Book vs. Movie: A Home at the End of the World

By Kim Hollis

August 30, 2004

If movies like Freddy vs. Jason, Godzilla vs. Megalon, Alien vs. Predator, Godzilla vs. Mothra, Kramer vs. Kramer, Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah, Ecks vs. Sever, Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla and King Kong vs. Godzilla have taught us nothing else, it's that everything is somehow better in battle format. We here at BOP recognize this fact, but at the same time realize that our breed of super-smart readers sometimes yearns for a touch of the intellectual at the same time. And since Hollywood has a certain obsession with turning literature of all types into big screen features, we're afforded the perfect opportunity to set up grudge matches galore.

And so, whenever the Tinsel Town hotshots decide that it's a great idea to turn the little-known Herman Melville classic Redburn into a theatrical event film, we'll be there. Whether the results are triumphant (see: The Lord of the Rings trilogy) or tragic (i.e. The Scarlett Letter), we'll take it upon ourselves to give you the verdict and spark the discussion.

A Home at the End of the World

Based on the Michael Cunningham (The Hours) novel by the same name, A Home at the End of the World explores unexpected families in various iterations as well as notions of love, whether it be romantic or the more sublime agape. Since Cunningham adapted the book to screenplay form himself, would it retain the marvelous character construction and the intelligent examination of what defines kinship?

The Book

Cunningham's novel is, at its heart, a deep character study of four individuals whose lives interconnect and separate over the course of three decades. The story switches back and forth from the first person viewpoint of one person to another. "Bobby" opens the story with a recounting of some of the events of his youth, giving readers a clue to the psychological background that helps comprise his unique personality. Bobby is a singular character in modern literature; his capacity for love and ability to adapt to his surroundings are exceptional. At times he appears to be a wide-eyed naïf, while at others he intuitively comprehends precisely what the people around him need for emotional comfort.

Next, we meet Jonathan, a precise and somewhat withdrawn young man. He and Bobby meet as teenagers when they both attend the same school. The boys become fast friends thanks to a shared appreciation of music and marijuana. The relationship develops to a point where they are lovers of a sort, though not by the strictest terms of the definition. Despite the fact that Jonathan is in love with Bobby, Bobby's capacity for love is so all-encompassing that he can hardly comprehend the notion of loving only one person. That's not to say that he sees other people - he spends almost all of his time in Jonathan's house due to a shattered family life - but rather that he experiences things differently than a typical person might.

Alice, Jonathan's mother, also has her own commentary to offer. She may actually be the most fascinating character in the book, as the reader is able to watch her react to the changes her son experiences and wonder at her own contribution to his nature. Her evolution as the mother of a young homosexual man is believably and realistically depicted.

The years pass, and Jonathan eventually moves out of his family's Cleveland home to attend college in New York City. Bobby stays behind and rents a room from Jonathan's parents, where he lives a contented existence as a baker. More time flies by, and Jonathan's father Ned becomes increasingly ill with emphysema. Under doctor's recommendations, he and Alice move to Arizona, leaving Bobby as a man without a home. He and Jonathan are now in their mid-20s.

Jonathan agrees to let Bobby move in with him and his roommate in their bohemian apartment in New York. At this point, we meet Claire, who lives with Jonathan. She's about a decade older than Jonathan and Bobby, and extremely individualistic. When Bobby arrives on the scene, he learns that she and Jonathan are considering having a child together. When he wonders aloud that they couldn't possibly be in love, her response is that no parents ever really are.

Naturally, matters become complicated as Jonathan attempts to keep his own separate life. He wants that time away from Bobby and Claire where he pursues his interests by dating the men he chooses and working as a restaurant critic for a local indie newspaper. Because Bobby can hardly bear to spend time alone, the bulk of his time is spent with Claire. It's not long before they've fallen in love - in a fashion. When Claire becomes pregnant, the trio finally comes to a decision that they will attempt to have their own distinctive family, where all three will play a part in the child's upbringing. To do so, they will move to a small farmhouse near Woodstock, a place of mystery and wonder for Bobby.

What the book does particularly well is to dissect notions of family. What one might consider a "normal" family - i.e. Jonathan and his parents - is revealed to be as dysfunctional as any clan ever illustrated in literature. Alice is a deeply unhappy woman, though it's really not due to any particular fault of her husband or child so much as something intrinsic to her alone. There is no condemnation of anyone, though. The relationships are what they are. That the book manages not to be preachy even as it tackles some weighty social issues - including homosexuality, AIDS and unconventional families - is truly to its credit.

The Movie

Though Cunningham did adapt the screenplay of his own novel, the film does diverge quite a bit from the slowly developing story of the novel. Many of his changes were clearly made with an eye to keeping the film moving at a more brisk pace, though some also must have been done because the deep level of character development simply wasn't possible in the time available in a movie.

In the film, the primary characters are mostly well cast. Dallas Roberts is exemplary as Jonathan, down to mannerisms, appearance and the darkness intrinsic to the role. Robin Wright Penn is the quirky Claire, and she does a marvelous job of portraying the character's complex motivations. Sissy Spacek has a fairly limited role as Alice, and she does a fine job with the character as she is written. I should note, though, that the Alice of the film is substantially more superficial than the Alice of the book. That's a failing, too, because the movie would really have been more compelling if she had been more complicated and realistic.

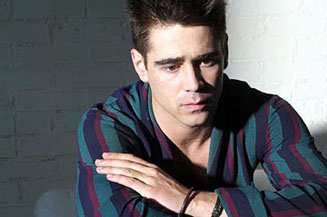

The movie's biggest flaw, though, is the casting of Colin Farrell as Bobby. On one hand, he's too pretty to play the role, but even worse, his portrayal of the character is nothing short of aggravating. It's frequently difficult to tell if he's just trying to interpret Bobby as a bewildered, stupid, naïve, or some freaky combination of the three.

The Verdict

My recommendation on this one is fairly straightforward. The book offers a much deeper, compelling experience than the film. From Farrell's too-simplistic portrayal of Bobby to the lack of significant character development in the cases of several other characters, it's just much, much more rewarding to watch the lives unfold on the page. And though Farrell's performance bothered me, perhaps my biggest disappointment with the film is the fact that Alice is simplified and made so vanilla. Despite the fact that the character is not particularly likeable or sympathetic in the novel, it's preferable to see those layers of gray. The film accepts simple black and white depictions for both its questions and answers.

|

|

|

|