Viking Night: Taxi Driver

By Bruce Hall

May 17, 2011

BoxOfficeProphets.com

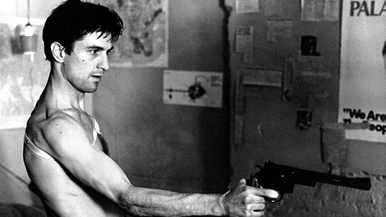

Like the Protagonist in Fight Club, Travis Bickle (Robert DeNiro) has mentally unraveled into fits of sleeplessness and depression, and this is what sets the story in motion. Since he can’t find slumber he drives his cab almost constantly, which means a fat payday for this enterprising delusional insomniac. But the on the job conditions are borderline medieval, and the hours take their toll quickly. When he’s not hauling johns through filthy neighborhoods to pick up hookers or cleaning bloodstains off the back seat of his cab, Bickle can be found hanging around porno theaters trying to look invisible. His diet consists of potatoes and milk, washed down with Alka-Seltzer. Sometimes he scribbles random, violent thoughts into a tattered journal or lies in bed staring at stains on the ceiling. It’s not a very healthy life, but Travis Bickle is not a healthy man. And he exists in a state of mental isolation so profound that when the inevitable need for structure in life finally hits him, it overwhelms him.

So, he responds the way any self respecting paranoid schizophrenic would - by developing fixations. First there was that punishing job schedule, designed to keep Bickle’s agitated mind occupied. For a while it works, and then he begins to obsess over an idealistic campaign worker named Betsy (Cybill Shepherd) who’s in the middle of trying to get her boss elected president. At first Betsy is intrigued by Travis’ odd habits and quirky verbal tics, but their relationship quickly becomes yet another trigger for Bickle’s slowly evolving state of lost marbles. Later, Travis takes up the case of an underage streetwalker named Iris (Jodie Foster), who works the intersections under the watchful eye of a sadistic pimp named Sport (Harvey Keitel). Iris doesn’t like what she does but has little choice in the matter, as Sport keeps her plied with drugs and the threat of violence.

At the beginning of the film, Bickle blames society for his feelings of isolation and had already started thinking of ways to lash out against the world. But in Iris, for the first time he is able to see someone else as a victim and he begins to consider directing his resources toward something worthwhile. There’s no question Bickle is a ticking time bomb, and that he’s eventually going to go off. The mystery is which way he’ll direct the blast.

Will he do something foolish and go out in a blaze of glory, taking innocent lives with him? Or will he take his contempt for civilization and use it to help a brutalized little girl who just wants to go home? The answer can be taken any number of ways and because of this, it reminds me a little of the famous ending of A Clockwork Orange. You catch yourself feeling reluctant pangs of sympathy for what 20 minutes earlier was a completely loathsome character. Can villains be victims, too? And if they can be, who’s responsible for that? That’s really the creamy center of this movie, the theme that we live in a disastrously hypocritical society.

It’s a complaint Bickle rambles on about for the whole movie, but what he fails to realize is that he too is part of the problem. We all are. We tend to enjoy finding fault with those who are more gifted and fortunate than we are. We enjoy lifting up those who don’t deserve it because it makes us feel charitable or superior. We struggle with empathy, project our anxieties onto others and we lord it over others when we think we’re right. And most of us have great difficulty admitting that we are the cause of most of our own problems.

Taxi Driver is one of those movies where the central character is really YOU, and everyone on screen is executing a scenario for you to consider. Your job is to decide whether or not you want to keep making the same mistakes with your life as they do with theirs, even though you already know you will. Or at least, that’s what this movie wants you to believe. I don’t know if I’m all that cynical, but you don’t have to agree with who’s asking for a question to be worth discussing.

If you’re going to write a retrospective on Taxi Driver, I guess you kind of have to mention John Hinckley. I was going to avoid it, because that conversation really is as stale as a day old bagel. It’s also beyond the scope of this article. But it does bear mention because for some, there’s a stigma attached to this film and I don’t think that’s fair. It has been argued that the man who shot President Reagan was obsessed with this movie and derived at least some level of inspiration from the story. Of course, Hinckley missed the point of the film, but so do many of the critics who tie the two together. Some of the same people who claim that Hollywood is out of ideas would also have you believe that Paul Schrader and Martin Scorsese invented the eccentric loner. In reality, the character of Travis Bickle was heavily based on the man who shot George Wallace in 1972. This means the movie that supposedly inspired the nut who shot the President was itself inspired by a different nut who shot a different politician. It seems to me that crazy is as crazy does. Art doesn’t imitate life so much as art becomes a prism through which we view life.

On its own merits, Taxi Driver is a haunting (and disturbingly realistic) look into the mind of an unbalanced man who lets his sickness twist his view of the world. But the world suffers from its own set of delusions, and because of this we don’t always identify these people until it’s too late. When you consider how close killers like Booth, Oswald and McVeigh came to being caught before they acted, it’s even more chilling to see one person after another fail to see how badly Travis Bickle needed a friend, a hand, a doctor.

I’m not suggesting we all run down to the nearest porno house or taxi service and sign up for the Adopt a Psycho program. But understanding others is just as important a part of life as understanding yourself, and on most days I don’t see a lot of people working on that. I’ve felt this, but in a slightly new way each time I’ve watched Taxi Driver. To me, the way it makes me think about myself is part of what makes this such an enduring film. More than many other films, Taxi Driver truly qualifies as a work of art. but maybe it’s even more than that. Maybe it’s a prism (see how I came back to that?). And maybe it’s one that everyone - not just the Travis Bickles of the world - should take the time to look through.