In Passing, 2006

Part I

By Stephanie Star Smith

January 15, 2007

|

Each year at the Academy Awards, Hollywood takes a few moments to honor those who have joined the Choir Invisible during the previous year. Each year sees a number of people barely recognized even by their industry peers, much less the viewing audience, along with a smaller percentage of more widely-renowned names (and the inevitable few "I didn't know he/she died"). As the calendar year draws to a close, we here at BOP would like to acknowledge some of Hollywood's brightest luminaries who shuffled off their mortal coils in 2006 with a look back at the reasons why though they may be gone, they will certainly not be soon forgotten.

|

|

|

Shelley Winters

Shelley Winters

Shelley Winters was, by all accounts, one gutsy broad, and she made her name in Hollywood by playing parts not that far from her real character. Born Shirley Schrift in Illinois, Shelley became interested in acting in high school, where she performed in as many school plays as she could be cast in. From there, it was a short graduation, so to speak, to the vaudeville circuit, one of the many ways she made her living whilst honing her craft in acting classes. At various times in her early years, Shelley was a model, clerk at Woolworth's, and a dancer in night clubs, all in service of her ambition to become an actress. First noticed by director George Cukor during the nationwide publicity-stunt/search for the part of Scarlett O'Hara in Gone with the Wind, she took to heart Cukor's advice to continue her acting lessons, and gradually advanced her craft to the point where she was getting steady work in summer stock, which is where she began using a stage name she created by combining her mother's maiden name with that of her favorite poet, becoming Shelley Winter. The S came later, courtesy of a typo on the Universal call sheet for A Double Life, and Shelley Winters was born.

It wasn't long before the siren song of Hollywood caught young Winters' attention, and she headed out West, as so many other young women have before and since, to make a bid for silver screen stardom. But the going wasn't easy, even with the benefit of the studio system; being neither drop-dead gorgeous nor an obvious choice for character roles, Winters toiled for many years in bit parts and uncredited roles in a string of B movies until her first big break came, courtesy of the director who had counseled her to take acting lessons years before, George Cukor. She won rave reviews for her role as a waitress-cum-party girl who becomes the victim of a serial killer in A Double Life, and capped her new-found stardom by returning to Broadway and assuming the role of Ado Annie in Oklahoma!, which also brought her acclaim, and Winters would split her time between the stage and the big and little screens for the rest of her career. In Hollywood, a series of working-class, earthy-type roles followed her breakout in A Double Life, and she became a film staple as the down-on-her-luck, best-friend-of-the-lead who often met a bad end. The quintessential role of this portion of her career was her turn as the wrong-side-of-the-tracks, pregnant ex-girlfriend of Montgomery Clift's social-climber in A Place in the Sun, which garnered Winters her first Oscar nomination. Instead of providing the boost to her career that one would expect, however, it led to Winters taking a series of unmemorable, blowsy-blonde roles in even-less-memorable B pictures, an unwise move that nearly led to the demise of her career, but a stint with Lee Strasberg at the Actor's Studio not only provided her the boost she needed to reclaim the meatier roles she desired, but instilled in her a life-long belief in the Method school of acting. She remained an honored member of the Actor's Studio for many years, and often taught classes for some of the up-and-coming talent.

Winters' career renaissance began on the Broadway stage, where she restored her reputation as a serious actress with stellar performances in A Hatful of Rain and A Streetcar Named Desire. Back in Hollywood, she won acclaim playing Robert Mitchum's unfortunate wife in Night of the Hunter, and received her first Academy Award as Mrs Van Daan in The Diary of Anne Frank, which she later donated to the Anne Frank Museum. There followed a series of high-profile supporting roles in major films, culminating in a second Oscar for her work as the prostitute mother in A Patch of Blue. As she aged, she wisely chose more character-type roles, playing a number of well-meaning but interfering mothers before securing her fourth Oscar nod as the champion swimmer who helps save Gene Hackman in The Poseidon Adventure. Winters also returned to Broadway several times, securing another signature role as the mother of the Marx Brothers in Minnie's Boys. As the '70s wore on, Winters became a staple of episodic television and the talk-show circuit, where she was known for her bawdy wit and her salacious tales of the behind-the-scenes Hollywood. It was during this period that she wrote two best-selling autobiographies, which detailed a life as colorful and scandalous as any of her film roles. She also became an outspoken feminist and political activist, using her fame - as so many have done before and since - to champion causes that were important to her.

Failing health in Shelley Winters' later years led her to cut back on performing, although she created one more memorable mother when she appeared on Rosanne Barr's eponymous show as the fictional Roseanne's outspoken momma. By the turn of the 21st century, however, Winters was largely confined to a wheelchair, and a heart attack in 2005 led to the decline that culminated on January 14th, when she left this vale of tears shortly after marrying her long-time companion and fourth husband. But she left behind a film legacy of colorful, vivacious, earthy characters who always loved perhaps not wisely but too well, much like the woman who created them.

|

|

|

Moira Shearer

Moira Shearer

Moira Shearer never wanted to be an actress. Born in Scotland to a civil engineer who later moved the family to what was then Northern Rhodesia, she grew to love the dancing lessons her mother pushed her into, and trained to become a prima ballerina. But it was exactly this talent that made her a Hollywood name with her first film, The Red Shoes, the story of a young woman who literally sells her soul for a pair of red ballet shoes and the stardom they promise. And though she only made a handful of films after her debut, her flame-red hair and her balletic grace kept her profile high in a town that usually only judges one by the work done recently. Shearer always returned to the stage that she loved, continuing to dance as long as her body allowed, and then turning to straight acting when at last injuries and ill health halted her ballet career.

Starting out as a member of the corps de ballet with the International Ballet and later with the Sadler's Wells Ballet troops, Shearer's first starring role was in Sleeping Beauty, performed at the Royal Opera House in Covent Gardens. She followed her debut as a prima ballerina with a variety of leads in both classic and new ballets until Hollywood came calling in 1948. After she completed filming on The Red Shoes, she returned to her first love, but said in later years that her peers never really trusted her after she became a film star. Shearer holds the distinction of turning down requests by two of Hollywood's most legendary dancers, Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly, preferring the legitimate stage to dancing in Royal Wedding opposite Astaire or Brigadoon opposite Kelly. And though she moved to dramatic parts once her ballet days were over, she never considered herself an actress; she would often turn down plum parts other actresses would kill to be offered because she thought it ridiculous for someone trained as a dancer to take on such roles. It was perhaps this very reluctance that allowed her to be held in such high regard by the notoriously fickle Hollywood crowd, since it kept her from making any horrendously bad films and left behind instead a stellar reputation. In her later years, Shearer toured the US, lecturing on the history of dance; she also authored two books, one on the legendary ballet dancer and choreographer George Balanchine, and one on the early-20th century actress Ellen Terry. She also served on the boards of the Scottish Arts Council and the BBC General Advisory Council. Never one to seek the spotlight, she had faded from the public eye by the time she pirouetted off this earthly stage on January 31st, but her vibrant dancing, and her beautiful mane of red hair, continue to live on in celluloid.

|

|

|

Peter Benchley

Peter Benchley

Just as Robert Bloch helped Alfred Hitchcock scare people out of taking showers in roadside motels, so did Peter Benchley help Steven Spielberg scare people out of swimming in the ocean with Jaws. But as is often so with artists who hit it big on their first try, Benchley never captured that lightning-in-a-bottle again, although he was by no means unsuccessful after it was published.

Born to a literary family - his grandfather, Robert Benchley, was one of the founders of the famed Algonquin Round Table - Benchley worked as a columnist for the Washington Post and an editor at Newsweek before becoming a speechwriter for President Lyndon Johnson. He was inspired to write Jaws after reading a story about a fisherman who caught a 4,550-pound great white shark off the coast of Long Island, and he got his chance at getting it published when Doubleday editor Tom Congdon, having been impressed with Benchley's newspapers articles, invited him to lunch with the idea of publishing some non-fiction books. Congdon wasn't terribly impressed with any of the ideas Benchley pitched for non-fiction, but he was intrigued with the tale of a great white shark terrorizing a small Massachusetts resort town, and gave Benchley a $1,000 advance to write a treatment. Congdon found the 100-page outline sufficiently stirring and commissioned a complete novel, although it went through several rewrites before being published, as the good folks running Doubleday didn't care much for the tone.

Jaws was published in 1974, and was an immediate success, spending an impressive 44 weeks on the New York Times best-sellers list. Although many critics found the characters unsympathetic - Steven Spielberg often said he was rooting for the shark to win - the public loved it, which was all Universal Studios needed to greenlight a movie of the novel, directed by Spielberg. Benchley wrote the script, along with Carl Gottlieb and an uncredited pair of writer, Howard Sackler and John Milius (the latter two provided the first draft of the chilling USS Indianapolis speech), and Jaws the film was released in 1975. There's an interesting piece of trivia connected to the release of Jaws. Back before it hit theatres, studios considered summer to be a dead zone movie-wise; after all, when the weather is nice, people tend to want to be outside. But Spielberg was convinced that given a sufficiently entertaining film, audiences would make time to go to the movies, so backed by an extensive TV ad campaign, Universal agreed to release Jaws smack-dab in the middle of summer (although probably not without some trepidation). As everyone now knows, Spielberg was right; Jaws became the highest-grossing film to date, and along with Star Wars two years later, established summer as the blockbuster event-film season we know today.

After the success of Jaws, Benchley again turned to the sea for his next novel, The Deep, a tale of a honeymooning couple who find sunken Spanish treasure and morphine whilst diving off the Bermuda coast, a discovery that puts them on the hit list of a local drug syndicate. Benchley again found success, albeit not as great as with Jaws, and the film version of The Deep - for which Benchley also wrote the script, along with more seasoned help - followed suit, though it still managed to be the second highest-grossing the year it was released (it was beat out by the aforementioned Star Wars). Benchley would continue to write tales of the sea and the dangers that could be found within it for several more years, including The Island - which was made into a highly unsuccessful film - and Beast, about a giant squid, which became a somewhat-successful TV movie. Benchley also began to visit other themes, including a semi-autobiographical tale, Rummies, and Q Clearance, based on his experiences as one of President Johnson's speechwriters.

In later years, Benchley became an ardent champion of the sea and the life within it, working to educate the public as to the damage humankind has done to the marine environment, and spearheading efforts to repair some of the harm done over the many centuries. He also revisited the great white shark in the novel White Shark, about a Nazi-created shark/human hybrid. Critics didn't find this fare very palatable, but the novel still made it onto the small screen, retitled Creature.

By the time Peter Benchley's story reached its end on February 11th, he had been out of the film and TV scripting business for some time; still, when summer comes around and people head towards the beach, the frisson of fear they feel at what might be awaiting them in the billowing waves is a permanent memorial to the man who made us wonder if it's ever really safe to go back in the ocean.

|

|

|

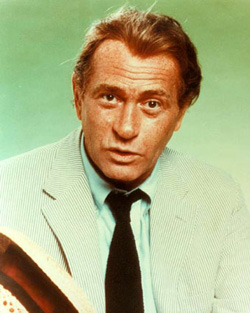

Don Knotts

Don Knotts

Say the name "Don Knotts", and instantly an image is conjured: A thin, nervous man whose limbs seem not to be under his control and who looks for all the world like he might bolt out of sight at any moment. That persona, perfected during his years as part of Steve Allen's repertory company during his stint hosting The Tonight Show, served as a star-making springboard for a long and varied film and television career.

But the real Don Knotts wasn't really much like his professional persona. Born Jesse Donald Knotts in West Virginia, the youngest of four children grew up with a love of performing, beginning as a ventriloquist in high school. With his dummy, Danny, he became proficient enough to earn paying gigs at parties around his hometown. Deciding to pursue a career in show business, Knotts moved to New York for a brief go at making it, but after being told he had no future in acting, he returned home, enrolled in West Virginia University and took a job on the side plucking feathers off chickens. But Fate took a hand in his life path in the form of World War II; when Knotts enlisted, he was assigned to Special Services, which was responsible for entertaining the troops. In addition to serving with distinction - he received several medals - his Army service was where Knotts decided to move from ventriloquism to straight comedy, and a nascent star was born.

After his discharge from the Army, Knotts decided to complete his education West Virginia, receiving a BA in Theatre. After graduation and marrying his first wife, Knotts moved the family to New York and tried once more to make a go of it in show business career. His second try was more successful, thanks to the connections he made during his Special Services stint. He was soon doing stints on Broadway and on radio; he was also one of the early performers to venture into the new medium of television, with a recurring role on the soap Search for Tomorrow. His next brush with the hand of Fate came courtesy of winning a small role in the Broadway production No Time for Sergeants, where he met long-time friend and mentor Andy Griffith; Griffith would continue to play a large part in Knotts' career for many years to come.

After reprising his role, along with Griffith, in the movie version of No Time for Sergeants, Knotts became part of the company of players who helped Steve Allen create the first incarnation of The Tonight Show. This is where he perfected his persona of the "Nervous Guy": Shaking and rabbit-shy, with a deer-in-the-headlights look that audiences sympathized with whilst laughing. When Steve Allen left Tonight and moved out to Hollywood, Knotts followed, continuing to appear on the show until his friend Andy Griffith called to offer him a part in Griffith's eponymous show. His turn as Deputy Barney Fife made his name in Hollywood, in addition to winning him five Emmys for Best Supporting Actor in a Comedy, and he was soon being courted by the studios to bring his persona to the big screen. Knotts cut back appearances on the Andy Griffith Show to appear in a series of big-budget movies, scoring almost instantly with the combination live-action and animated film The Incredible Mr Limpett. A contract with Universal Studios soon followed, and Knotts employed his Nervous Man/Big Talker character in a number of successful films, including The Reluctant Astronaut, The Shakiest Gun in the West, and The Ghost and Mr Chicken. His name established on both the silver screen and the small screen, Knotts continued to work in both mediums for most of the '60s.

As the '70s dawned, however, Knotts saw his big-film career on the wane, so he filled his time by returning to the stage and making the occasional guest appearances on TV, until Disney came calling mid-decade, pairing him with Tim Conway for a series of slapstick comedies that brought Knotts' brand of levity to a new generation. Knotts would move between TV and movies for the rest of his career, with high points including adding his unique voice to a number of animated films, and taking over as the would-be swinger landlord on Three's Company when the show's original landlord couple was spun off into their own comedy, appropriately named The Ropers. When Three's Company was canceled, Knotts returned to doing guest appearances in between film roles, and reunited with his old pal Andy Griffith on the latter's second series, Matlock, where he had a recurring role as the nosy neighbor Les Calhoun.

Knotts continued working right up until the Ferryman came calling on February 24th, doing stage plays and making the occasional TV appearance, but mostly doing voice work in animated films; his last big-screen appearance was voicing the role of Mayor Turkey Lurkey in the computer-animated film Chicken Little, and he provided the voice of Wormie for the straight-to-video series Hermie and Friends. Not a bad resume for a guy told he had no future in acting.

|

|

|

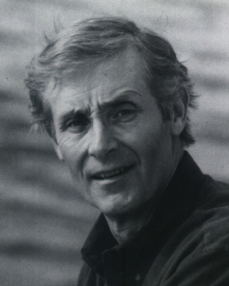

Darren McGavin

Darren McGavin

It's not often that an actor has the chance to create a role that resonates with the public, rarer still when the chance to create two such roles comes along. Darren McGavin managed just such a feat, with Carl Kolchak, the cynical reporter who kept uncovering paranormal phenomena; and as the irascible, turkey-loving father in the classic film A Christmas Story. But McGavin had a wide range of roles over a career that spanned five decades on stage and in films and television.

McGavin received his acting training in New York, studying at both the Neighborhood Playhouse with famed acting teacher Sandy Meisner, and prestigious Actor's Studio. His start in films saw him playing a number of minor roles before landing his breakthrough role as a drug pusher in The Man with the Golden Arm, directed by Otto Preminger. He followed this up with a key role in The Court Martial of Billy Mitchell, also directed by Preminger, establishing himself as a versatile actor who could handle meaty roles. His good looks also helped, landing him the part of Mike Hammer in a one-off TV show of the same name. His career firmly established, McGavin worked steadily throughout the remainder of his life, switching easily between the big screen, the small screen and the stage. Along the way, he appeared in many classics, including the plays Death of a Salesman and The King & I; the movies The Delicate Delinquent and Because James; and numerous TV guest appearances, mini series and TV movies, most notably as General Patton in the TV mini Ike, and a key role in The Martian Chronicles mini-series. McGavin also showed a deft hand for comedy, with movie turns in Hot Lead and Cold Feet and No Deposit, No Return and on TV as the father of Candace Bergen's character on Murphy Brown.

But it was his role as Carl Kolchak that made him a cult favorite, and although the series Kolchak: The Night Stalker, which followed two highly-successful made-for-TV movies, lasted only one season, it gained a cult following. It is even said to have inspired Chris Carter to create the cult hit The X-Files, on which McGavin had a recurring role as Agent Arthur Dale. Both series continue in syndication across the world to this day.

Darren McGavin also helped in the creation of another classic, the perennial holiday film A Christmas Story, in which he played the father of young Ralphie. McGavin is widely credited with getting the film made; he believed so much in the project that he agreed to take a cut in his usual salary and even helped to secure a distribution deal. The movie didn't make a huge splash at the box office, but it has become a Christmas staple, with TNT showing it back-to-back-to-back for 24 hours straight on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day.

As with many aging stars, McGavin faded from view at the dawn of the new millennium, making only one appearance - through the magic of a computer - in the ill-conceived and -fated remake of The Night Stalker, where a shot of him from as the original Kolchak was composited into the background of a newsroom scene. Fortunately, this misbegotten project mercifully didn't even last a season, thus avoiding the possibility of tarnishing both the original portrayer and series. But when Darren McGavin shuffled off his mortal coil on February 25th, he had left behind a body of work covering all manner of characters and genres, and two memorable parts in Carl Kolchak and Ralphie's dad.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|