Chapter Two: Beverly Hills Cop II

By Brett Ballard-Beach

August 30, 2012

BoxOfficeProphets.com

I quickly realized that I had a conception of “Tony Scott”, but little to no inkling of the real person via interviews or recollections of others, to the extent that I couldn’t vouch for certain if I had even seen a publicity still of him on the set or a red carpet shot at the premieres of one of his features. For the last 30 years, it just seemed inevitable that there would always be another Tony Scott film, one that more often than not would be commercially successful (critically perhaps less so), that would get lauded for style over story, ambience and sleekness over emotional accessibility and narrative coherence.

And as is so often the case, that “general consensus” consists of surface appearances alone (which might be an appropriate allegory for someone who worked with producers Don Simpson and/or Jerry Bruckheimer on over 1/3 of his oeuvre). Aside from his first film being a horror film, all of his other features might best be described, retrospectively, as Tony Scott action films. His biggest financial successes came very near the beginning of his career (back to back with 1986’s Top Gun and 1987’s Beverly Hills Cop II) but his smaller successes and even his commercial “busts” (his debut with 1983’s The Hunger, 1990’s Revenge, 1993’s True Romance, 2005’s Domino) are perhaps a better evocation of his strengths and trademarks: the ability to craft live-action cartoons that paradoxically possessed emotional resonance; fragmented hyperkinetic editing that could become viscerally wearying or punishing but that seemed necessary to capture his protagonists’ frequently upended lives , jittery nerves and tortured below the skin psyches (re: his four collaborations with Denzel Washington in the ‘00s), and ensemble casts that centered around a big name or two but that often allowed bit parts to make an impression, often in only a few minutes, even in the midst of all the sound and fury.

The portrait that emerged in the pieces of praise and memoriam over the last week painted a picture of a larger than life figure, very nearly a caricature (who might be at home in one of his own features), but one who was generous with his success and with his on-set collaboration. Clad in an always present pink t-shirt and pink baseball cap, with a history of speed-car racing, bare hand rock climbing, and chomping stogies for breakfast, he looked like Lawrence Tierney’s more chipper brother and seemed as if he would have been at home grappling with Ernest Hemingway (if not the man, if not the myth, then at least the serenely machismo portrait on display in Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris.

I noted, to my surprise, that I had seen all 16 of his theatrical full-length features (beginning with 1983’s The Hunger on through to 2010’s Unstoppable), half of them in the theater, but many of them only once, a fact I am rectifying by revisiting those in weeks to come. To date, I have viewed The Hunger and The Last Boy Scout. I believe that film, True Romance, and Crimson Tide together represent a streak of bravura commercial American filmmaking from the last 30 years. As the latter two are often heralded as his greatest achievements, the inclusion of the former may cause some perplexity. For comparison’s sake, I want to briefly delve into it before turning to Beverly Hills Cop II.

It had been about 20 years since I had seen The Last Boy Scout, but it played out like it had been only yesterday, while the level of outrageous, escalating violence still managed to sucker punch my gut. Out of the three directors who filmed screenwriter Shane Black’s archetypal satirical gonzo buddy comedy action demolition spectaculars of the ‘80s and ‘90s (Richard Donner for Lethal Weapon and Renny Harlin for The Long Kiss Goodnight were the others), Scott may have been the most apt pairing.

Underneath the explosions, mayhem and car chases is a fairly faithful updating of the existential private eye figure from 1970s American cinema (chiefly Philip Marlowe in The Long Goodbye and Harry Moseby from Night Moves) mashed up with the popular one black/one white buddy cop movie genre that was then in vogue. Scott’s affinity for the bruised loner suffuses the project with an unexpected gravitas that allows the movie’s most emotionally potent moment - a monologue by Damon Wayans’ character on the loss of his wife and child and his fucked-up life in the aftermath. Coming at just about the midway mark in the film, it is a sequence whose stillness is marked even more by the almost wall-to-wall action on either side.

Bruce Willis was never more disheveled (while still sporting a full head of hair) than as disgraced Secret Service agent turned low rent private dick Joe Hallenbeck, whose signature moments are fishing someone else’s still smoldering cigarette out of the gutter to save on buying a new pack, and punching a hood so hard in the nose it drops him dead on the spot. As he wends his way through a convoluted plot involving blackmail, political corruption, and an attempt to legalize sports gambling, he picks up an unwanted sidekick, a disgraced quarterback (Wayans) whose girlfriend has been murdered, attempts to resolve issues of marital infidelity with his wife and connect with his mouthy and emotionally distant daughter, and tangles with a seemingly endless menagerie of chatty, homicidally inclined henchman - wonderfully embodied by the likes of Badja Djola, Kim Coates and Taylor Negron, the latter channeling Martin Landau’s character from North by Northwest - who wind up stabbed, shot, set on fire, exploded and stabbed/shot/eviscerated by helicopter blades.

There is no top that isn’t eventually gone over. My favorite shot is a perfectly framed moment of an upside down car crash landing into an aghast mansion dweller’s pool. It’s the excess of the entire film distilled into three seconds. Elsewhere, the opening credits sequence - a slick production video for “Friday Night’s a Great Time for Football” sung by Bill Medley (from The Righteous Brothers) is filled with enough patriotic jingo to qualify as a lost image from the Parallax Corporation’s assassin screening test. It’s so effectively blunt in aping the real thing that its comic and satirical nuances may not be fully appreciated.

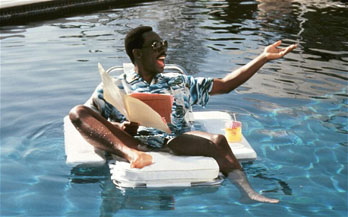

Beverly Hills Cop II, by contrast, features Scott, who jokingly referred to himself once upon a time as a “director for hire” for Simpson/Bruckheimer, filling that role succinctly for them, or anyone, for the only time in his career. It is the only sequel in his oeuvre (Days of Thunder remaking the Top Gun template notwithstanding) but it is also the only one in which a single star performer holds court over the proceedings and the ensemble cast in support is given precious little to do or to with which to work. The script, based on a story for which star Eddie Murphy is given co-credit, is so lax in regards to every plot development in which Axel Foley is not involved, so uninterested in every character other than Foley (aside from allowing it to register that Taggart is on the outs with his wife and Rosewood has a serious gun fetish) that not even the villains, a disparate trio played by Jurgen Prochnow, Brigitte Nielsen, and Dean Stockwell are allowed to register as presences (let alone malevolent presences) that we have any opinions on, let alone want to see get their comeuppances.

The plot developments with regards to what the villains are doing and what they hope to achieve are fairly incomprehensible (bank robberies to serve as setup/diversion for a case of insurance fraud in order to raise money to then flee the country with cheaply bought munitions which will be sold on the black market in South America. . . I think), which leaves the majority of scenes to Murphy to do his shtick, play off against the uptight, the unwitting and the foolish. In most cases - a stuffy maître’d at a high-end strip club, receptionists at the Playboy Mansion and a shooting club - the interplay falls flat. The two exceptions are Gilbert Gottfried’s three-minute bit as a blithely corrupt accountant and Gil Hill, a real-life policeman, reprising his role as Foley’s infinitely exasperated superior, Inspector Todd, perhaps the finest performance in the realm of commanding officers chewing out their subordinates. In their own ways, Gottfried and Hill find a way to play along with and push back against Foley/Murphy and create dynamic and comic tension.

Lacking the first film’s fish out of water conceit and Martin Brest’s deftness at mixing broad comedy with unexpectedly jarring violence, Beverly Hills Cop II plays like what it is: a defining example of an unnecessary sequel, created by the “demand” of a predecessor that spent 14 weeks at #1 and seven months in the top 10, unexpectedly grossing over $230 million and receiving critical raves. Skipping even the expected cliché that this might start out in Beverly Hills and wind up back in Detroit, it settles time and again for the easy laugh, or barring that, winds up for the laugh and then stops at the setup (Paul Reiser’s character and some business involving the car he borrows from Foley and the outcome of Foley’s undercover sting against some credit card fraudsters are both built up and then futz out.

With no stake in his leading character, one who most definitely goes against the grain of all others in Scott’s subsequent films, there is a loss of an emotional touchstone, a way to infuse the comic and violent shenanigans with anything deeper. To tether this to a musical analogy with some relation to the film, his work here is the equivalent of Bob Seger and the Silver Bullet Band recording a glossy corporate rock number/theme song like “Shakedown” (which, by the by, became their only #1 Billboard Top 100 hit), which can be enjoyed but doesn’t satisfy like “Night Moves,” “Mainstreet” or “Turn the Page.”

The pre-credits and opening credits sequence illustrate this in miniature: a heist sequence in Beverly Hills filled with quick cuts and an overabundance of smashed glass and guns fired to the ceiling, followed by Foley back home “suiting up” in designer duds up for his undercover gig, a glaring example of how he (and the film) has subsumed the materialist mentality. Actually going back to Beverly Hills proves to be redundant. (As is a third title card which after the opening scenes in Beverly Hills and Detroit assures us that yes, we are back again in Beverly Hills, as if Captain Bogamil’s presence might be more confusing than helpful. I briefly mused that these would continue for the duration of the film).

Even the pile driving action sequences - a ridiculous chase sequence involving an armored truck and a cement mixer, the final shootout at ranch facilities adjacent to oil fields - don’t seem sufficiently larger than life, imbued with iconic forcefulness like shots of jets on runways in Top Gun or Peter Murphy in a cage deadpanning “Bela Lugosi’s Dead” into the camera. It is, if I may misuse the word, all a little too tasteful in Beverly Hills Cop II. And safe. While it may be overstating the point to say that Scott veered away from the likes of Beverly Hills Cop II, I think that once he had the freedom to choose only the scripts he wanted and settle on the projects that spoke to him, he was able to share that connection in the finished film. I am sad that he is gone.