Viking Night: Midnight Cowboy

By Bruce Hall

February 5, 2013

BoxOfficeProphets.com

That's how Midnight Cowboy begins, with John Schlesinger's camera shadowing Joe's bus across the plains of Texas and onward to New York. It's an effective sequence, where Joe's back story is given to us in flashback size chunks, intercut with Voight's baby-faced mug and Harry Nilsson's dreamy, twangy theme song. It's one of several instances where Schlesinger puts us in the character's mind using the power of abstraction.

And inside Joe's mind is a heaping helping of naiveté. Because he knows his way around Bumspackle Texas, he thinks he'll be at home in New York. Instead of worrying about his future, he daydreams about his mother, who told him he looks like a cowboy, and an old girlfriend who told him how good he was in bed. There are two significant bus trips in Midnight Cowboy and for Joe, this one is like a warm, fuzzy dream.

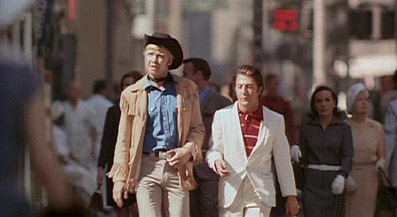

He arrives in New York with his mind full of mollifying bullshit, ready to start his life as a high priced sex stallion. He trawls the streets dressed like Audie Murphy, strutting like his pants are full of butter. The first thing he learns is that everything costs money. Second thing - being a gigolo requires at least a minimum level of business acumen. When he finally lands his first customer, he ends up paying her! Joe remains committed to his extremely stupid business model, but decides to broaden his marketing strategy.

So he hits the bars, announcing himself as a hustler to anyone who'll listen. He catches the ear of a sickly, two bit grifter named Ratso (Dustin Hoffman), who next to Joe is the second worst con man in the Five Boroughs. Over drinks (courtesy of Joe) Ratso offers to set his new friend up with representation, for a modest fee (also courtesy of Joe). The deal's a swindle, and Joe ends up broke and homeless while Ratso disappears. Yes, of course Joe will track down Ratso, but not before he's forced to do some pretty unpleasant things to survive.

You or I might strangle the man, and that’s also Joe’s first instinct. But there’s a current of decency running through Midnight Cowboy, despite some of the nastiness its characters endure. And that decency is derived largely from Joe Buck. Yes he’s as naive as a six-year-old, and he couldn’t possibly know that he looks like one of the Village People. But he’s also a hustler who hates to cheat, and a thief who apologizes for stealing. I’m not saying he doesn’t cross some rather significant lines, but mistake he makes is an increasingly desperate and honest attempt to make up for a previous one.

Bottom line - Joe’s not cut out for this, and someone needs to help him see it before it’s too late.

If you don’t believe me, look around. The whole movie is trying to tell you. The cinematography here doesn’t get enough credit. In his first assignment Adam Holender convinces even the seediest parts of New York to smile. The city is shot in a way that makes it seem more open and bright than it probably is. And for the first time I can remember, a film set in New York manages not to show us any establishing shots of the Statue of Liberty or the Empire State Building. It’s as though we’re seeing the city with the eyes of a wide-eyed tourist.

Midnight Cowboy has some bleak things to show us, it’s got a dogged optimism that never lets you truly feel bad. It’s a journey for Joe Buck, and Jon Voight - also on his first feature assignment - holds his own opposite the more established Hoffman. If you’ve never seen it before, this is one of those films that represent a rare confluence of good fortune on both sides of the camera, on the page and in the air. It seems benignly eccentric today but this is the only Rated X movie to win Best Picture, suggesting it might not have seen the light of day had it been made just a year earlier.

Be glad it worked out the way it did, because this is a slightly odd, curiously engaging film that never baffles you long enough to lose your interest. It’s a study in contrasts. It’s a little immature and reckless but it’s also earnest, attractive and strangely self assured. It’s a little like a mysterious stranger you shouldn’t feel drawn to, but do. It’s a little like Joe Buck, with his Hee-Haw shirts and social myopia. It’s worth enjoying, and worth remembering.