Classic Movie Review: The French Connection

By Josh Spiegel

BoxOfficeProphets.com

The French Connection is one of the rarest Best Picture winners I’ve ever seen, and a great example of a movie that can win an Oscar and still be an action movie of sorts. No, we’re not talking about something like Transformers here, but there’s no denying that The French Connection, directed by William Friedkin (who won an Oscar for his work), is a procedural in many senses of the word. For whatever reason, what I kept comparing the movie to while I was watching is the HBO series The Wire. The Wire is a great television program that’s about the gritty of the world of crime, seen from the eyes of cops and criminals. That show is frequently compelling, if not always filled with heated interrogations, shootouts, and so forth. Now, make no mistake: The French Connection has plenty of action, but it is also meant to be as realistic as possible.

Take the film’s signature scene, a breathless car chase through the streets of Brooklyn. The context is this: Hackman’s character, Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle, a hard-bitten New York cop, is frantically trying to catch a French hitman who just tried to kill him in broad daylight in front of innocent bystanders. The hitman is also heavily tied to drug trafficking that Popeye is trying to stop; he’s currently riding a subway train, trying to outrun the angry detective. Popeye is trying to drive faster than the train, to beat the hitman to the next stop on the subway line. The stakes aren’t incredibly high, but when you watch the scene from the point of view of the car’s windshield - and see trucks, vans, and sedans slam into the car Popeye’s commandeered - it’s hard not to unconsciously grab onto something in suspense.

In most movies, the car chase would go on and the car Popeye drives wouldn’t get hit, or it’d barely get hit. Here, the car’s not so lucky, and Popeye looks worse for wear. The end of the scene is a well-known image of the film, where Popeye shoots the hitman in the back as he runs up the stairs to the subway platform. What gets us to that point is one of the most appropriately lauded chase scenes in film history. I’d heard plenty about it beforehand, but was shocked to realize that I was still freaking out when I saw Popeye come this close to running over a woman and the cradle she’s pushing down the street. Friedkin’s you-are-there-no-seriously-you-are-really-there style of directing is still unique today, and should be envied by anyone who calls themselves an action movie director.

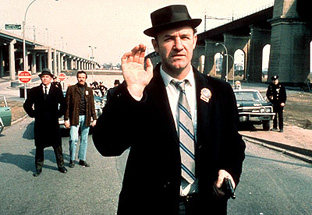

So if The French Connection’s a procedural with a killer action scene, why the hell did it win Best Picture? In some ways, The French Connection was a breath of fresh air when it released, a wild success with audiences and critics, thanks in no small part to the singular and powerhouse performance from Hackman, whose stardom began there. Though he’s far campier in Superman, a big reason for him being in the film and feeling like an appropriately intimidating villain was his bullying role as Popeye Doyle, a tough cop whose single-minded nature is both a help and a hindrance. He doesn’t make many friends, he’s casually racist, he beats people up to get what he wants, but he also wants to uphold the law. Popeye may not seem so different than cops such as Vic Mackey from The Shield, but remember that Popeye came first, and was toughest when he was around.

The plot of The French Connection, while intriguing, is almost an afterthought, as you’re just so engrossed by the performances from Hackman and the late Roy Scheider as his partner, nicknamed Cloudy. These two would get bigger in the years to come, but their chemistry here is enjoyable, even if Cloudy is far less pushy than Popeye. If ever there was an ideal good cop, it was this guy. They’re both trying to track down the men behind a huge shipment of heroin coming in from France, and have targeted a seemingly small-time crook who runs a candy store and may be ushering in the drugs. Their superiors are doubtful, but let Doyle and his partner take point on the investigation as the plot unfolds. But it’s really about Hackman here.

Just as listening to Hackman yell is a joy, it’s a crushing disappointment to me (and should be to any other fan of movies and great actors) not only that he’s apparently retired from acting, but that his last film will apparently be the 2004 comedy Welcome to Mooseport. You remember that movie, don’t you? Of course you do! Who didn’t see this great comedy, pitting Hackman against Ray Romano? Yeah, yeah, none of you saw it (I did, though, and it was bad, bad, bad), but the point is, he could have bowed out the year before, with his role in the merely okay legal drama Runaway Jury. That one’s not a classic, but it does feature Hackman with Dustin Hoffman, which is an interesting match, and better than Hackman and Romano.

Still, Gene Hackman had a great career (and hopefully, he’ll poke his head out for another movie before he passes on), winning Oscars for his work in The French Connection and in Unforgiven, and for memorable roles in Superman, The Poseidon Adventure, Hoosiers, and one of my favorite movies, The Royal Tenenbaums (sample of Hackman’s raised voice: “YES, I AM! I think you’re having a nervous breakdown!”). One of the best aspects of his style of acting is that it’s nonexistent. We can look at actors like Al Pacino and either laud him or take him to task for his frequently manic, over-the-top rantings, but with Hackman, there’s something unusual and uneasy to define. He had screen presence, to be sure, but he managed to, in later years, mask coiled rage behind a charming smile and folksy voice.

In The French Connection, he’s a guy so intimidating that he can walk into a bar populated with muscular, tough-looking guys and when he yells at them to get against the wall, they don’t even hesitate. Doyle is someone who can be underestimated, but never should be. Though he’s not a perfect person (there are allusions to his stubborn work being the cause of a cop’s death), and he may not be someone you’d want to get a drink with, Popeye is an undeniably fascinating lead character you’re rooting for, and not just because he’s wearing a badge. I wouldn’t say that the entirety of The French Connection is as classic and iconic as his performance (the French criminals aren’t as compelling, unfortunately), but the movie succeeds chiefly because of Friedkin’s style and Hackman.

In The French Connection, Gene Hackman proves that he’s tough. In the years to come, he’d prove how versatile he was. The following year, he’d go on to star as the conflicted yet heroic priest in The Poseidon Adventure; though his character was histrionic, you got the feeling that Hackman was always in control of his performance. He’d be known as the outsized Lex Luthor in the Superman films, as the cruel sheriff in Unforgiven, as the coach in Hoosiers, all because he proved early on that he could do anything. Who else could be as funny as he was as a blind man just trying to help a monstrous man, as he was in his cameo in Young Frankenstein? Still, it’s worth noting that, from the first time I saw the film, as soon as I heard his unmistakable voice, I worried that something bad would happen to the monster. Even when he’s not playing a tough guy, Gene Hackman could always exude the aura of someone who should not be screwed around with.