Movie Review: American Ultra

By Ben Gruchow

August 25, 2015

BoxOfficeProphets.com

The story is a total mess: motivations and incidents are assigned more or less randomly, and the entirety of any given character’s inner monologue is structured around whether or not a good gag can be pulled out of the moment. American Ultra reminds me a lot of 2006’s Slither in how fundamentally flawed it is as a narrative; in both films, the roster of characters can and do resemble actual people - and can draw what resembles coherent philosophy out of them - while pretty clearly existing only to serve the gag.

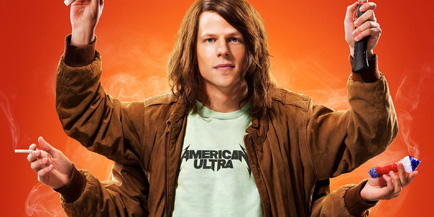

The gag here, of course, being a scruffy and laconic take on the Bourne storyline, where an average guy turns out to be a sleeper agent, trained in whatever lethal skill the screenplay requires of him at any given time. This guy is Mike (Jesse Eisenberg). The other principal player is Phoebe (Kristen Stewart), who plays his girlfriend as a collection of pauses and gentle corrections. I will not identify the party on the other end of the situation; I have a feeling the movie cares less than I do about who’s pulling the strings. There is Connie Britton, and she is mostly good; there is someone else, and we’ll come back to him.

One of the other ways that the movie reminds me of Slither is in its tonal lightness, mashed together with a B-movie anything-goes absurdity. That movie understood how a grossly deformed monster knocking over a table lamp could work as a gag if you framed and timed it just so; American Ultra is a movie that understands how a formidable woman in sunglasses can work as a gag if you frame and time it just so. The key that both movies exhibit is that these gags work without sacrificing their innate horror (in Slither’s case) or their innate tension (here). Both movies have the courage of their convictions, and stick with their internal logic and mood more or less all the way to the end.

American Ultra gets more points for the way it sets up its pieces; there is a methodical and deliberate pace to the early scenes, aided greatly by a precise sense of timing on the part of editing team Andrew Marcus and Bill Pankow (Pankow is a frequent collaborator of Brian de Palma; I have no idea what he’s doing here, but his expertise and sensibilities show in a big way, and half the reason American Ultra makes it so close to success is because of what he brings to the table).

They sew together images shot with clarity and depth by Michael Bonvillain (he worked on Eisenberg’s 2009 comedy Zombieland, which was another movie that understood the concept that silliness and gravity were not mutually exclusive, and was also far better-looking than it needed to be), working off of a fairly whacked-out screenplay by Chronicle’s Max Landis, and what results are scenes - especially in the early going - that have an unusual amount of texture to them. It’s not at all meaty enough to sustain a movie that would be dedicated to it, but it’s more detailed about depicting complicated and partially broken relationships, and the anxiety of suspecting that you’re stalled-out in life without knowing why, than it ever really needed to be.

Eisenberg and Stewart are both perfect for these types of roles, with the former managing to project a suspicion of inquisitive intelligence under a fairly constant veneer of dimwitted amiability. That is not an easy task, and Mike is not a particularly complete character (later in the film, when crucial bits of information begin to trickle out, we realize that we have very little context for it other than what we’re strictly being told), but Eisenberg takes these spare parts and creates a believable person.

Stewart is his equal. We’ve known since Panic Room that the actress can sell a range of elevated emotions; the Twilight series shuttled her into blank window dressing for four or five years, but she hasn’t lost her touch. And with Britton, the movie gives us something we see far too little of: a warm and authoritative middle-aged female character, who can easily hold her own against both the movie’s villains and the protagonists. It’s the second time this month we’ve seen such pull and power exerted by an older woman in a major motion picture, and it’s implemented so quickly and smoothly here that it doesn’t feel forced.

So with all these favorable marks, why am I only giving American Ultra a “maybe” for success? The movie steps wrong in two areas: one middling, and one major. The major one is Topher Grace’s CIA bureaucrat Adrian Yates. In a film that’s possessed of a surprising unification in its character approach, he sticks out like a sore thumb. We don’t buy him as a leader, or as a threat, or as any kind of force to be reckoned with. Don’t get me wrong; Grace does good enough work translating Yates to the screen. The character itself is broken; every time the movie cuts to a scene involving him, it loses traction and momentum rapidly, and the character’s escalating hysteria seems to have wandered in from another, much dorkier movie.

The middling issue is probably down to me being ungrateful toward a movie that aims higher than its target for most of its running time instead of all of it. There is a point where the movie appears to be on the verge of ending and cutting to credits; if American Ultra had done so at this point, it would have been surprising, unconventional, and absolutely fair. There is, by this point, nothing left we need to really learn about our characters, and it would have closed out this deranged little adventure on an unambiguous high point.

Instead, the movie keeps going for another four or five minutes. It’s only three scenes, really; they’re short, and they’re well-acted. Those final minutes, though, serve to let quite a lot of air out of the movie’s climactic sequence and resolution. Sometimes you don’t need to know what happens after the fireworks finish going off, and needless explication of character resolution can become tiresome. It’s honestly the most tonally moderate and commercial part of a movie that is messy, undisciplined, utterly implausible, with a reach that exceeds its grasp - but absolutely its own creature, and one that’s decidedly not assembled from the standard genre parts.