Before Their Time: The Fountain

By Daniel MacDonald

April 2, 2009

BoxOfficeProphets.com

Among this roll call of high-minded science fiction is Darren Aronofsky's 2006 masterpiece The Fountain. Premiering at the Venice Film Festival to both a chorus of boos and a standing ovation, this meditation on mortality, love, and science managed to split critics' opinions right down the middle, registering 51% Fresh on RottenTomatoes.com's Tomato Meter. Despite a reported budget of only $35 million - shockingly low for such an ambitious film, involving space travel and three distinct time periods - the movie was not a financial success, garnering $16 million in worldwide box office receipts during its theatrical run. The Fountain was largely ignored by the moviegoing public.

The movie had a troubled production history: in 2002, Brad Pitt and Cate Blanchett were set to star in a $70 million version, and a number of expensive sets had already been constructed when Pitt backed out, citing concerns over the script. Financing was pulled, the production shut down, and the outlook was bleak. Two years later, Aronofsky had regrouped, rewritten the script, and recast the picture with Hugh Jackman and Rachel Weisz taking the leads. The budget was trimmed by half, necessitating a great deal of creativity to be used in creating special effects that would otherwise be the domain of prohibitively-expensive computer graphics.

Yet, the budgetary strain and recasting with less recognizable actors may well have contributed to The Fountain becoming a superior film to what it might have been (although Pitt would surely have secured a more profitable opening weekend). When concepts are the stars of the picture, as is the case with The Fountain, it can be beneficial for an audience to not be distracted by superficial elements ('Hey look, Brad Pitt is bald!').

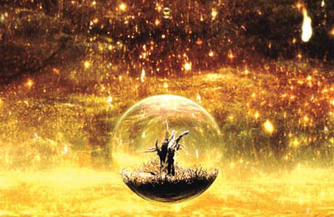

The Fountain is a single story told through three plot lines set at different periods in time. In present day, Tommy Creo (Jackman) is a medical researcher developing experimental treatments using the sap from a Guatemalan tree with the hopes of developing a cure for brain tumours. Tommy's wife, Izzi (Weisz) is dying of a tumour herself, and Tommy is sure that he will find a way to save her life. Izzi is writing a book involving a conquistador named Tomas, which we see play out in 16th century Spain. Tomas (Jackman again) is tasked with finding the Tree of Life by his queen Isabella (Weisz), and sets out on a dangerous adventure to save her from death at the hands of the Grand Inquisitor. Intercut with these two tales is the journey of Tom (Jackman), a hairless, tai chi practicing astronaut who is hurtling through space in a clear, spherical spacecraft, his only companion a dying tree. Tom is trying to reach a nebula that he believes will resuscitate both the tree and Izzi, whose image haunts him.

It's a heavy story that jumps frequently between the three time periods, with repeated framing devices, lighting, and dialogue creating a unified, powerful, emotional experience for the viewer. Aronofsky clearly has something to say, especially about the need to accept death as an essential and defining part of life, which is why his protagonist Tommy is so hell-bent against doing so. At one point, Tommy calls death a disease that can be cured, like any other, and it's here that we see the extent to which a person can delude himself because of love for another.

There's an awful lot to chew on in The Fountain, with a foundation built upon, among other inspirations, metaphysics, Mayan folklore, and the Bible; it's not difficult to see how some might be overwhelmed by its ambition. On paper, perhaps The Fountain could be dismissed as a heartless intellectual exercise. But, like Steven Soderbergh's Solaris, the film is first and foremost an emotional journey seeking to explore universal human truths about our fear of death. The metaphors come fast and furious (but, fortunately, sans Vin Diesel), yet it's not necessary to understand every moment or pick up on every reference. This is a movie to get swept up by.

Visually, The Fountain is a tour de force, with every frame carefully considered, a distinct, constrained lighting scheme and color palette, and the depiction of events that humans could never see up close. Especially impressive is Tom's journey through space: chemical reactions were shot by a macro photography specialist, then optically laid over the starfield through which Tom's craft speeds to create an ethereal, other-worldly beauty, and the climax involving an exploding star recalls 2001's heart-pounding final minutes while establishing itself as a unique, definitive vision of celestial activity.

While The Fountain is far from dumbed-down for its audience, it's more accessible than one might think thanks to its organic, honest emotional core. Yes, the best sci-fi films are about ideas, but they're also about people. The Fountain doesn't forget that, which makes it one of the most emotionally satisfying pictures I've ever seen. While it still may not have found its audience, I expect ten years from now a new crop of filmmakers will emerge having been blown away by its craft, citing The Fountain as a defining film that inspired them to want to make movies for a living.