Sole Criterion - Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Two Takes

By Brett Ballard-Beach

October 25, 2012

BoxOfficeProphets.com

I saw Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One for the first time on December 4, 2007 at the NW Film Center in Portland (Side note: don’t marvel at me, but rather the wonderful past program archives at nwfilm.org). I was drawn to it because… well, look at that title. It’s ridiculous. It sounds like a lost Grateful Dead album from the late late late 1960s (maybe even around the time Thomas Pynchon’s private eye novel Inherent Vice is set) or some body horror Cronenberg imitator from the late ‘70s/early ‘80s. Criterion released William Greaves’ documentary/fiction/experimental mashup and its 2003 counterpart Take 2 1/2 on DVD back in 2006. The 1968 film was nearing the 40th anniversary of its completion back when I viewed it, although this year marks the 20th anniversary of its screening at the Sundance Film Festival, at which point it was probably seen by more people in a theater than it had been in the prior 20 plus years.

I had failed, however, to pursue any kind of serious look into Greaves’ career, which is handled succinctly but insightfully by a documentary on the Criterion edition, and a great essay by film critic Amy Taubin. The first Symbiopsychotaxiplasm is a revelation in that it can rightly be considered a “lost” film that continues to unfold and be discovered to this day, while the career arc of its creator (still alive) is anything but undiscovered. The briefest synopsis is in order.

Born in 1926 in New York City, Greaves first achieved a fair measure of fame working on stage (with the American Negro Theater) and in low budget message pictures (i.e. dealing with the “race problem”) in the late 1940s and early 1950s. He joined the Actors Studio, the infamous theater group out of which the likes of Paul Newman and Marlon Brando were emerging at the time, but ultimately switched his career track to documentary filmmaking. With little to no opportunity here in the U.S at the time for African-American filmmakers of any genre, he moved to Canada and worked for 10 years with The Film Board taking his time and rotating through almost every position on a film crew. When he returned to the States in the early 1960s, the civil rights movement was taking center stage, and his talents as a documentarian were soon called into service. He has been producing award winning, acclaimed and challenging works for nearly 50 years.

Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One came about - as many challenging works require - because there was an investor (a student in one of Greaves’ acting classes he was teaching) who offered to pay for the production of any film that Greaves might wish to make. Greaves had the general “idea” for the film (his production notes/thesis statements are also included in the Criterion edition) and what resulted is one of the more fascinating cinematic anomalies in American cinema. It’s an American New Wave picture with little precedent back then and because of its limited screenings in the 23 years after its release, no direct or overt influence on filmmakers of the era. It was ahead of its time back in 1968 and in curious ways foreshadows both the reality television boom and the found footage genre of the last decade.

I can imagine any number of scenarios in which this has value only as a curio, but Greaves is too skillful of a filmmaker for that to happen. He shot and shot - around 55 hours of footage it is estimated - and figured he would find the film in the editing room. This is an act of hubris and optimism and faith for any great filmmaker - from Kubrick to P.T. Anderson. He did find the film in the editing (also done by him) as well as the kind of conflict necessary to push forward any narrative, but neither in the way he might have imagined.

And what is the “plot” of the film? It’s perhaps a more enlightening question to go back to his production notes and ponder: what was the inspiration/purpose of the film? Greaves’ aim was to mix up acting philosophy, psychology, social philosophy, the politically charged dynamics of the time, race, and gender, under the guise of a “screen test” for an as yet to be determined film. Greaves had a variety of actors rehearse extended scenes (written by him in very purple prose) of two longtime lovers having a major blowout fight in Central Park. Greaves had a crew film the production crew, and then had another crew film them. His goal was to attempt to capture all the elements that impact the making of a film, up to and including outsiders who might wander into the frame, passers-by, homeless people, those who simply like to watch films being made and wend them into his cinematic stew.

The catch is that he deliberately never told any of the actors or crew that he was doing this. He wanted to see at what point they would rebel against his authority. The second catch is that because they were working for him because they respected him, they were reluctant to do just that. What resulted is one of the most fascinating cases of “mutiny on the set” ever. The crew confiscated some film and filmed themselves in roundtable/rap sessions (with more than a few blunts being passed around) to discuss among themselves exactly what in the hell was going on. Greaves never saw this footage until production was complete. In pushing back against him on the sly, they unknowingly added to the project’s success, by giving Greaves a Greek chorus who usually manage to mirror any given audience’s general reaction by the time they show up on screen (after the first reel). With that said, it may be easiest to catalog a few reasons for what makes Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One so compelling and, yes, entertaining.

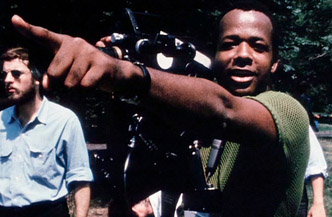

Reason #1: Greaves is charismatic and handsome and ingratiating, and an impossibly young looking 42-years-old. I don’t wish to reduce him to looks, but since he is onscreen as much as his actors and crew, it helps that he has a pleasant visage and a charming demeanor and adopts the complete opposite of a dictatorial personality. He does sway between sporting a slightly naïve tone at times and other times where he leaves no doubt that he knows what he is pushing his cast and crew towards, but he also remains impossible to read through his actions.

Reason #2: His decision to cut in the “rap session” footage filmed in secret by his crew. As he acknowledges in a 2006 interview, their rebellion gave him something to use as dramatic conflict and it was in line with one of his stated aims for the project to achieve, but it was also a bold act for him to offset the image he projects during the film production with the less rosy view his collaborators take of him in their discussion. It resembles nothing so much as the confessional camera in any number of reality shows (Big Brother, Survivor, The Bachelor), but with intelligent discussion instead of just strategy, motives, and disses.

Reason #3: Bob Rosen. With his nerd’s glasses, white t-shirt hipster facial hair, and “what, me worry?” facial expressions, production manager Rosen leads the charge in the crew’s grievances, but comes across as the philosophy undergrad you wouldn’t mind passing the bong around with on the weekend. He tends to dominate the discussion but also helps guide it along. He is comic relief, audience surrogate, and an articulate instigator all in one. And if his IMDb filmography is to be believed, he went on to produce everything from Gilligan’s Island to Strawberry Shortcake specials to The Crow to late ‘90s Leslie Nielsen comedy spoofs. I have nothing to add regarding any of those.

Reason #4: Don Fellows/Patricia Ree Gilbert. We see glimpses of the other acting pairs (especially the two at the end who become the focus of Take 2 1/2) but Fellows and Gilbert log the most screen time here and rescue Greaves’ intentionally hyperbolic and unsubtle dialogue by digging into it like the trained stage actors they were, elevating their characters’ subpar Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf roundelay into something approximating poetry. Their inherent likeness also offsets the shrillness their arguing can descend into. It helps that they look like the archetypal mismatched couple of the late 1960s: square dude squarely on the side of the Man and fallen, middle-class hippie chick. Fellows went on to a distinguished career of bit parts, including turns in Raiders of the Lost Ark, Superman II, and Velvet Goldmine.

Reason #5: The running time is only 75 minutes. Greaves’ editing may be the most notable aspect of this project, as he finds a through line with a recognizable beginning, middle, and ending, kicked off by an appearance by a homeless Central Park denizen named Victor, who finds his own kind of gutter poetry. I don’t normally praise movies for their length (long or short) but this project could have easily felt interminable - and may anyway for some - and Greaves takes his experiment just about as far as it will go.

Reason #6: Good vibes (but…). From the original jazz score by Miles Davis to the sunny NYC spring to the (mostly) upbeat attitudes of Greaves and his crew, there’s something inherently reassuring in the very foundation of the film’s being. A multi-cultural crew wills an awkward and gangly experiment into being in the weeks (if I am right on the timeline) just before Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. And yet, like a fly in the ointment, the feedback that Greaves captures and slips onto the soundtrack, underneath Davis during the opening and closing credits, speaks to the dissent and protest that were a part of the time, and the lesson he hoped to impart on resisting authority figures.

Thirty-five years later, Greaves pulled a chapter two (thanks in part to the collaboration of Steve Buscemi and yet another interested party’s funding, this time Steven Soderbergh) and revisited his experiment. I only watched it once and so these are simply some cursory thoughts. I liked it less in many ways than the first one (particularly in regards to the six reasons I listed above) but I also found it to be more emotionally honest and genuinely upsetting in key moments towards the end, as it plays viciously with art vs. life and acting vs. reality. Take 2 1/2 could have easily fit in Chapter Two as it also functions on the various tactics a director can employ in making a sequel. A few examples:

#1: Give the audience more of the same. The first one-third of the 99-minute running time is made up of another “screen test” from 1968, with a different couple (a Caucasian male and an African-American woman) running the dialogue. After a brief interlude that captures the reaction of a crowd at a late ‘90s/early ‘00s screening of Take One and thoughts from the crew who are about to accompany Greaves on his latest venture…

#2: Give the audience something new. The final 45 minutes plays mercilessly with whether the actors are in character or not, revisiting their 1968 roles, and grappling with an entirely new scenario, or playing something a little closer to their real lives.

#3: Incorporate the passage of time. Shannon Baker and Audrey Henningham have aged, lived-in faces that contain great sorrow and weariness, yet also conceal smiles and warmth. The contrast of their young selves in the first half and their “now” in the second half is effective from a visceral point, but Greaves gives them a much stronger and realistically written scenario to act out, even as it reaches for maudlin notes. The actors’/characters’ anger undercuts any cheap sentiment.

#4 Interact with your original. What I take away is Greaves’ serious attempt to comment on and expound upon his original experiment with the point of view that only three decades of distance can help provide. Like his new scenario, it’s a way of opening old wounds in order to help them better heal. If it seems a lot crueler than Take One, I would agree it is. Even he is taken aback by where the final dialogue between Freddie (Baker) and Alice (Henningham) leads but all three come through the other side together.

Next time: Precursor to Pan’s Labyrinth? DVD Spine #351