Movie Review: Finding Dory

By Ben Gruchow

June 23, 2016

BoxOfficeProphets.com

DeGeneres and Brooks both return for Finding Dory (Hayden Rolence plays Nemo, instead of Alexander Gould), and the conflict and situation that sets up this sequel’s storyline with Dory is layered and nuanced in a way that the first movie mostly avoided: absent the quest storyline, the question mark of living day-to-day with a persistent disability that goes on the offensive of the same part of you that tries to understand it, and the effect it has on family and friends. The movie doesn’t exactly background this, either. Right from the opening scene, featuring a young Dory’s parents balancing playtime with the knowledge that letting her out of their sight possibly equivocates losing her forever, the rumination on these story elements is etched deeply into the fabric of the film. This sets up the first of two or three brutally evocative passages in the film; young Dory gets separated from her parents by unexplained means, goes to find them, and we see her reach out to others again and again with the same question - even after she forgets who or what it is she’s looking for. This is disquieting, poignant material, and it’s as strong a curtain-raiser as we could hope for.

These elements are introduced, explored a little bit, and then left to their own devices; we are yoked back gently into the world of a sequel to a blockbuster film. This is never more apparent than in the graceless and arbitrary fashion in which the film transitions from the opening with young Dory into a (very) brief recap of the introduction scene between Dory and Marlin from Nemo, and then flashes forward a year to the era of the story proper. This last is done as a tossed-off kind of screen fade, as Dory leads Marlin into the distance. It’s not true that Finding Dory never whiffs to varying degrees on finding the proper rhythm or tone, but none are quite as arbitrary, nor as rude in their awakening: it’s time for the intrinsic character development to come to an end, and the purpose of a movie titled “Finding Dory” to begin asserting itself.

That purpose takes the form of another quest, although one different in execution and duration. This one is more of a mystery: during the course of what is more or less a normal day, Dory finds herself suddenly remembering flashes of memories, most of them about her parents. One memory in particular sticks out, a location (similar to her remembrance of Wallabe Way in Sydney); bent on finding her family again, and with Marlin and Nemo in tow, she sets off to do so.

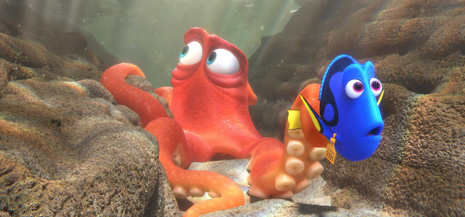

The quest on its own occupies a surprisingly short stretch of the film, and much of the major developments and character bits happen after they reach their destination: the Marine Life Institute in southern California. Through a brief series of mishaps, Dory ends up inside the facility, and we’re introduced to a new cast of supporting characters: Hank (Ed O’ Neill), a red octopus with a missing tentacle (“You’re more like a septopus,” says Dory upon meeting him); the whale shark Destiny (Kaitlin Olson); and beluga Bailey (Ty Burrell) get the most screentime, but the best of them is a pair of sea lions voiced by Idris Elba and Dominic West. They are the functional equivalent of Bruce the shark from the first film: scene-stealers within the first line or two of dialogue.

The new stuff here is slight but enjoyable, and it looks expectedly great; I particularly liked Hank’s design and animation, flexible and slippery without being off-putting, and the use of memory to unlock the story developments gives us enough divergence from the first film for Finding Dory to avoid feeling like a retread, for the most part. Another wise decision in this regard was compressing the travel part of the narrative and allowing the sequences at the Marine Life Institute in the back half of the film much more room to breathe as narrative. And there’s a moment of startling impact after a major revelation; we are given a point-of-view shot that travels with us from an aquarium down to the floor, down into a drain, and out into open water.

This moment and a few others show us that Stanton is not afraid to use the framing of an animated family film to communicate complicated feelings of isolation and fear, and it’s this type of willingness to “go big” with its thematic sophistication that Pixar does better than anyone else. I wish there were more of it this time. The riskier stuff is the exception in this movie, and what we’re mostly given are scenes set at a decidedly lower temperature, like a reappearance by the tortoises from the first film (and I’d like to mention that the manner in which we’re reintroduced strains credulity, even on the movie’s own terms, and that may be why we’re given no explanation at all as far as how it happened).

Nowhere is this risk aversion made more evident, though, than in the way Marlin and Nemo are shoehorned into a story that has no use for them; apart from a brief interlude that employs water fountains in an amusing way, the two characters (who are separated from Dory once they arrive at the Institute) are mostly reduced to restating story beats or rehashing character beats. Marlin is particularly egregious; he seems to have regressed fully into the over-cautious parent he was in the first film, which has the undesirable effect of negating much of his character development. Nemo, meanwhile, mostly just sulks around and expresses resentment. Neither of them are actively bad; they’re just flagrantly unnecessary. The artificiality of their contribution to the proceedings is emphasized in their role in the movie’s climax; all of the character beats and resolutions have been worked out by this point, and what’s left is mostly just movement and color.

It’s solidly entertaining movement and color in the moment, to be sure, and a slight Pixar movie is almost by default and design going to have more to offer its audience than most of its animated brethren. Were this exact film produced by any rival studio, it’d be a lot harder to criticize in any kind of context. Finding Dory is not a classic, and its lightweight construction contributes to a quick evaporation process that begins once the credits roll, but it’s likable enough on those grounds.

Note: Pixar generally screens a short film before each of their features; the short attached to this one is called Piper. It’s a six-minute set piece on a beach featuring a baby sandpiper (among many adults), and it’s a marvel: easily some of the most accomplished naturalistic animation and cinematography the studio has ever put their name to, and a truly wonderful instance of nonverbal, minute, and wholly effective performance. Your mileage may vary on Finding Dory, but Piper is worth the ticket price to see on a big screen on its own.