Viking Night: Trainspotting

By Bruce Hall

March 9, 2010

BoxOfficeProphets.com

In order to appreciate Trainspotting the first time you see it, you might benefit from already being a certain type of person. Perhaps you're a rudderless 20-something who considers your very existence to be a nihilistic thumb in the eye of everything that is good and decent. If so, you might be attracted primarily by the film's colorful characters and their youthful defiance. On the other hand, a more discerning critic might welcome the way Trainspotting manages to retain such an even tone despite covering such a grim topic. It juggles bleakness and glibness in almost equal measure but it ably offers an uncompromising view of drug abuse and urban decay without openly passing judgment either matter. And then of course, there is the mainstream moviegoer who will quickly point out that Trainspotting is exactly what I just described - a film about drug abuse and urban decay - things the average person wouldn't care to experience even for 90 minutes! It is probably true that the majority of us tend to view movies (if not all forms of entertainment) as pure escapism, meant to be enjoyed within the cozy boundaries of our relatively predictable and ordinary lives. There's certainly nothing wrong with that; it's difficult for us to expose ourselves to things outside this comfort zone, because we often think there's nothing to be gained by going there. Few of us wish to be challenged by everything we experience, but arbitrarily binding yourself to incuriosity risks depriving you of something more valuable in the long term. We aren't allowed to experience just one side of our own lives, so taking a walk through someone else's existence – warts and all – is occasionally a good way to gain an appreciation of yourself and of everyone around you.

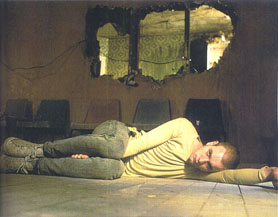

Based on the novel of the same name, Trainspotting is such a journey, chronicling the life and times of a close group of friends in economically depressed Edinburgh, Scotland during the 1980s. The film's narrative is told through the eyes of Mark Renton (Ewan McGregor), an affable but chronically derelict young man living with his parents post adolescence. With jobs scarce and entertainment options even more so, Renton and his closest pals entertain themselves by abusing heroin and milking the pubic aid system – interviewing for jobs often enough to receive a stipend but never quite working hard enough to actually land one. When times are truly tough, the boys fund their painful addiction through petty theft, rarely thinking twice about who they steal from or what they take. They wander aimlessly through the wilderness of young adulthood, adamantly determined not to "choose life". To them, obtaining a job, owning a home, having a family and accepting the basic responsibilities of life are pointless things, with the reason being that death eventually comes to us all whether we are productive members of society or not. Seduced by the convenience of fatalism, Renton and his lads convince themselves that the pursuit of an honest living – not drug abuse – is the fool's errand. Renton alone is able to admit to himself that they live the way they do because it's simpler than finding a job. In the short term, taking drugs simply feels better than punching a clock and in the end, giving up on life is just a whole lot easier than living it.

Understanding this, Renton makes repeated efforts to quit heroin but is hampered at every turn by the influence of his so called friends. There is Sick Boy (Johnny Lee Miller), an amoral con-man who would gladly steal money from his own mother, in the event he could locate her. Spud (Ewen Bremner) is the follower of the group, a kind hearted but simple lad who is obsessed with winning the approval of others. Begbie (Robert Carlyle) is less a friend than he is a dangerously unstable sociopath who requires an obedient entourage. And then there's Tommy (Kevin McKidd), a comparatively untainted, impressionable young man who doesn't use drugs but being fascinated by the lifestyle, hangs around with the gang anyway. Easily the most thoughtful and articulate of this bunch, Renton still finds it difficult to extricate himself from the tempest of drugs, petty crime and self induced poverty he and his friends inhabit. Despite his best intentions he finds that it feels good to be bad - and not only are his friends all inveterate enablers, but they tend to bring out the worst in one another. Lifelong friends usually share many of the same interests and values - but this is a group of people whose interests are merely vice, and whose values are virtually nonexistent. When sober, they have almost nothing in common and are barely able to tolerate one another's company - and when under the influence of either heroin or alcohol, the only thing they truly share is their inebriation. As much as anything, Trainspotting is a film about doomed friendships and weak people who overcome their frailties with dependencies. And that's one of the most fascinating aspects of Trainspotting, the fact that the concept of dependency is approached from a number of different directions and shown to have a variety of causes. One could almost say that despite being a "drug film," at its heart it isn't really about drugs at all.

There is a broader theme addressed by Trainspotting and it is that we are all at one time or another, in times of weakness or doubt, driven to cling to things. But there are habits and there are vices, and it isn't always easy to agree on which is which, or how it is that we become enslaved by them.

Sick Boy has never told the truth in his life, and the fact that he's chosen deception as a way of life has left him a sad, lonely person without any true friends. Eventually the one good thing he does have going for him is tragically lost in the midst of a hedonistic drug binge.

Spud seems to be vaguely aware of his limitations, but his lust for approval ensures that he's always in the wrong place at the wrong time and he always seems to be paying for things others have done. Begbie is a haunted man who never knew his parents and is motivated principally by the white hot furnace of rage that misfortune has sparked inside him. His every waking moment is devoted to punishing the world for what he's become and predictably, it causes nothing but trouble for those closest to him. Tommy and Renton seem to be the closest in temperament, but Tommy is emotionally dependent on his girlfriend and the thrills they get from hanging around their rowdy friends.

So, when one of Renton's good natured pranks goes terribly wrong, Tommy inevitably finds himself at a dangerous crossroads and the path he chooses comes to have far reaching consequences for everyone. And the theme of emotional subjection isn't limited to youth - Renton's parents choose to turn a blind eye to their son's activities until it is too late. His mother soothes her guilt with the "socially acceptable" sin of Valium; his father uses a proud man's stubborn sense of denial.

Yet, Trainspotting never casts aspersions on these characters; it simply presents them in an unvarnished way and lets their actions speak for themselves. Still, for some, it may be easy to specifically isolate and demonize Renton and his mates for using heroin, and for others the film's backdrop of economic collapse makes it simple to excuse the sins they see. But addictions are typically a facade, meant to conceal a far more painful burden. Fundamentally, none of these characters seem able to harbor much hope for the future, and they each choose their own destructive way to deal with this. One man's heroin habit is another man's drunkenness is another man's anger, but the outcomes are invariably negative and the theme is a common one.

Whenever we replace long term responsibility with guiltless, short term solutions, the consequences almost always return to haunt us in the end. Whether a good person is made bad by an addiction or a bad person chooses to live irresponsibly, their lives inevitably align in the same direction. Trainspotting suggests to us that most of its characters may actually be good people on some level, but for the choices they've made. And we are given the not so subtle suggestion that for each of them, dependence itself isn't the problem so much as it is a byproduct of the real issue – the fact that they've given up on themselves.

It's occasionally difficult to watch, but the film almost always has a sense of earnestness that makes you want to believe that just maybe things are going to turn out well for these people. The film has an intentionally surreal quality, so that despite the terrible things that occasionally happen to its characters, there remains light at the end of the tunnel, if only they'd turn toward it. In fact, Trainspotting is often criticized for suggesting that one can indulge in bad habits and still have a good time.

We do see Renton and his friends enjoying their extended drug binges, drinking themselves senseless, laughing and living the responsibility-free lifestyle that entails a good hard addiction. But it isn't a secret that drugs can and do make you feel good - that's why most people who take them do, and to deny this would be disingenuous. But even addicts know that the high is artificial, and the irony is that the obvious downside of drug abuse is all the more chilling, once you have seen the upside.

The phony sense of ecstasy one feels from a drug is rivaled only by the indescribable horror of withdrawal. A junkie cannot experience one without the other and a film chronicling the life of one can't either – if it purports to be honest. But brilliant direction by Danny Boyle and an outstanding performance by an ideal cast allow the film to portray the peaks and valleys of its protagonists without lingering at one extreme or the other. Despite the constant drumbeat of misfortune in their lives, each of these individuals at one time or another feels touchingly human, making their camaraderie feel endearing and their debauchery seem sad but genuine. We feel as though we're allowed to pity them without absolving them, laugh at them without condoning their actions and loathe them without ever turning on them. To be honest, every time I see Trainspotting it seems about 30 minutes too short!

The characters as written should be familiar to most people, because even if you've never known someone with an addiction, we all have dependencies at one time or another and they tend to affect us in similar ways. After all, there's a little bit of everyone in everyone, which is the root of compassion and understanding. An occasional willingness to experience the world through the eyes of someone we do not understand is one way to do that and it can make every day - or at least a 90 minute film like Trainspotting - a more illuminating experience.

By the end of the film we get the sense that despite their many hardships there may be hope for Mark Renton and his friends. Not all of them, but maybe for some of them. We may not have the ability to choose our circumstances, but we all have the opportunity to determine how we respond, and we all bear primary responsibility for our own fates. For this reason, it's easy to believe that despite the hardships we all face day to day, there's hope for most of us, too.