Viking Night

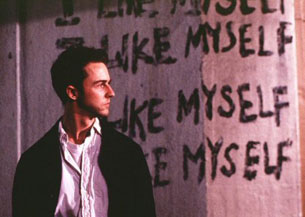

Fight Club

By Bruce Hall

February 23, 2010

BoxOfficeProphets.com

I felt confused, as I'd been under the impression that as two red blooded American males with an HDTV and several hours to kill, we were going to watch something that involved sports, jet planes, ninjas or giant robots. After a series of furtive glances, my friend explained that there was "nothing on" any of the at least 350 HD channels available. I had my doubts about that, but suggested that we didn't have to watch television - to which he responded there was "nothing else to do." Here we were, two members of the same species that invented Democracy, the internal combustion engine and the space shuttle, rotting away on a couch in a Midwestern suburb because there was "nothing to do." I was raised to believe that if you think there's "nothing to do" it's because you're too lazy to do anything. But there was more to it than that. If there's "nothing to do" but watch television, is having a better television going to solve your problem? Have we really been so thoroughly trained to believe that the things we already have aren't good enough and that if only we replaced them with new ones our lives would improve?

We exist in the wealthiest, most advanced society the world has ever seen, and we have access at any time to almost anything we'd like to eat, drink or experience. If you have an Internet connection, almost the sum total of human knowledge is at your fingertips at any given time. Yet despite this, so many of us are constantly bored, unhappy, restless and disillusioned. We have "nothing to do" – other than toil away thanklessly at jobs we don't want, struggling to pay off the mountain of debt we've accrued for all of the wonderful things we have but don't need. Granted, this doesn't describe everyone, but it's hard to deny an ever growing identity crisis amongst our middle class. As more of us acquire the ability to have the things we've always wanted we often find that having the things you want only makes you want to have more of the things you don't. At times, it seems as though the larger and more complex the world becomes, the smaller and more insignificant is our shared humanity. Some say that we've exchanged meaningful human interaction with the need to indulge ourselves in material wanderlust – and that this has created a class of people constantly on the verge of despair. This is in part the subject of Chuck Palahniuk's 1996 novel Fight Club, and the 1999 film of the same name.

Jack (the central character does not actually have a name) is a product recall analyst for a major automobile manufacturer. Years of remorselessly translating human deaths into statistical data have left him riddled with guilt, which he tries to soothe by burying himself in his work, accumulating nice clothes and flashy furniture. Additionally, the constant travel has left him suffering from chronic insomnia. Jack is a miserable person who derives his sense of identity from his job, his income and his worldly possessions. He's unhappy living this way, but he can't imagine any other way to live. On the advice of a doctor, he begins attending self help groups and quickly becomes fascinated by how insignificant his own pain seems against the suffering of others. Soon, he begins attending clinics for terminal and chronic diseases – not because he is dying, but because it helps him reconnect with his humanity. And no doubt, seeing someone worse off than you is a temporary but effective way to feel a little better about almost anything. But Jack's newfound sense of well being is shattered when a mysterious girl begins shadowing him.

Marla is clearly the same sort of person as Jack; not bodily ill but spiritually empty, and he initially hates her for it – the sort of hatred that makes it clear how much he's attracted to her. But Marla's presence reminds Jack that he's just hiding from reality and not really taking productive steps to solve his problems. After a brief confrontation, she would seem to be out of his life for good, although Jack takes conspicuous care to ensure that he might see her again. But the damage is done, and Jack's desperation – and insomnia – has returned. Things begin to seem hopeless again until Jack takes a fateful business trip. Through a highly unusual series of events, he becomes acquainted with a mysterious stranger named Tyler Durden, who seems to share Jack's disenchantment with the human condition. They become fast friends and after an evening of drunken revelry, discover that they find bare knuckle boxing to be an exhilarating form of liberation. Fight Club is born, and it isn't long before scores of other rudderless, angst ridden middle class men have joined the ranks. Much like professional fighters, the competition is their release; overcoming the will of another gives them a sense of accomplishment and belonging.

The fisticuffs in Fight Club are a source of controversy, as the boxing matches are raw, and occasionally graphic. The scenes are intentionally unsettling; however, the violence in Fight Club is meant primarily to be metaphorical. This is a story mainly aimed at men, and one of the central themes is the idea that successive generations of the able bodied have been raised in a world that really does not require their participation. Tyler Durden suggests that the machinery and institutions of our society generally function on their own, regardless of who runs them or who is subject to them. Men now have nothing to build, nothing to struggle for and nothing to overcome. We work so that we can afford to fill our homes and lives with pointless diversions and amusements, distracting us from the repetitive nature of our existence. For a species programmed to be hunters and gatherers, this is a fate worse than death. Tyler argues that Fight Club gives these men what they need – a challenge and an outlet – and that they're better for it. At first, Jack agrees and feels that he has at last found meaning in his life. And then, things change.

Ultimately, Tyler manages to bring Marla back into Jack's orbit, forcing Jack to struggle with his allegiance to Tyler and his obvious feelings for Marla. Ever the charismatic, nihilistic firebrand, Tyler has bigger plans for Fight Club than just an underground forum for pent up male aggression. Before long, Jack finds himself at the mercy of forces he helped to create but can no longer control. His sense disgruntlement returns and in ways he could never have predicted, he is forced to stop blaming society for his problems and finally take responsibility for his fate. In the end, Jack comes to realize that Fight Club was just as much a diversion as his television, his treadmill, or his Rislampa wire lamps made of environmentally friendly unbleached paper. It becomes obvious that personal fulfillment and self determination are just that – something that must come from inside an individual and on an intimate level, rather than being dependent on where you work, what you own, who you know or to what group you belong.

Fight Club is one of those movies that seems to give everyone who sees it exactly what they want. Some see a grand philosophical exposition on the themes I've described above, holding up the film as a searing indictment of consumerism gone amok. Others see a mindless orgy of homoerotic violence, while still others see a twisted, post noir romance. To me that's the mark of a great story, when what you see in it depends on your background and values. But it's human nature to project what you already think onto what you see every day. In my mind, Fight Club is just about a lonely guy who does think about all of these things and does feel crushed by them. Yet fundamentally, all he wants to do is all that most of us want - connect with someone. But his over-indulgence in self pity leaves him vulnerable, and lets him become consumed by his own despair. It's a dilemma that at some point in our lives we all can identify with. The story doesn't entirely succeed on all levels, as it occasionally becomes enamored with itself, bogged down by Tyler Durden and his deranged machinations. This dilutes the film's message somewhat and runs the risk of making it seem like an endorsement of aimless, sociopathic aggression.

But I think that when you're using a work of fiction to convey an idea, resorting to extremes can be an effective way of making sure that whether or not your audience understands your point, they at least devote some time to considering it. Many of us do settle for that we can get in life, simply because we're too afraid to risk trying to achieve what we really want. If we have misgivings about it we often appease them with denial, material goods or intellectual pabulum designed to keep us docile and incurious. The extremes depicted in Fight Club are meant to make us consider the choices we have. Many of us are like Jack is when we meet him. We are reluctant to admit that we're unhappy, but lack the will to act - meaning we'll always be miserable. Others – like Tyler Durden – lash out at the world, able to identify the problems in it but unable to offer constructive solutions. Perhaps the best thing we can do is try to keep a sense of perspective on what's truly meaningful and what is nothing more than a distraction to our development.

As Tyler Durden might say, the things you own often end up owning you. You are not your job; you are not how much money you have in the bank, you are not the car you drive, and you are not your 47 inch HDTV. You are for better or worse, what you make of yourself. And your life, for better or worse, will be what you've designed it to be.