Chapter Two: The Color of Money

By Brett Beach

May 12, 2011

BoxOfficeProphets.com

As I wind up two full years of the most notable part twos and look ahead to a third, I have decided to mark that passage of time by focusing on the passing of time...in movies. For the next several months, Chapter Two will hone in on second installments that took anywhere from 13 years to nearly 30 years to finally hit the big screen. Several of the sequels are adaptations of books that themselves took a long time to come to fruition. (Hence, a reasonable explanation for the lapse of time.) What can you expect?

Larry McMurtry source material and multiple appearances by Jeff Bridges, for starters. There are Academy-Award winning performances that have defined an actor or actress, and roles that became so closely entwined with a particular actor that it was both blessing and curse simultaneously. We begin with a Chapter Two 25 years in the making that brought its lead actor his first and only Oscar after receiving seven nominations (he would go on to receive another two, and several honorary Oscars before his career was over).

If pool shark Fast Eddie Felson isn’t the defining role for Paul Newman - I would actually accord that honor to his seriocomedic portrait of washed up hockey player/coach Reggie Dunlop in Slap Shot - it provides an apt encapsulation of the blend of heartbreaking gorgeousness, cocky attitude, stubborn demeanor, and wounded pride that marked his career. Coming on the heels of his first nomination (for Cat on a Hot Tin Roof in 1959), his role in The Hustler kicked off a decade that would see him play titular characters as memorable as Hud, Cool Hand Luke, Lew Harper, and Butch Cassidy, and get additional nominations for the first two of those performances.

Fifty years after its release, The Hustler still strikes me as one of the more unconventional Best Picture nominees of all time. Yes, it’s in black and white and is an adaptation of an acclaimed novel, but it feels so otherworldly in certain moments that it doesn’t quite fit the requirements of “Oscar bait” and moves at such a deliberate pace and with such a hushed and muted tone for much of its 135 minute length that it certainly doesn’t qualify as a crowd pleaser, and yet it succeeded on both counts in 1961. The key dramatic moment - a marathon pool session between Felson and legendary player Minnesota Fats - has passed with barely the half hour mark cracked and what follows, even with more than a few twists of the plot thrown in, feels like epilogue in a way.

Even in black and white, Newman’s startling baby blue eyes electrify in what is at heart a tale of someone who, to paraphrase another Best Picture nominee, is a character but doesn’t yet have character. The Hustler is the story of how he gains that attribute, at the ultimate expense of his livelihood. Filmed mostly indoors for the first half, the better to exploit the claustrophobic feeling of being inside a pool hall for hours on end, with daylight (and real life) kept at bay behind shuttered blinds, The Hustler at times feels like the adaptation of a stage play. While I don’t count myself as a fan of Tennessee Williams’ work, a familiarity with his style and the knowledge that Newman had starred in multiple adaptations of his works makes it easier for me to see The Hustler as a variation of sorts on the Southern Gothic genre. Call it Northern gothic. Nothing particularly grotesque happens, but there is a sense of all sorts of depravities and excesses lurking of in the wing. By the time the weak climax rolls around, what has been mostly underplayed and covert, to great effect, is spelled out in dialogue that sounds a little too forced and explanatory and stagy.

Newman may have the title role, but an also-nominated ensemble surrounds him and they all contribute to the film’s atmosphere of desperation. George C. Scott, in one of his earliest feature films, is all oily charm (in the first half) and banal evil (in the second half) as Felson’s bankroller, a gambler with all the luck until his veneer finally cracks at the end. Piper Laurie (in her last feature film for nearly 15 years) begins by toying with Felson, only to fall into a relationship and then love, and is tragically forced to confront the limitations of what she and Felson can truly feel for one another. And as Fats, Jackie Gleason provides definitive proof of why comedic actors can sometimes be the best choice for deeply dramatic roles. Wearing the air of a disinterested god, a being so good at the sport of pool, he is doomed to an endless ritual of fending off challenges from the young Turks who would snatch his crown, Gleason’s visage is as immutable as stone, and yet no less tragic for being so unreadable.

Why did it take so long for The Hustler to inspire a sequel? Simply put, because it took The Hustler author Walter Tevis 25 years to write the book sequel, which was published in 1984. (It should be noted, strangely enough, that the movie adaptation shares the book’s name but bears virtually no resemblance to that story, which picks up on Felson in middle age, and sets him off against Minnesota Fats on an oldies circuit.) As with the quick turnaround with The Hustler’s transformation from printed page to celluloid, The Color of Money only took two years to grace the big screen, debuting in October 1986.

It was a modest-sized hit, grossing about $53 million and spending five weeks at #2 (all of them behind the year’s second-biggest hit, Crocodile Dundee). Part of that popularity can be accorded to the presence of Tom Cruise in the film. Top Gun was still in the midst of its year-long assault on the box office - and the beginning of a lifelong assault on sensibilities such as mine - which would ultimately help it beat out its Paramount mate by less than $3 million to become the year’s highest grosser.

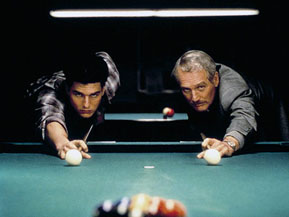

The Color of Money is also the start of Cruise’s mini-film career of playing the mentee to an older and (supposedly) wiser male figure who helps him to see the error of his cocky ways and/or gain a measure of maturity (see Cocktail, Rain Man, Days of Thunder, The Firm). Visually, this is aided and abetted by the fact that although it was filmed immediately after Top Gun wrapped, The Color of Money somehow showcases a Cruise who seems both impossibly young, and younger-looking than Pete Mitchell (I think it’s because he’s out of the military duds and flashing those pearly whites every 30 seconds).

From the opening scene until the very finish, The Color of Money forces the audience to consider Vincent Lauria in the context of Fast Eddie. We can see Vincent in the background behind Fast Eddie at the bar even before the latter really becomes aware of him, and reminded of him at that age. The advertising and poster art for the film drive home the point that Vincent is an heir apparent to “the hustler” but the film really doesn’t. Aside from a few vague references, there are no plot shout-outs to The Hustler. Fast Eddie could be any aging once-upon-a-time big shot with an eye for talent and a rediscovered lust for the action. It’s both a wise move on the film’s part (I would be curious to know what portion of the initial audience was aware of and/or had seen The Hustler) and a bold move that doesn’t quite pay off.

Despite a screenplay by crime writer Richard Price, The Color of Money doesn’t have much of an air of that genre, or any genre for that matter. While the original played out with an air of tragedy and the slightest tastes of the unsavory, its follow-up is an unapologetically commercial entertainment that electrifies in individual moments but is relatively shapeless in form and plot. It flirts with being a buddy comedy-drama, a road movie, and a tale of redemption, but it never quite commits strongly enough to any of those. There is an unexpected twist right near the very end that sets up what promises to be a climactic showdown, before the story sidles off into an ending that is as deliciously unresolved and open-ended (although completely polar in tone) as that of The Hustler.

In Martin Scorsese’s long and winding oeuvre, The Color of Money is an oddity in several ways. It was his biggest commercial hit by far of the 1970s and 1980s. It came in the midst of his stretch to find other projects, post-Raging Bull, to keep him occupied while attempting to get The Last Temptation of Christ off the ground. This creative meandering resulted in a black comic take on Taxi Driver (The King of Comedy), a Kafkaesque nightmare comedy (After Hours, my favorite Scorsese film), an episode of Amazing Stories and the video for Michael Jackson’s “Bad”.

The Color of Money has the design and shell of a Scorsese, but thematically feels very lightweight. It is first and foremost a sports picture, and in its rendering of the electric charge in the air that can accompany a tight game of nine-ball, it succeeds at finding a way for the crisp and vibrant color cinematography to compete with the haunted blacks, whites, and grays of The Hustler. Odd or not, it most reminds me of Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, Scorsese's 1974 follow-up to Mean Streets that shares the entertainment value of The Color of Money, and is a film more concerned with relatively low-stakes character arcs than plot antics.

While Vincent seems to be an open book, both Fast Eddie and Vincent’s girlfriend, Carmen, remain at times maddeningly opaque in regards to their motives. This is the bold move I referenced earlier. The plot may be relatively straightforward, but courtesy of Price’s dialogue, they are able to speak around their feelings. Both of them may only be using Vincent to take them as far as he can, but they also care for him on some level as a son figure and a lover, respectively. Newman provides strong combustion with actress Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio (who, it is worth reminding, also snagged a nomination for her work) and it is a pleasant upending of clichés that they don’t wind up sleeping together.

This disconnect between the Fast Eddie that we might remember or expect and the one on-screen is what keeps the film emotionally at bay for me. Newman’s performance is solid but he doesn’t seem like Fast Eddie 25 years on. He is charming and spry, and leveled with just the right touch of gravitas, but he never seems haunted enough. It becomes apparent early on that the character of Fast Eddie is simply being shoehorned into a tale where he doesn’t really belong and where he has to play second banana. This doesn’t render The Color of Money a loss, but, as typified by the generic Robbie Robertson and Don Henley-driven 1980s score and soundtrack, it makes it more a product of its time than something with the power to become timeless.