Viking Night: The Man Who Fell to Earth

By Bruce Hall

October 13, 2015

BoxOfficeProphets.com

I guess what I’m saying is, David Bowie is probably an alien.

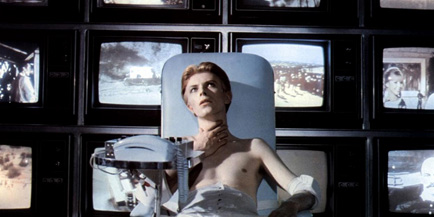

Little wonder, then, that he was tapped for The Man Who Fell to Earth, Nicolas Roeg’s avant-garde revision of the novel bearing the same name. The finished product is something of an enigma, taking only a handful of concepts from the novel and attempting to adapt them into something that’s presumably relatable to the world of 1976. It’s a sprawling, ambitious, confusing and at times, downright pretentious film that covers a lot of ground. But it does so as if running serpentine across a minefield under heavy sniper fire. It’s a desperately sad story, rife with symbolism, social commentary and subtle humor - but if you can make sense of it all by the end, you’re a hell of a lot smarter than I am.

It’s perplexing right from the start, as an alien spacecraft crash lands in the American Southwest, and its lone occupant wanders into a thrift store to sell his only possession, a gold ring. He identifies himself as Thomas Jerome Newton (Bowie), a British citizen with a New Wave haircut 10 years ahead of its time. He eagerly accepts 20 dollars for the ring, but minutes later, sitting by the side of the road somehow produces a roll of hundreds from his pocket. Did he rob the place? Did he spend the day at an Indian casino? Your guess is as good as mine, because this is only the first of many peculiar inconsistencies that never get explained.

What we do know is that Newton has a thing for water, to the point that he’s willing to drink it right out of the kind of nasty looking creek you and I wouldn’t even stop to pee in. What's the deal with that, you say? Hold on. We'll get to that.

Eventually Newton makes his way to Manhattan, which is probably not very hard when you can apparently fart hundred dollar bills. He randomly drops by the apartment of prominent patent lawyer Oliver Farnsworth (Buck Henry) with a portfolio full of world-changing technology and offers Farnsworth a cut if he'd be willing to go into business with a complete stranger. After looking past the initial shock of David Bowie standing in his living room with the blueprints for the Flux Capacitor, Farnsworth is able to see the dollar signs and agrees to the deal. If you're unclear as to the significance of this, imagine it's 1977 and Steve Jobs falls out of the tree in your front yard with an iPad under his arm and says "Do you think this might be important?"

So, a few years later, Newton and (name) are the top of the org chart at World Enterprises, the largest and most powerful company in the history of ever. And the more money they make, the more reclusive Newton becomes. Eventually, he relocates the company to New Mexico, where he originally landed, and takes up with a wide-eyed local named Mary Lou (Candy Clark). She introduces him to modern conveniences such as television, alcohol, and oral sex, only the first two of which he becomes hopelessly addicted to (he is an alien, after all). This begins to interfere with Newton’s mission, clouding his judgment and causing him to become withdrawn and emotionally unstable. As he inches closer to his goal, circumstances intervene and his choices catch up with him, pushing it ever farther out of reach.

All of this might be sad, except for a few things.

First of all, remember Newton’s affinity for water? Well, it turns out the point of his being here is to use his superior alien intellect to amass great wealth so he can build a giant spaceship and ferry water back to his stricken planet. It’s kind of a stupid plan, because anyone smart enough to build an interplanetary starship must know that on the way to Earth he flew right past enough ice to top off a dozen planets with watery goodness. It’s just floating around out there minding its own business. Kevin Costner and Dennis Hopper could spend decades chasing each other around on jet skis and never see land. Newton’s solution to this problem is the equivalent of taking a boat to China for Chinese food instead of just picking up a phone and ordering out.

But that’s just nitpicking. Obviously, the point of all this is not to be scientifically accurate, but to illustrate an important allegorical point of some kind, but it’s incredibly difficult to tell what that’s supposed to be. The themes explored in the novel are more in line with the Cold War paranoia that was fashionable in the early ‘60s, while the film feels more like a vague indictment of consumerism and a half-hearted meditation on morality and personal choice. But the story jumps forward in time on several occasions without warning, making it unclear how much time has passed. Are they in the ‘80s now? The ‘90s? Everyone looks older, but it still looks like they’re in 1976.

At various times, Newton experiences visions of his family back on his home world. He also seems to have an ability to see into the past, or to exist in multiple time frames. Occasionally, he appears to have some sort of mind reading ability. But none of these experiences ever amount to anything and it’s never clear what - if anything - it all means. At one point, World Enterprises attracts the attention of what seems to be the government, who try to intimidate Farnsworth with threats so mysteriously cryptic it’s almost hard to take them seriously, let alone fully understand what the problem is. The story digresses at a couple of points to focus on Farnsworth’s personal life, but it doesn’t seem to have any relevance to the overall plot. And we spend a little too much time with Peters (Bernie Casey), a government agent who lives like a mafia Don and openly wonders whether or not his actions are morally justified.

I do too, because I have no idea who he is, what he’s doing, or why we have to spend 10 minutes watching him making out with his hot wife and putting his kids to bed right in the middle of the film. I could go on for another thousand words about how frustrating this movie is, but I think you get the idea. But what’s more important is that while yes I was perplexed, yes I was confused and yes, at times I was praying for it to end, I was never at any point patently uninterested. That sounds like faint praise because it is. But The Man Who Fell to Earth is such an ambitious and thoroughly avant-garde undertaking that it’s hard for me to fault it for swinging so hard at the ball. They don’t make movies like this anymore, and while in some ways that’s a good thing, it’s also the reason most science fiction movies these days feel like something you’ve already seen a hundred times before.

David Bowie was an ideal choice for the lead here, because if you could turn the man himself into a two-hour film, this is about what you’d get. It’s maddening, moving, haunting, laborious, and fascinating - and whether you love it or hate it or just end up scratching your head like I did, you’ll still be thinking about it a week later.

I guess what I’m saying is, David Bowie is probably an alien.