Chapter Two: Barcelona

By Brett Beach

February 11, 2010

BoxOfficeProphets.com

Whit Stillman's second film, Barcelona, was released in 1994, four years after his Academy Award-nominated debut Metropolitan and nearly a half-decade prior to his third (and most recent) feature, The Last Days of Disco. With no new credits of any kind since then, Stillman has been largely absent from the fiction filmmaking scene for as long as James Cameron's decade-plus lag between Titanic and Avatar, albeit with considerably less press and a much lower profile. An interview given last month at Sundance indicates the gap is not intentional or self-inflicted but the result of the all-too-typical frustrations that can stall any filmmaker - projects that don't come to fruition for any number of reasons, but primarily economic ones; and being pigeonholed as a director who makes a certain kind of movie that may not currently be, if it ever was, in box office vogue. In Stillman's case, that kind of movie is literate, intelligent, drolly funny and (some would say too, too) verbose. Put simply, it's the type of film it is easier for many to admire rather than like, and for most to go about blithely unaware of.

There is more than enough plot in each film, but via Stillman's presentation (he wrote, produced and directed all three) they are defiantly not plot-driven and suffer at times from slack narratives. Driven by characters and dialogue, it is virtually impossible to tell from the beginning how they will enfold and towards what end the plot strands will resolve. That being said, his films are distinct enough to be recognizable in the way that the works of Tarantino or Mamet are. His characters alternate between complete certainty and paralyzing hesitance, struck with the tendency of the severely over-educated to imagine that they have all the answers, yet resigned to doing naught but spinning wheels and endlessly reciting their knowledge, their theories and their just-out-of-reach aspirations. Noah Baumbach captured a lot of the same elements in his sublime 1995 debut Kicking and Screaming, about post-collegiates terrified of life outside of undergrad-dom. Where Baumbach's feature trafficked in the encapsulating moment where embarrassment and self-loathing meet with pop-culture overload, Stillman's creations fall more on the winsome side of the line.

His three features form a loose thematic trilogy that has been referred to as the "nightlife films" but could also be crudely captured with the tag line "young Americans on the make." All three are set in vaguely specific moments over the last 20 years - Barcelona's title card situates it sometime during "the last decade of the Cold War" - which lends them all an intentional air of nostalgia as well as a fable-like quality. And yet, being set in the recent past dates none of them. This is due to Stillman's refusal to rely solely on the period trappings of costume and music to make the mood and vibe more palpable. There are nightclub scenes in Barcelona and Disco and brief glimpses of the city nightlife just out of reach of the teenagers in Metropolitan, but Stillman wasn't setting out to make an I Love the '80s time trip. His refusal to stop just shy of locating any of the films in a specific year or time helps to open them up that much more. (Roger Avary adopted a similar technique with his adaptation of Bret Easton Ellis' The Rules of Attraction, albeit with the sort of characters who would blowtorch Stillman's Sally Fowler Rat Pack denizens and snort them up in a line of coke.)

Barcelona is not only the middle film, but, surprisingly, the highest grossing of the three. It got the widest release of any of Stillman's films (nearly 300 theaters at its high mark) and grossed nearly $8 million in the summer and fall of '94 against a $3 million budget. Both Metropolitan and Disco accumulated about $3 million each, which was great for the former on a low six-figure production cost, but not as much for the latter, which failed to recoup even half of its financing. I credit Barcelona's success partly on word-of-mouth but also on a poster campaign that smartly put supporting actress Tushka Bergen's visage front and center with the implied promise of sexy fun time not far behind. The uninitiated may have wondered about the two men sitting on steps in the background, one in a suit, the other in a naval officer's uniform and sporting a fine looking eye patch. I could grumble about the poster giving away too much with that image, but a lot of that comes from hindsight, like wondering about the silhouetted frogs poking out from the borders of the early Magnolia poster ads.

Barcelona is also by far the most political, conversely the least universal, and truth be told, the weakest of the three, which again adds to my curiosity at how it wound up grossing the most. I have viewed Disco enough times in the last ten years to validate it in my mind as Stillman's best, but I was curious as to my reaction on checking out Barcelona for the first time in many moons. It can perhaps best be represented as the only film of his with a body count and bodily harm (at least more so than just bruised egos and crushed dreams.)

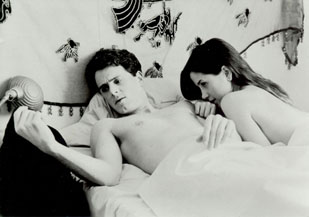

Barcelona concerns itself with Ted (Taylor Nichols) and Fred (Chris Eigeman) a pair of Midwest cousins with a fairly thorny family history (mostly predicated on Fred's habit of "borrowing" money and then not repaying it back, and of concocting amusing lies about Ted to tell any girls interested in his cousin). Ted, a salesman from Chicago, has been in the titular city for some time as the film opens when Fred, a self-proclaimed "advance man for the Sixth Fleet" arrives in town needing a place to crash. The introverted and bookish Ted, who surrounds himself with self-help literature and is prone to dancing to big band music while reading the Holy Bible (!), falls back into familiar patterns of argument and exasperation with the more brash and outgoing Fred. Soon the pair is dealing not only with their individual reputations, but their status as unwanted outsiders in a climate increasingly unfriendly towards Americans. All this while they attempt to woo the local trade-show girls.

Nichols and Eigeman are a pair of delightful character actors who were part of the ensemble in Metropolitan and just about the only ones to parlay their debuts there into long-running careers. Eigeman was also in Kicking and Screaming and the sweet, offbeat and short-lived late ‘90s ABC sitcom "it's like, you know . . ." and he and Nichols between them have guested on seemingly half of the Big 4 networks' series in the last 15 years. Eigeman has the essence of the eternal man-child mixed in with his persona of the sharpest guy in the room while Nichols convincingly captures the "good-guy" nebbish who seems so quiet yet tightly wound, he's liable to burst into violence. Not sure if he ever has in any roles but the signs are definitely there. They could have had quite the fruitful career as the mismatched odd couple, but I am thankful they didn't pull a Sutherland/Gould post-M*A*S*H and reunite for increasingly less worthy projects. They are perfectly at home with Stillman's dialogue and one could be forgiven for thinking the auteur created them along with the story.

Where his first and third films felt like true ensembles, particularly where the male and female interactions were concerned, Barcelona doesn't have any character depth beyond the two leads. This is particularly humbling to observe when one of the female leads is Mira Sorvino, only a year before she won the Oscar for her performance in Mighty Aphrodite. She and Bergen seem, well, bland, not particularly in their performances but in the women they are playing, as if Stillman couldn't quite them to be more than tertiary outlines. Both are involved with Ramone, a local political writer for a major newspaper, and a large plot of the hinges on just how sincere the women are in their affections for the cousins. Stillman deserves points for focusing on the political as well as the personal and for bringing the real world threat of violence into what could have been just a smart, wounded love story. But an unexpected plot twist about two-thirds of the way in helps to further the romantic entanglements more than it provides a push towards deeper consideration of the anti-American, anti-military, and anti-capitalist anger with which Stillman surrounds the characters.

If I sound unduly harsh on Barcelona, it's only because I compare it to two great films and it is "merely" a good film. Watching Metropolitan or Disco, I feel like hugging myself with delight over how well crafted the characters are, how individual yet recognizable they seem, and how the film is happy to observe and follow along wherever their journeys may take them. As sunny and lush as Barcelona is (cinematographer John Thomas has done all of Stillman's films as well as a large part of the Sex and the City oeuvre, including both films), it ultimately feels slightly distant and remote, as if even its writer/director wasn't sure what kind of happy ending he was striving towards. The final moments are abrupt and unfocused and leave one with the sense that more (or perhaps less) needed to be said.

Next time: This 1992 release was both prequel and sequel to the television show it came from, a fact that's only slightly less confusing than the film itself.