Chapter Two:

The Testament of Dr. Mabuse

By Brett Beach

January 6, 2011

BoxOfficeProphets.com

If Roger “Verbal” Kint had ever encountered German super villain Dr. Mabuse, he might have felt compelled to alter his statement. Featured in five novels and over twice as many features since his first appearance in the 1920s, Mabuse stands as a direct forebear to any number of evildoers over the last near-century: from the world of comic books (Lex Luthor) to Ian Fleming’s spy novels (Dr. No and Blofeld) to parodies of the same (Dr. Evil) and even to singular personifications of evil (Dr. Lecter), Mabuse is the archetype by which all those who desire world domination and/or destruction should be measured.

Director Fritz Lang in three separate features released in 1922, 1933, and 1960 brought Mabuse’s most infamous exploits to life. During a 15- year stretch from the late ‘10s to the early ‘30s that included the first two Mabuse epics, Lang also directed such classics as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Metropolis and M, while living in Germany. After the second Mabuse film was banned at the time of its completion by the German government, Lang fled to America and a new career in Hollywood. He did not return until 25 years later for what would prove to be his final film as director.

I watched the first and second features in Lang’s trilogy - Dr. Mabuse the Gambler and The Testament of Dr. Mabuse - for the first time this past week. I have not yet seen The 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse, though I soon hope to remedy that. Even so, with a little knowledge of the plot of the latter film, it is fascinating to me to chart progression in the three films, from silent black and white (accompanied by an original score on the 2001 Kino Video edition DVD) to sound black and white to Technicolor; the transformation of Mabuse from a seemingly omnipotent (though still flesh and blood) leader of the criminal underground to a ghost in the machine able to manipulate actions from beyond the grave and remain unchallenged in a quest to establish an “empire of crime” that will collapse the world in anarchy and violence; and running times that vary considerably (esp. in the multiple versions of the first two films) but that as a rule wind down from the epic serial nature of the first (around four-and-a-half-hours) to the slightly more manageable 99 minutes of the third.

As aware as I have been of Lang’s Mabuse films, they have conspicuously remained filed away in my internal Movie Viewing Directory under the heading of Classic Cult Films I Somehow Always Seem to Put Off Until Tomorrow. (I would also slide under this quite bulging and unwieldy header two movies about Hollywood in the ‘30s, The Last Tycoon and The Day of the Locust, that I was always waiting to view until I had read the F. Scott Fitzgerald and Nathanael West novellas on which they were respectively based. With that accomplished over the past month, my excuses for avoiding them have run out.)

I am embarrassed to admit the extent of this avoidance of Lang’s films was so complete that I did not even know the proper pronunciation of his master criminal’s last name. I had presumed it was Mah-byoos, to rhyme with abuse and, if one considered it as an inside joke in broken French: m’abuse, or I abuse myself. Since the first film has intertitles only, and no spoken aloud dialogue, it wasn’t until halfway through The Testament of Dr. Mabuse that I could hear it properly delivered as Mah-boo-say. This is humorous and it must be said, more than a little ironic.

Mabuse’s name, its invocation, and the secret (or lack thereof) of his identity are actually turning points in both of the first two films, with the former almost a subtle running gag. People are forever on the verge of uttering his name aloud to make the identification that he is the villain in question, only to be silenced, either by forces wrought by Mabuse’s control (a city full of organized henchman as adept with vintage pistols as they are with exploding drum cans) or beyond the control of the individuals themselves (mind-control and manipulation or paranoia that easily slides into full-tilt madness).

Mabuse hides in plain sight in the first film, as a respected lecturer and psychiatrist who involves himself in the lives of those he corrupts and ruins, while also disappearing behind an endless array of quite genius disguises as he determinedly works his destruction in the stock markets, gambling dens, and music halls of his city. Mabuse lurks in the darkness in the second film, mute from madness, he is presumed to be incapable of menace from behind the walls of the mental institute that has been his home for over ten years. And yet, he exerts his psychic power over those who think they control him and ultimately appears to carry out his grand design from beyond the grave. Depending on how you take the meaning of the word Testament, you could conclude that this was a triumph of the “will” equal to the real-life one documented by Leni Riefenstahl 2 years later.

The Testament of Dr. Mabuse is not only a sequel to the events in Dr. Mabuse the Gambler, but contains a running commentary on the phenomenon of the Mabuse figure himself. Lang, working as he did on the first-go-round from a script by his wife Thea von Harbou, does so in a winking manner early on, as a room full of graduate students, who perhaps only know the name of Mabuse as a whispered-about bogeyman from their not-so-distant childhoods, collectively recoil in horror when shown a slide of Mabuse by their professor Dr. Baum, who also oversees Mabuse’s daily routine.

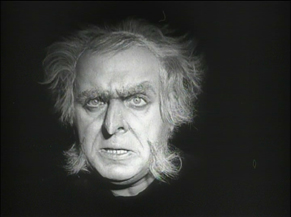

With his electro-shock white hair and accusing gargoyle features, Mabuse (played once again by the indispensable Rudolf Klein-Rogge) casts an imposing shadow over the film, even though his on-screen time is well under 10 minutes of the two-hour length and his voice is featured for even a shorter amount of time. In a brilliant narrative decision that only becomes apparent in retrospect (or if you have been fortunate enough to read well-argued analysis in advance of seeing the film), Mabuse is never seen AND heard at the same time.

In the psychiatric ward, Mabuse is silent and catatonic after a fashion, his only effort directed toward a near-constant stream of scribbling. In the room where Mabuse’s underlings receive their orders to kill and cause mayhem, instructions are issued – Wizard of Oz-like - by a shadowy figure seated behind a curtain. In a dramatic unveiling in the film’s second half, it is revealed that the “person” is a cardboard cutout and the voice emanates as a recording from a phonograph. The one moment that comes closest to achieving a body and voice unity - when Mabuse’s spirit appears to enter and control Dr. Baum - features Mabuse’s features distorted by a grotesque death mask.

While Dr. Mabuse the Gambler is a rambling and not entirely successful epic, it places a premium on a dense, sprawling narrative that nonetheless remains comprehensible and on characters that work within, instead of being controlled by the plot. Structured with 12 acts that unfold over two distinct parts (full movies actually, running 155 minutes and 115 minutes in the “definitive” version I viewed), its mammoth running time gives it the feel of a serial with any number of cliffhangers. It also concludes with a wrap-up built around very definitive moralistic underpinnings.

The Testament of Dr. Mabuse is more of a nightmare that unfolds with the logic that can only punctuate dreams or their dark mirrors. Holding this logic up to the light of the day is an act in futility. An attempt to accurately synopsize the plot, as you may have gathered from some of my thoughts above, can only lead to frustration and ridicule. Questions such as - How did Mabuse’s voice get recorded? Do any of the underlings know that their boss isn’t really “all there?” What happens to Hofmeister to drive him insane? - aren’t so much raised as slightly elevated and left dangling. Lang plows through them all to create innumerable sequences of “pure cinema - moments that exist on their own and carry the picture securely over any plot-based objections.

The opening five minutes contain no dialogue and no musical score of any kind, only the ambient, increasingly unnerving sounds of industrial pipes and machine noise as an undercover policeman attempts to elude capture and avoid detection inside a factory. The sounds are so grating (and unexpected) that my first thought was my speakers were on the fritz (unintentional pun, sorry.)

Lang could have easily begun the picture with the act of narrative that immediately follows: Hofmeister calling his former boss, Inspector Lohman, and frantically attempting to convince him that he now knows the name of the man behind the nefarious illegal activities in their city. As mentioned previously, the fact that Hofmeister is deigning to announce the Name that Dare not be Spoken doesn’t bode well for his future safety or sanity.

By opting for so disorienting and unsettling a prelude, Lang immediately establishes the tone of unease and uncertainty that pervades the rest of the film. Thus, even when the narrative becomes more conventional at times, working in crime drama stand-bys like the felon angling for redemption, a possibly ill-fated love affair, narrow escapes from death and betrayal, and a breathless auto chase in the dead of night, Lang finds a way to use sound and/or image to keep the audience off balance.

Example 1: When Mabuse’s schemes are close to being revealed by an interloper, the offending party is assassinated at a stop light, behind the wheel of his car, the noise from the gunshot drowned out by a chorus of angry auto horns that swell and then fade away, as if by design. Lang builds the sequence out of well-chosen quick shots, and gains emotion with an overhead angle of other cars pushing forward or going around the now-lifeless vehicle.

Example 2: In a thrilling mini-drama midway through, two people attempt to escape from a room with no windows, no door to open from their side, and a bomb in the floorboards beneath them ticking out a chilling commentary on their hopelessness. The resolution to the suspense may seem improbable, but Lang draws out the plight by cutting to an unrelated monsoon of a shootout between police and gangsters across town, gangsters who feel trapped themselves. Lang traverses these two encounters skillfully, keeping the momentum kinetic on both ends by cutting back and forth at just the right moments. He establishes the boundaries and dimensions of the two entrapping locations and explicitly lets the audience feel the desperation of the individuals inside. One of the scenarios ends positively, the other not so much.

Example 3: In the extended car chase that helps draw the picture to a close, Lang even finds time for our heroes to change a flat and still stay within spitting distance of their target. That may be hopelessly naïve, yet it’s also charming. But I digress. Lang opts to use rear-projection (placing his actors in front of a screen and cranking up the wind machine to simulate them speeding) for less than half of the chase. The rest of the time, footage is presented as if shot from within the speeding cars themselves, looking up, down and ahead to the consuming blackness. Trees whirl by, curves loom unexpectedly; faint headlights appear ready to be sucked into the night. There is a surreal and Lynchian aspect to these moments, as if all bets are off, and no answers lie at the end of wherever the road leads.

And where does that road lead? To a resolution of sorts, but one that conceals as much as it reveals, that creates new life for Dr. Mabuse even as it appears to trap him once again, that can leave a lowly jovial police inspector with the distinct impression that “one [man]” simply can’t find all the explanations to the madness around him, nor conjure up any way to defeat it. As Lang observed the rise of the Third Reich around him, and his film wound up being suppressed in his home country for nearly 20 years, it’s easy to imagine he might concur with that sentiment.

Next time: He has directed two films that have grossed over $300 million domestic. She has starred in two films that have grossed over $300 million domestic (well, almost). The one film they made together barely grossed 1/10th of $300 million. Superheroes, angsty vampires, and interactive - possibly life-threatening - board games are all on board for a jam-packed Chapter Two.