little more than back-listing or intro-ing the songs, and there was little to keep such an agile comic mind occupied.

But Johnny found places to employ his comedic talents. Back in the late ‘40s/early ‘50s, when the studio system was still in existence, stars weren't allowed off their leashes in public, and even if shows like Tonight had existed back then, no studio publicist who wanted to keep his or her job would have let a star go on one. Everything was tightly controlled by the studios, and promotional interviews for upcoming films were no exception. The studio people would tape interviews with stars and then send the audio tapes to local radio stations, along with the list of questions that were asked in the original interview. Decidedly boring stuff, until Johnny got the bright idea of putting in his own questions, resulting in some pretty embarrassing, and hysterical, responses being made of the pre-taped pabulum.

It was around this time that Fate made her first intervention in Johnny's career. WOW, like many local radio stations in the late ‘40s, was experimenting with this new-fangled technology known as television. They had six hours of programming a day to fill, and were pretty much willing to put anyone on the air that had an idea for a show. Johnny had one: a variety show format called The Squirrel's Nest, with Johnny doing comic skits and interviewing whoever happened to stop by. In form, Squirrel's Nest was remarkably like what the Tonight Show would become when Johnny took over as host, except the guests that sat on his couch at Squirrel's Nest tended to be about as far from celebrities as you could get. But the show did help him hone the interview and ad-lib skills that would serve him in such good stead years later.

He did get the idea that he should try his hand at really working in show business, and so it was that, like many a young Midwesterner, Johnny packed up his family and headed to Los Angeles in 1950, to see if he could make a go of it in television. He managed to talk his way into a local show at the CBS O&O, which was then going by the call letters KNXT, called Carson's Cellar. This Sunday afternoon show was pretty much The Squirrel's Nest, West Coast Edition, with Johnny's monologue and skits, and whatever acts Johnny could get to appear. Fate took a hand Johnny's career arc once again when Red Skelton happened across Carson's Cellar one Sunday afternoon and loved what he saw so much that he showed up at the KNXT studios the following week, asking to be on the show. The word got out in the comic community that this was the show and rising comedy star to be seen with, and before long such luminaries - and Carson childhood idols - as Groucho Marx and Jack Benny were making (unpaid) appearances. When the show finally folded in 1953, Red Skelton hired Johnny for the writing staff of his CBS primetime show.

It was during his stint as a writer for Red Skelton that Fate stepped in once more. One afternoon, Skelton was rehearsing a skit in which he was to walk through a breakaway door; unfortunately, the door didn't break away, and Skelton was knocked unconscious. With their star down for the count with a concussion, and a live show going on in just a few hours, the show's producers frantically looked for someone to stand in. It's not known whether Red Skelton recommended Johnny or if perhaps one of the producers had seen Carson's Cellar, but Johnny was tapped to take over for the night, and like the proverbial Broadway saga, he went before the cameras as a virtual unknown, but came back a television star, with Jack Benny reportedly telling friends, "That kid is great, just great...you better watch that Carson kid".

The newly-minted star, however, had some trouble finding his niche. CBS first tried Carson as a game-show host on Earn Your Vacation, but the show failed to catch on. Next it was The Johnny Carson Show, a variety show much like the ones Red Skelton and Jackie Gleason had at the time. But sketch comic though he was, the show was still an uneasy fit for Johnny, and that, too, quickly sank. Feeling he'd tried everything that could be offered in Los Angeles, Johnny headed back East to New York, the center of television production at that time, and made guest appearances on several shows. It was in New York that Fate would make her final machinations in anointing Johnny Carson a bona fide star. Much as would happen during his own reign, NBC asked Johnny to guest-host for Jack Paar on the Tonight Show during one of Paar's vacations; it was obvious to all who watched that show and talent perfectly meshed, and Johnny had found a show business home. But Paar and NBC were still on speaking terms at that point, so Johnny was back in the job pool. It was at this point ABC tapped Johnny as host of a game show called Who Do You Trust? The format for Who Do You Trust? was loose enough that Johnny could interact with the contestants, displaying his nimble comic mind and impeccable timing much the same as Groucho did on You Bet Your Life. Finally the star that had been forming was now born. Who Do You Trust? also provided Johnny with one more element he needed for his eventual move over to Tonight, for it was on this show that he met his soon-to-be-long-time announcer and sidekick, Ed McMahon. The pair embarked on a professional and personal relationship that would outlast both their marriages and continue until the end of Johnny's life.

When the mercurial Jack Paar decided he'd had enough of fighting with NBC and that he'd leave the Tonight Show, the network immediately tapped the young man who'd done such an impressive job of filling in for Paar. But Johnny wasn't any too sure he wanted to try and fill Paar's somewhat large shoes; in fact, he viewed the position as something akin to career suicide. But thankfully for us all, NBC persisted, and finally Johnny agreed. Due to ABC refusing to let him out of his contract, six months would lapse between the time Jack Paar left Tonight and October 1, 1962, when Johnny Carson officially took over. Although the kinescopes of these early shows are forever lost - some idiot at NBC in the late ‘60s decided to free up room in the vaults by tossing old shows, thinking "no one will ever want these" - stills and stories from those early days still exist. Johnny was introduced to America as the official new host by one of his childhood idols, Groucho Marx, with another boyhood idol, Jack Benny, guesting later that week. Both Groucho and Jack Benny would continue as frequent guests until their deaths.

The Tonight Show became the place to be seen for established acts and rising stars alike. In fact, to be on Tonight was the break for comedians in that time before HBO and Comedy Central existed. The list of comedians whose careers he started or revitalized reads like a who's-who of comedy for the latter half of the 20th century: Don Rickles, David Letterman, Rodney Dangerfield, Gary Shandling, Tim Allen, Jerry Seinfeld, Roseanne Barr, Joan Rivers, Billy Crystal, Ellen DeGeneres, Jay Leno, Steve Martin and Drew Carey all benefited from being on Tonight. That five- or ten-minute slot was, as Jerry Seinfeld said after Johnny's death, your golden ticket into show business; if Johnny liked you, you had arrived. That full-throated cackle, the post-act comment on how funny you were, these were stamps of approval. But the absolute pinnacle of success was the wave over to sit on the couch for a few moments and talk; that was the Holy Grail of the comic, for it meant Johnny thought you were that good. All comics were told to look for the wave, but most wouldn't see it for several appearances; only rarely would the honor of being called to the desk after a first appearance be granted. This fact was rather sweetly demonstrated during Drew Carey's first appearance on the Tonight Show. At the end of his set, with the audience still howling with laughter, Drew looked desk-ward as instructed, and Johnny gave him the coveted wave over. Drew does a double-take, then points to himself and actually says, "Me?", as though Johnny might have been gesturing to someone else. Drew Carey made an even greater impression on both host and audience when, obviously nervous, he answered Johnny's comment on how funny Drew was with, "Thanks. So are you", and was rewarded with that cackle.

It wasn't just comedians whose careers Johnny Carson made on Tonight. Bette Midler was singing in bath houses in New York when one of Tonight's talent bookers saw her act and invited her and her pianist on the show. Johnny took an instant liking to her, having her back several times and helping to launch the Divine Miss M persona. It also gave a leg up on her pianist's career as well, a guy named Barry Manilow; perhaps you've heard of him. And it was Bette who was the final guest on Johnny's penultimate Tonight Show, serenading him off in her trademark style, even sharing a duet on one of Johnny's favorite songs, Here's That Rainy Day.

The Tonight Show has been characterized as a glitzy Hollywood cocktail party to which the nation was invited, and there is some truth to that. Certainly the stars that were booked time and again were the ones capable of holding a conversation outside of their next film or their series; the stars that entertained Johnny came back, and as it turned out, the stars that entertained Johnny were also the stars that entertained us.

Of course, it wasn't just stars who sat on Johnny's couch. Like any good variety show, Tonight under Johnny featured ordinary people who had unusual talents or oddball collections. One of Johnny's favorite annual bookings were the winners of the national bird-calling competition, a group of youngsters who did various bird calls. There was the guest who billed himself as a manualist; he "played" songs using the noises he made with his hands, and did a hysterical rendition of The Star-Spangled Banner. There was the lady who made portraits out of walnut shells, and the lady who collected potato chips that looked like - to her, at least - famous people. Of course, the potato-chip lady was the perfect set-up for a joke, and Johnny couldn't resist; he'd hidden a bowl of potato chips under his desk, and when Ed McMahon distracted the woman for a second, Johnny quickly grabbed one of his chips and crunched it rather noisily. The expression on the woman's face was priceless, as was Carson's feigned innocence in believing the lady wouldn't think he'd eaten one of her chips. TV Guide, in fact, tabbed this as the funniest moment on television.

One thing that set Johnny apart was that he treated everyone who sat on that couch - and later in that chair next to the desk - with respect; from celebrity to politician to scientist to author to regular person, all were allowed to keep their dignity. He never ambushed guests with questions on topics they had requested not be discussed; he saw no reason to make a guest uncomfortable, especially when it would have detrimental affects on the show. And he never patronized the regular people, either; when he made a joke during the appearance of a non-show biz person, he was never cruel or condescending. In fact, one almost can't say he made a joke at someone else's expense, because there was never that sneer or air of superiority, never the intimation that he was "too cool" to deal with this sort to thing, no winking at the audience that this person should be an object of ridicule. He made jokes because he was a gifted comic who simply couldn't pass up an opportunity for a laugh, because laughs made the show, and Johnny was all about the show. The fact that Carson made at least as many jokes about himself as he ever did about others made the atmosphere on the Tonight Show all the friendlier, and one that both viewers and performers wanted to return to again and again. Johnny never made a guest look bad, and at times went out of his way to make guests look good. He never played Can You Top This? with guests, never belittled them or tried to get in a zinger or outshine a guest. It's not that Johnny didn't have an ego, but rather that he realized that making the guests look good made the show look good, and making the show look good, in turn, made him look good. He never lost sight of that, and it's one of the things that made his Tonight Show into the institution that it became.

It was Johnny's steadfast refusal to ever demean a guest or treat a guest with anything other than respect that prompted many stars to come on Tonight to make personal announcements or discuss delicate matters from their private lives; they knew that Johnny would go into the subject only as far as they were comfortable, and never press for more. Tiny Tim's wedding on the Tonight Show has become legendary, but there are other milestones that are perhaps less well-known, but more indicative of the man Johnny Carson was. The story of Michael Landon's battle with cancer is one such. When it became known publicly that Michael Landon had terminal pancreatic cancer, every news outlet and journalist in town wanted to interview him about it. When Landon decided he was ready to talk, however, he chose to come on the Tonight Show, and during his appearance, he told the audience why. Over the years and his many appearances on Tonight, Landon and Johnny had become friends. In the midst of all the "Tell us your story first" calls from others came a call from Johnny. Not asking Landon to appear on the show, but asking what Johnny could do for him.

Such was the measure of the man, and one of things that kept his star on the rise even after he himself left the spotlight.

If The Tonight Show was America's glimpse into a Hollywood cocktail party hosted by a family friend, then the monologue was America's window onto the important happenings of the day. While the rest of Tonight was middle-of-the-road and apolitical, the nightly monologue was as topical and acerbic as they come. It was reported many times that Johnny read five to six newspapers a day, making notes of what events would make good monologue jokes, then he'd pull together the (hopefully) best ten minutes of material to open the show. It was the one facet of the show that was wholly his, and it was also the one area of the show where Johnny Carson's personal views on politics and world events were expressed. The monologue was a bellwether of what was important in America, and as Johnny went, so went the nation. There are those who say that it was Johnny's relentless week-nightly hammering of Richard Nixon that brought that presidency down, and while that's rather a lot to lay at one comedian's doorstep, there is no denying that Johnny's pointed material on Watergate fueled the nation's distrust of the Nixon Administration, and likely helped bring about Nixon's resignation. Johnny's monologue was considered so influential that McDonald's once threatened to sue him after a monologue joke making fun of the lack of heft of the fast-food chain's burgers. A joke one night about the possibility of a toilet paper shortage caused such a run on toilet paper the next day that an actual, albeit temporary, shortage was created. Johnny spoke, and America listened. But they didn't always laugh, and it was at those times that Carson really shined: whether it was an off-the-cuff comment, a bit of soft-shoe to Tea for Two, or sometimes just a look, it didn't take Johnny long to win an audience back after a joke bombed. His recoveries were so successful, in fact, that some comics suspected he wrote jokes he knew would bomb, just so he could trot out one of his saves.

Having begun his career as a joke-writer and sketch comedian, Johnny created many characters and routines for Tonight that the audience came to cherish: the mentalist Carnac the Magnificent; the oily Art Fern, host of Tea-Time Movie and huckster extraordinaire; Aunt Blabby, the cantankerous old woman to which Jonathan Winters gave more than a passing nod when creating one of his characters; Floyd R. Turbow, a clueless redneck who loved to take advantage of the Fairness Doctrine, and invariably ended up making a mess out of whatever it was he was objecting to, or defending. There was also his dead-on Ronald Reagan impersonation, which was employed in many a sketch during Reagan's years in the White House, including a memorable updated rendition of Abbott and Costello's Who's On First? skit. There was the weeklong series of pie-throwing parodies of annoying commercials, culminating in the three-pie bashing of the guy who wanted to talk about diarrhea. And there was the Mighty Carson Art Players, Johnny's catchall name for silly skits involving celebrities; the classic Copper Clappers sketch with Jack Webb was one such memorable outing. There was Stump the Band, an audience-participation skit where members of the audience would try and stump Ed, Doc Severinsen and the Tonight Show band with obscure songs in order to win valuable prizes, even should they fail to stump the band. The fact that the audience came to know these routines so well that they could recite parts right along with the characters didn't matter; in fact, in this case, familiarity bred pleasure. We might not have known where all the jokes were headed, but we knew at some point, Carnac would put a Middle Eastern-sounding curse on the audience for failing to laugh; Art Fern would tell us to cut off our Slausons; Aunt Blabby would make some reference to being lonely and in need of sex, though not quite that blatantly; Floyd R. Turbow would make some mangled comparison as to why his viewpoint was the most American; and someone playing Stump the Band would turn down the ride in the Goodyear blimp. Even some of the unscripted moments became familiar through the anniversary shows: Ed Ames' famous tomahawk throw; George Gobel's line about being a pair of brown shoes; the mynah bird who called cats; the frightened marmoset that crawled on top of Johnny's head and proceeded to anoint him with what Johnny fervently hoped was saliva, but wasn't; the baby chimp that seemed so human in its actions that it sent Johnny into gales of laughter. We knew them all, and we loved them more each time we saw them.

There is an old show business adage that one should never work with children or animals, both being natural scene-stealers. But Johnny Carson never subscribed to that notion, likely because his quick wit allowed him to keep from being upstaged by the adorable antics of the kinder and the critters. As a result, both children and animals were frequent guests on Tonight. Joan Embry of the San Diego Zoo and Jim Fowler from Mutual of Omaha's Wild Kingdom were frequent guests on the show, bringing with them an assortment of animals to thrill the audience and the host. Johnny always interacted with the animals, and some of the highlight-reel moments include the boa constrictor that was a little too interested in the family jewels; the aforementioned marmoset; an medium-sized alligator that Jim Fowler left Johnny holding whilst he went back stage to get another creature; the obviously-scripted bit where Johnny viewed two leopards in a cage and commented that one had to maintain eye contact in order to show he was not afraid, only to run and jump in Ed McMahon's arms when one of the leopards growled and took a swipe at him.

Children, too, made many memorable appearances on Tonight, and the interviews were always delightful, mostly because again, Johnny did not talk down to or patronize the children; his questions, though geared to their age and intellect, were still respectful and designed to elicit information, not make jokes at the child's expense. One stand-out moment came when Johnny was interviewing a young math prodigy, and amazed the child by doing a magic trick where he made a quarter "disappear", only to pull it from the child's ear a moment later. When the boy asked how one really made money disappear, Carson's instant reply was, "By getting married."

For as much success as Johnny found professionally, he found little in his private life for many years. Johnny was married four times, beginning with his college sweetheart, Joan Wolcott, with whom he had three boys. When the middle child, Ricky, died in a car accident in 1991, Johnny took a few minutes at the end of his next show, begging the audience's "indulgence" of a grieving father, and shared some of Ricky's photographic work. It was one of the few times that a glimpse of the very private Johnny Carson was provided to the public. Johnny divorced Joan in 1963 and married Joanne Copeland; that marriage lasted nine years, and shortly after the couple divorced in 1972, Johnny married Joanna Holland, prompting some to joke that Johnny always married women whose names began with J so he wouldn't have to change the monogram on the towels. This marriage ended with the most contentious divorce; the protracted settlement negotiations were extensively covered by the tabloids, as well as relentlessly made fun of during Johnny's monologue; the case was finally settled in 1985, with Joanna receiving a sizeable sum. Johnny's fourth marriage, to Alexis Maas in 1987, not only broke the J-name cycle, but also seemed to be his most harmonious; they remained together until Johnny's death.

It has been said of the Tonight Show that Steve Allen invented it, Jack Paar refined it, and Johnny Carson defined it. Over three decades - making his version one of the longest-running shows in television history - Johnny built the Tonight Show into a powerhouse that consistently brought in more money for NBC than any of its other shows, that figure being as high as 20% of the network's revenues in years when the network's primetime shows weren't all that. He defeated all comers in the late-night wars, consistently beating younger and hipper hosts; these dust-ups had the meritorious effect of creating in Johnny the desire to bring his A game, and kept him from becoming too complacent. In fact, the only show that ever survived opposite Tonight during Johnny's reign is Ted Koppel's Nightline, a show that couldn't be more opposite of Tonight. Johnny not only changed the way America watched television, he also changed the power center of the television industry; when Tonight turned its California stints into a permanent move to Burbank in 1972, it gave the West Coast more influence, eventually resulting in all operations save the news organizations moving to California.

Time differences naturally mandated that the show be taped, but Johnny always ran the show as if it were being broadcast live; if something went wrong with a bit, a singer flubbed his/her lyrics, an animal didn't cooperate or whatever, it went into the show. And though Carson rarely showed any emotion save that of genial host on the show, there were two memorable times when Johnny made it clear he was not pleased with someone. The first came when Barbra Streisand, notoriously unwilling to make TV appearances, agreed to guest on the show, then pulled out at very nearly the last minute with no real excuse. Johnny made it very clear on the air that night what had happened; he also made it very clear that not only did he consider such behavior unprofessional, but that Streisand would not be booked on the show again. The second instance came when, for the first time in its history, taping for Tonight was halted. John Davidson, a C-list actor and singer who made frequent appearances, experienced some sort of trouble with his sound system. Instead of soldiering on like a trouper, Davidson blew up at the technicians and then stalked off the stage, refusing to continue the show. With no time to replace him, the show had to be canceled and a rerun put in its place. On the next show, Johnny again explained what had happened and again made it clear that such unprofessional behavior had bought Davidson a ban from ever appearing again. And Johnny was nothing if not a man of his word; neither were ever booked on Tonight as long as Carson remained its host.

Johnny Carson's talent at hosting was so great that he made it look easy to do Tonight, a fact which made it difficult for him to get the network to listen when he said he needed more time off. The first salvo came with the show's length; Tonight originally ran an hour-and-three-quarters, from 11:15pm to 1am. When NBC turned a deaf ear to Johnny's pleas to reduce the show's length to ease his workload, he simply stopped showing up for those first 15 minutes; the show was cut to an hour-and-a-half in 1967. The move from an hour-and-a-half to an hour in 1980 was accomplished simply by asking; NBC had learned not to ignore its proverbial goose-that-laid-the-golden egg by then. Johnny also began increasing his vacation time, which became the subject of running jokes but was also vital to keep him in top form. As guest hosts began to sit in for Johnny, both the audience and the television industry discovered that it wasn't as easy as it looked. The vacation jokes began to die off, and Johnny began receiving the respect from his peers that he deserved. This talent was recognized further when Johnny was asked to host the Emmy awards, and later the Oscar awards. To this day, he remains one of the better hosts the Motion Picture Academy has ever had for its telecasts.

But everyone knew it couldn't last forever, no one more so than Johnny himself. He often expressed to those closest to him the desire not to, as Peter Lassally put it during David Letterman's tribute to his mentor, stay too long at the fair. He didn't want to suffer the same fate as his idols Groucho Marx and Jack Benny, or contemporaries such as Bob Hope and George Burns, had suffered; he didn't want to dodder onstage, feeble of body and mind, trying to grasp that last little bit of glory and tarnishing the memory of past greatness in the process. He often requested that his producers tell him when it was time to go, and then remind him of why he should stay away. But in the end, that exquisite sense of timing didn't fail, for it was Johnny who realized the time had come, even if, as whispers have it, he was pushed just a bit.

Most have likely heard by now what was rumored to have happened; no confirmation ever came from any of the players involved, but the whispers remained loud enough and issued from enough places that there does seem to be some credence to the tale. Jay Leno, Johnny's permanent guest host at the time was, according to his agent, thinking about ending his guest-host status and going over to host a show on "another network", one that would compete with Late Night with David Letterman. The agent made it clear that Leno would stay with NBC if he could be given a definite time by which Johnny Carson would retire and hand the reins of Tonight over to Leno. Never mind that Johnny had repeatedly stated he saw Letterman as his heir apparent; Leno's agents convinced the suits at 30 Rock to get him the Tonight Show, and a solid timeline for same, or else Leno was gone. Johnny's contract was coming up for renewal around that time, and for some reason that the suits are probably still trying to figure out, the suggestion was made that Johnny set a definite point, maybe three or five years down the road, when he would step down as host. One can imagine Johnny's reaction to such poor treatment at the hands of the network that his show had at times kept afloat, but he gave the suits what they wanted. On his terms, of course. If they wanted him to set a retirement date, he'd set one: May 22, 1992, about six months out.

The announcement set the entertainment industry abuzz, and was greeted with sadness by Johnny's legion of fans. The months leading up to his departure saw a parade of stars, some of whom had never appeared on the Tonight Show before, lamenting Johnny's departure and wishing him well. The penultimate show was the last one on which Johnny had guests; Robin Williams and Bette Midler had that honor. The final show was about, as Johnny put it, the Tonight Show family; the "guests" were Ed McMahon and Doc Severinsen, and the show was filled with clips, some of which hadn't been seen since they first aired. At the show's end, Johnny bid the audience farewell with a very emotional speech, saying in part, "I am one of the lucky people in the world. I found something that I always wanted to do and I have enjoyed every single minute of it." Johnny also expressed the hope that when he found something else he was interested in and thought the audience might like to see, that we would be as gracious at inviting him into our homes as we had been with Tonight. Holding back the tears, he closed the show with, "I bid you a very heartfelt goodnight."

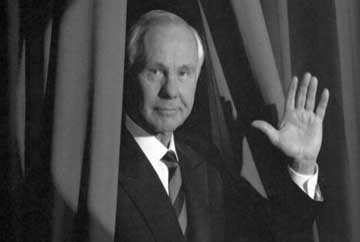

Just as he had not needed his friends and associates to tell him when it was time to leave the stage, he also didn't need them to remind him to remain off it. He made only a very few appearances after leaving the Tonight Show, the final one in 1994, on David Letterman's CBS show. Letterman was doing a series of shows in California, and each night, Larry "Bud" Melman, billed as different celebrities, had brought Dave the Top Ten list. On the final night, Melman came out as "Johnny Carson" and gave Dave the list. After Dave declared it wasn't the correct list, he called for "Johnny" to bring out the real one. At that cue, Paul Schaffer swung into the familiar theme, and Johnny Carson walked out from behind the curtain, looking very much as he had when he'd left the stage two years before. Johnny took his place behind Letterman's desk to thunderous applause, and just as the audience adulation began to die down, it looked as though Johnny was about to say something. Instead, he got up from the desk, waved to the audience, and disappeared behind the curtains. It was later reported Johnny had a joke to do, but had laryngitis and was una