AFInity: A Clockwork Orange

By Kim Hollis

October 23, 2009

BoxOfficeProphets.com

Perhaps one of the best-known, most widely discussed lists is the American Film Institute's 100 Years... 100 Movies. A non-profit organization known for its efforts at film restoration and screen education, the AFI list of the 100 best American movies was chosen by 1,500 leaders in the movie industry and announced in its first version in 1998. Since then, the 100 Years... 100 Movies list has proven to be so popular that the AFI came forth with a 10th anniversary edition in 2007, along with other series such as 100 Heroes and Villains, 100 Musicals, 100 Laughs and 100 Thrills.

In addition to talking about which films are deserving of being on the list and bitterly shaking our fists because a beloved film was left out, we also love to brag about the number of movies we've seen. As I was looking over the 100 Years... 100 Movies list recently, I realized that I've seen 47 - less than half. As a lover of film and writer/editor for a movie site, this seemed like a wrong that needed to remedied. And so an idea was born. I would watch all 100 movies on the 2007 10th Anniversary list - some of them for the first time in as much as 20 or more years - and ponder their relevance, worthiness and influence on today's film industry. With luck, I'll even discover a few new favorites along the way.

#70: A Clockwork Orange

It's been 20 years since I have seen this 1971 Stanley Kubrick feature. At the time, I had recently read the book on which it is based for a class on 20th century British literature and written a research paper about the thematic use of music in the novel. I decided to go ahead and watch the film adaptation to see how it compared, and I remember being blown away. To my mind, it was a spot-on rendition of author Anthony Burgess's work, perfectly capturing the atmosphere and characters. And yet, I never watched the film again until this week, despite having viewed other Kubrick pictures like The Shining, Paths of Glory, The Killing and Dr. Strangelove numerous times. The AFI lauds A Clockwork Orange on the 2007 version of its 100 Years... 100 Movies list (it appeared on the original as well) and also ranks it highly on 100 Years... 100 Thrills, 100 Years... 100 Heroes and Villains, and has it as the #4 sci-fi film. Would I be as impressed by it today as I was when I was a more impressionable young lass?

Truth be told, I started out thinking it didn't have nearly the impact that it did then, though I suspect that's due to my growth as a human being and consumption of copious amounts of literature, music and film since that time. As a naïve college student, I hadn't had the opportunity to experience many classic films, and now that I have, A Clockwork Orange just looks very, very good as opposed to "Oh my gosh! It's the most amazing movie I have ever seen in my entire life!"

Even with that said, it's a movie that stays with me and keeps me pondering its ideas after the fact. Additionally, its usage of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony - both in its original and updated formats - has lodged the soundtrack and score solidly in my brain, and I'm having some trouble shooing it away.

The movie is set in a dystopian Britain, where gangs of young men flout the law and run about stealing, raping, assaulting, and generally engaging in whatever mayhem suits them. The film's central character is Alex DeLarge, the leader of such a gang. He appears to be deeply intelligent, but also psychotic. He revels in his anarchic splendor and seems to be completely lacking in remorse or conscience.

Alex's world is thrown into turmoil after he bludgeons a woman to death with a sculpture of a penis (yes, you read that correctly). Fed up with his cruelty (to them), his gang members betray him and throw drugged milk in his eyes, causing him to be temporarily blinded. Alex is arrested and sent to prison, where he volunteers for a revolutionary new rehabilitation process known as the Ludovico Technique. Effectively, he is drugged and then forced to watch videos of various violent acts, causing him to become ill whenever an urge to do "bad things" comes to his mind. The film circles around to showing Alex encountering many of the people he injured or wronged, and the consequences of these encounters are dire indeed.

One of the things that I truly admire about A Clockwork Orange is its examination of "goodness". It's certainly true that Alex is not a "good" person. He's a thief and a rapist who sponges off his parents and cares only for himself and his own pleasure. And yet, there may be only one person in the film who can truly be classified as "good". Obviously, none of Alex's friends are "good," even though two of them eventually become police officers. His parents turn away from him when he is released from prison and actually incapable of doing wrong - but also unable to defend himself. He's a pawn of a variety of political types who hope to turn his plight into a symbol for their various causes (there's no distinction between conservative and liberal here. All are guilty). The only person who really seems to have benevolent motives is a chaplain in the prison. He takes a genuine interest in Alex and seems to be trying to help him in his reform, and also strongly objects to the Ludovico Technique on the grounds that it eliminates free will. But ultimately, we do have to question whether Alex is indeed the most "evil" intended person in the film.

Another fascinating aspect of A Clockwork Orange is its emphasis on youth versus experience. The young people in the film speak a jargon all their own; it's incomprehensible to someone not in their crowd. (My memories of basic Russian tell me that this vocabulary derives from that language. Therefore, a word like "horrorshow" used to express a positive makes sense to me since it sounds like the Russian "chorosho", which means something akin to "splendid"). The divide between generations is as significant as Baby Boomers and Gen X-ers to my mind, and a prescient foretelling of things to come. The film illustrates the attitudes that can lead to a generation gap.

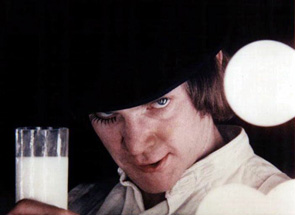

Along with the themes of the film, A Clockwork Orange has a singular look and sound. The characters are dressed in things like codpieces and black top hats, and Alex wears fake eyelashes on one eye. When they disguise themselves for criminal activity, they wear odd masks with long noses or other strange exaggerations. A rival gang has its own look. Various set pieces serve to give the film a futuristic feel. It's a story that could happen any time, but we're very aware that it's set at some not-so-distant time.

The music also contributes to the atmosphere of the movie, with the music of "Ludwig Van" taking center stage. Like most young people, Alex loves music, but rather than having an obsession with some modern flavor of the day, he's particularly attached to Beethoven's Ninth. Fragments of this symphony play throughout the film, and they're modernized with Walter Carlos's moog synthesizer updates at various points (it's impossible to experience this film without having the moog synth version of the Fourth movement getting stuck in your head for days). The piece proves to be extremely important to the plot of the movie, though I won't reveal the reasons why for those who have yet to view A Clockwork Orange for themselves.

Along with the direction, the movie's success rides largely on the performance of Malcolm McDowell as Alex. It's remarkable how he is able to be charismatic and appealing even as his character is completely repulsive. You're not rooting for him, precisely, but there is an undeniable energy whenever he is onscreen that precludes you from looking away. In a lot of ways, Alex DeLarge is the granddaddy of such characters as American Psycho's Patrick Bateman and even Heath Ledger's Joker.

Interestingly, the more I've reflected on the film as I've written this article, the more I've come back to my original conclusion that it's a brilliant piece of celluloid. The violence (particularly against women) is so disgusting that it's difficult to call A Clockwork Orange a re-watchable movie, but it's also not as though these actions are being condoned. To the contrary, even if Alex is appealing, we're revolted by him. I like that I was originally captivated by its thematic use of music, but 20 years later, I'm more intrigued by A Clockwork Orange's examination of "goodness" and the schism between generations. Ultimately, that's exactly the sort of thing an excellent movie should do - grow with you.

Kim's AFInity Project Big Board