Viking Night: Tron

By Bruce Hall

August 31, 2010

BoxOfficeProphets.com

With a sequel due to open this winter, you’re going to hear more and more people rhapsodizing about how much they've always loved Tron and have desperately looked forward to a second installment for years. I am here to tell you that nine out of ten times you hear someone say that, you will be listening to a lie. Tron is a film that was pioneering in many ways, from its obvious technical achievements to the fact that in a forward thinking move for the time, a promotional video game was released along with it. But upon its release it perplexed as many people as it impressed, and the arcade version of the movie was considerably more popular – and profitable - than its big brother. Though the film itself turned out to be a modest financial success, Disney considered it a disappointment and all but divorced it, even getting out of the live action movie business entirely for about a decade. Because of this, public awareness of Tron waned over the years and misperception of the film as a complete failure put off serious talk of a sequel until the turn of the century. And as much as the franchise’s devoted cult following would like to take credit for that it was more than likely a financial decision, and an ironic one at that. It was most likely the success of CGI driven extravaganzas like The Matrix that convinced Disney that they’d been on to something in the first place – had there been no Tron, Neo, Morpheus and Agent Smith might never have existed. So what IS the deal with Tron, and why should you care? Well lace up your Chuck Taylors, brush out your mullet and settle back into a bean bag. Allow me to take you back to a time when computers and the people who used them were little more than a curiosity, and the idea of using either to make a movie seemed completely ludicrous.

Kevin Flynn (Jeff Bridges) is a hot shot computer programmer, banished from the nefarious Encom Corporation for pressing the issue when a rival coder pirated his work and parlayed it into a promotion. Relegated to living in a loft over the video arcade he now owns, he spends his free time hacking into the Encom mainframe, trawling for the evidence that will clear his name. After he runs afoul of system security, two of his former coworkers drop by the arcade to warn Flynn that he’s now in danger. What’s worse, Alan (Bruce Boxleitner) and Lora (Cindy Morgan) paint a bleak picture of Encom’s corporate culture since their friend was forced into exile. Flynn’s nemesis Ed Dillinger (David Warner) has become CEO of the company and is using the Master Control Program (MCP) he created to impose dictatorial authority over the other programmers, stifling creativity and innovation. It’s become a terrible place to work, and it quickly becomes clear to the trio that their interests overlap. If Flynn can prove that Dillinger is guilty of theft they can topple him from power, restoring Flynn’s good name and giving his colleagues back their freedom. To this end, they sneak Flynn back into the building and place him at a secure terminal where he can dig up the files he needs, but in doing so he attracts the attention of the infamous MCP. Dillinger’s pet program has outgrown its creator, evolving into a ruthlessly malevolent entity that runs the company with an iron fist and even harbors designs on world domination. Not eager to be upstaged by a mere human, the MCP uses a conveniently placed experimental laser to digitize Flynn into the mainframe, where it intends to gleefully torture and kill the one man who can stand in its way.

If this sounds a little obtuse today, imagine how it must have played to audiences almost 30 years ago. Flynn and his friends accurately embody the stereotypical nerd-tastic personality most people even today associate with computer enthusiasts - but their confusing techno-babble must have been a little off putting to even the savviest moviegoers at the time. At any rate, what could easily have been the most boring corporate espionage thriller ever made quickly rises to a whole new level when Flynn enters the "game grid" of the computer mainframe. Here, the MCP’s efforts to take over the system are represented by programs facing each other in sadistic gladiatorial combat. Programs themselves are represented by avatars that resemble their creators, giving Flynn some welcome company when he runs into Alan’s security program called – surprise! - Tron, and Lora’s rather dull system maintenance subroutine. Together they lead a digital insurgency to free the system from the MCP and restore autonomy to all programs. Those who rebel against the MCP insist on worshiping the humans – or Users - who created them, forming a religious cult of sorts. When Flynn is revealed to be one of these Users, he attains Messianic status among the other programs, becoming de facto head of the resistance. This lends him a remarkable set of physical abilities that are never fully explained, but in the spirit of science fiction you’ll want to just accept this. People can travel faster than light, everyone everywhere speaks English, and in the computer world Kevin Flynn can leap nested-if statements in a single bound. Tron eventually becomes less a movie about computers and more a homily on the evils of corporate conformity and the virtues of faith and freedom of thought. This mish-mash of ideas makes for an admirable stab at allegory but all the clumsy Spartacus style discourse on self-determination is really more than a film like this is equipped to handle.

Director Steven Lisberger and producer Donald Kushner tried very sincerely to create something primarily about overcoming tyranny – the cutting edge special effects were viewed simply as a natural extension of the message they were trying to convey. But the film’s philosophical underpinnings are too often sabotaged by some laughably poor dialogue and an almost nonexistent level of character development. Like any film this one has its share of weaknesses, and if you wanted to dwell on them you could levy any number of additional criticisms against it. If Dillinger was smart enough to create a super intelligent AI powerful enough to take over the world, why did he need to steal ideas from Flynn to get ahead? If Encom was such a bad place to work, couldn’t everyone have just taken their big brains over to Microsoft? And despite its generally likeable cast, the film’s performances are merely serviceable, if little more. Jeff Bridges brings his trademark anarchic flair to Flynn which is good, because the script gives him little to go on. Bruce Boxleitner was reportedly a little uncomfortable with the material and if true, it shows in his performance. But Alan’s inherent skepticism serves as a convincing foil to Flynn’s paranoid bluster – the contrast of personality actually ends up working fairly well. Master Thespian David Warner is probably the standout, as he gets to play three roles here and they’re all the sort of diabolically evil bastard that every actor dreams of playing at least once. Tron has its flaws to be sure, but as an experiment in flirting with the impossible it succeeds brilliantly. What audiences saw up on the screen in 1982 was something they’d never seen before and really have never seen again – it was a once in a lifetime experience that was special primarily by virtue of being unprecedented.

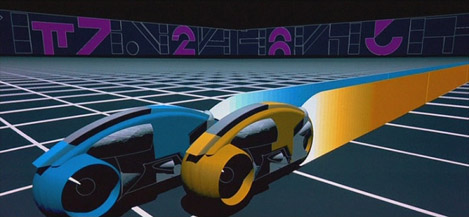

But there’s just only so much you can stuff into a movie at once and in some ways Tron nearly shudders under the weight of its own lofty ambitions. Fortunately for us all, the real star of the show is the innovative special effects, which appear somewhat quaint by today’s standards, but still bear a unique look and feel that has never been duplicated. Much is made of the movie’s groundbreaking use of CGI and it still impresses me what they were able to accomplish with such limited technology. But here’s a little known fact – in 96 minutes of running time, every CGI shot in Tron strung together end to end barely adds up to 15 minutes. The majority of the visuals you see in this film are traditional hand drawn animation and photographic treatments that are meant to resemble digital effects. The reason for this isn’t just about cost – there was simply no way at the time to combine CGI and live action in the same shot, so the film’s technical team came up with some incredibly creative workarounds for this that gave the film its memorable look. By the time the dazzling climax comes around, you’re really less interested in whether or not these paper thin characters ever earn their freedom as you are in how spectacularly shiny and colorful it all looks! It really is similar to watching a more traditional Disney classic like Cinderella. It is impossible not to note how dated it looks, but the quality achieved was nothing short of timeless by contemporary standards.

While I enthusiastically welcome the sequel, I wonder... Tron came into being despite a great deal of force being arrayed against it. And the technical challenges involved with creating the film spurred the sort of fierce creativity that you don’t see enough of these days in Hollywood. But today, high quality digital effects shouldn’t be a pleasant surprise; they are expected. Nobody doubts that Tron: Legacy will effectively live up to the visual standard set by its predecessor, but if the story doesn’t carry any more water than the original, it might be hard to care. When all is said and done, I think that Tron’s greatest asset is its sunny optimism and damn-the-torpedoes can-do attitude. This was a movie that refused not to be made, and the pioneering creative drive of everyone who fought to make it a reality is evident in every frame. What Tron lacks in gravitas it more than makes up for in style, energy and momentum – it is still fun to watch and despite its age it still has an adventurous sense of freshness that’s sadly lacking in far too many films today. And even had a sequel not been green-lighted and Disney had kept the thing buried in Walt’s backyard, the fact remains that Tron sparked a revolution in film that might not have happened otherwise. The crowd pleasing digital eye candy we all take for granted today might never have happened, or perhaps The Lord of the Rings would have been made in 2025 instead of 2001. So go ahead - lace up your Chuck Taylors, brush out your mullet and settle back into a bean bag – and raise a Jolt Cola to Tron, the little movie about computers that could not be killed. To paraphrase one of the film’s most ear splittingly dreadful lines of dialogue: “You can remove people like us from the system, but our spirit remains in everything you create!”

Truer words were never spoken. Put that in your pipe and smoke it, mister high and mighty Master Control.