A-List: Auteurs

By Josh Spiegel

July 2, 2010

BoxOfficeProphets.com

Whether you’re a fan of Shyamalan now or you were at one point (I’m in the latter camp, having given up all hope after the one-two-three knockout punch of crap known as The Village, Lady in the Water, and The Happening), there is one thing we really shouldn’t debate too much: the man is an auteur. As you probably know, the auteur theory hearkens back to France in the 1950s, where it was argued that movies, despite being made by many people, speak with the voice of the director, or the auteur (or author). So, even though Lady in the Water was worked on by people aside from Shyamalan, all you need to do is look at one minute of the movie and know that it is undeniably an M. Night Shyamalan movie, filled with faux portent, stilted acting, pretentious dialogue, and a cameo from the director. This week’s A-List looks at five other, and far better, auteurs.

Alfred Hitchcock

I like to imagine that, after the excrescence that was Lady in the Water, wherein Shyamalan appeared as a man whose writings would be so important in the future that they would literally save the world, the ghost of Sir Alfred Hitchcock haunted Shyamalan and bullied him into either never making a cameo appearance or barely showing his face in one of his movies ever again. Shyamalan, of course, was tipping his hat (or ripping off, depending on your view) to Hitchcock’s famous habit of showing up in each of his great movies, but only for a second or two. In the classic suspense film North by Northwest, he shows up right after the opening credits as a man who misses a bus; in Psycho, he’s a passerby wearing a cowboy hat. In Lifeboat, the 1940s thriller set entirely on…a lifeboat (duh), he appears in a newspaper ad someone is skimming past.

This cameo style is but one of the many things that set Hitchcock apart from his fellow directors, and as an auteur (and one of the favorites of many of those French film critics who thought up the auteur theory). From the icy cool blonde femme fatales, the beleaguered male leads, the very thought of an innocent man or woman being accused of something they did not do…the list goes on, but the point is that you can start watching Vertigo halfway through (although why in the world you would want to is beyond me) and know immediately that it’s an Alfred Hitchcock movie. Even to surface elements, such as using famous actors like James Stewart and Cary Grant multiple times, proves Hitchcock’s auteur status. He’s one of the first and best.

Frank Capra

Is there a more American, a more patriotic director than Frank Capra? You may throw out directors such as John Ford or Howard Hawks, but if the American spirit is full of such schmaltzy yet friendly images as apple pie on Independence Day, then Frank Capra is the quintessential American filmmaker. He is well remembered for such classics as Mr. Smith Goes To Washington and It’s a Wonderful Life, movies that celebrate the human spirit, stories that remind us what it means to live in this country. There are some people who might feel the need to gag on such boldly and baldly sentimental films, movies such as Mr. Deeds Goes to Town and You Can’t Take It With You, but his films are an important touchstone in cinema. Without Capra, do we get the James Stewart of the 1950s? Do we get screwball comedies half as good as It Happened One Night?

Capra is best known for his collaborations with Stewart, and for his propaganda filmmaking for the United States military during World War II. Though the word propaganda may make you cringe when thinking of the American war effort, there’s no question that Capra’s documentary filmmaking, captured in the Why We Fight series, is propaganda of the highest order, just something that might be seen now as necessary for the time. Capra’s work is always noted by its folksy nature, its celebration of the common man, and its excoriation of greed (see Mr. Smith Goes to Washington if you need further proof). When you think about the upcoming holiday, there’s no better auteur to highlight than Frank Capra.

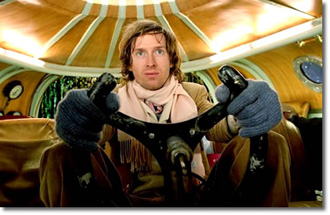

Wes Anderson

Of the many current auteur directors, Wes Anderson might be the most divisive. He’s perhaps the most obvious working director to choose, because just about everyone who watches and appreciates movies only needs to look at a freeze-framed image from one of his films, whether it’s Rushmore or The Darjeeling Limited, to know it’s one of his films. Anderson’s style is well-known; you may call it fussy or twee, or you may embrace it, as I do. Whatever the case, Anderson is an auteur, not only because he has such a strong hand in the scripts of the films he directs, but for the many hallmarks apparent in his filmography. Even when he’s working on a stop-motion animated adaptation of a Roald Dahl story, you can count on Anderson finding a way to get a quirky, memorable soundtrack of songs from the 1960s and 1970s into the picture.

Other notable standbys of Anderson’s films are certain actors, from Bill Murray (who’s made an appearance of some kind in each of the man’s films, except for his debut, Bottle Rocket) to Owen Wilson (a frequent writing collaborator) to Jason Schwartzman. Another great staple of Anderson’s work (to me, at least) is his use of space, and the idea that shooting a film in widescreen doesn’t mean there shouldn’t always be plenty to look at. Various shots from The Royal Tenenbaums, The Life Aquatic, and even Fantastic Mr. Fox provide a feast for the eyes, as long as you know where to look for the various details. Anderson has detractors (and though I’m not one of them, I readily admit that he’s a director you either love or hate), but his style is one of a kind, even if others have tried to copy him unsuccessfully.

Woody Allen

Forty years and forty movies. There are actors who’ve been in plenty more movies, but for a director to make that many movies, and to do so at such a steady, unwavering pace, is unheard of. Steven Spielberg is one of the biggest, most famous directors in the world, and he can’t say he’s made as many movies in less time (and Spielberg has managed to twice, in the past decade, release two movies per year). No, it’s Woody Allen who can say he’s done this, make 40 movies in 40 years. What makes the task so amazing is that Allen, while a well-known face to most people in the country and a beloved director in plenty of places overseas, doesn’t make wildly successful films. Most people know the man, but mostly for his personal life. Some may have seen Annie Hall or Manhattan, but mention Interiors, Zelig, or even The Purple Rose of Cairo (my pick for his most underrated film), and they look at you blankly.

That said, most people would probably be able to identify one of Allen’s films on sight. If the man himself doesn’t feature prominently, then you can bet that there will be an actor who stars in the film as a Woody Allen stand-in. Even Melinda and Melinda, his 2005 comedy-drama, managed to make funnyman Will Ferrell into the Allen character. There will be plenty of one-liners, nebbish characters, jazz music, a New York setting (with the notable exception of some of his recent films), awkward yet honest romantic storylines, and every once in a while, you might get a character talking directly to the camera. Allen’s films are so many that he’s not able to boast a perfect record (as of late, he’s not been that fantastic, in my opinion), but when you’ve made such classics as Annie Hall and Crimes and Misdemeanors, it’s almost worth giving a pass to this insightful comic.

Stanley Kubrick

For me, it’s the character glowering at me. This is what defines a Stanley Kubrick film to me. Think of the many male characters who have done this in Kubrick’s works: Dave Bowman in 2001, Jack Torrance in The Shining, Pyle in Full Metal Jacket, Alex in A Clockwork Orange. A Stanley Kubrick film is known for many things, but it’s one of the main characters glaring upwards at the camera that always shakes me. Kubrick is one of the most hailed directors, having brought films such as Dr. Strangelove, Lolita, Eyes Wide Shut, and the aforementioned works to audiences everywhere. Unlike the other directors on the list, Kubrick was more isolated and his works considered colder and more distant. That doesn’t mean that his movies aren’t immediately unique and singular.

Kubrick died in 1999, before his final film, Eyes Wide Shut, was released, but his spirit managed to live on with the Steven Spielberg sci-fi film A.I., which Kubrick had intended to direct before he passed away. A.I. is one of Spielberg’s most divisive films, but it is not only worth watching, but it’s pretty damned haunting if you take a little time to ponder what’s actually happening in the final half-hour, which is often derided by those who aren’t fans of the film. Kubrick’s vision still lingers through Spielberg’s camera, the Pinocchio story in a post-apocalyptic future. Though his films aren’t truly lovable, they are all worth cherishing and frequently unforgettable, noted by the unflinching eye to violence, the harsh statements on the human race, and Kubrick’s beautiful and striking use of the camera.