Snapshot: November 13-15, 1992

By Joel West

January 30, 2009

BoxOfficeProphets.com

Now that Twilight has gone on and become the highest grossing vampire movie ever ($185 million), it is time to take a look back at the film that proved the genre could be highly profitable in the modern era after a lull in the late '80s and early '90s.

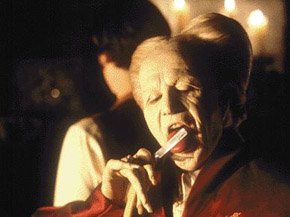

Vampire movies have always maintained relevance in film, as a column on the subject would not be complete without mentioning the iconic vampire portrayals of Max Schreck (1922's Nosferatu), Bela Lugosi (1931's Dracula), Christopher Lee (1958's Horror of Dracula) and Klaus Kinski (1979's Nosferatu the Vampyre). To an extent, these films harbored a social significance during their respective eras, and the '80s were certainly no exception. With the onslaught of AIDS throughout the '80s and early '90s, it was hard to not see vampire films as a metaphor for society's anxieties. Since the content of the genre's films would be more than some pale schmuck biting women on the neck, filmmakers took novel approaches to reflect society's fears without sacrificing an entertaining time at the movies. In return, some of the genre's best films came out of the '80s (1983's The Hunger, 1985's Fright Night, and 1987's Near Dark and The Lost Boys). Treating vampirism as a disease mirrored the era's trials with AIDS and drug addiction and their impact resonated with filmgoers and critics alike. After The Lost Boys' modest run ($32 million), however, vampire films hardly made a sound at the box office. In the summer of '92, a high school comedy disguised as a vampire film was building buzz as a potential breakout for the genre. While Buffy the Vampire Slayer would provide the concept (and name) years later for one of the best TV dramas ever, a box office sleeper it was not ($16 million). Clearly the genre was not translating very well in the '90's.

On the other hand, anyone that went to the movies in the summer of 1992 did see the subtle marketing for a vampire film that would soon turn the genre on its head.

Prior to the Internet age, movies could up and surprise you and Bram Stoker's Dracula was no exception. In July of 1992, posters started popping up in theater lobbies featuring a gargoyle's head with the words Beware over it. Not long after, the very meaning of teaser trailer started playing before the summer's blockbusters. Puddles of blood were seen running together (very reminiscent of the special effect used in the previous year's blockbuster Terminator 2) with quick cuts to the film's cast. Wait a minute, was that Winona Ryder? Oh my God, did I just see Anthony Hopkins? What the hell is Keanu Reeves doing in this? Then, Francis Ford Coppola's name is revealed and audiences knew they were in for a treat (please note, this was before Coppola wrecked his artistic credibility with Jack and The Rainmaker). Suddenly, Bram Stoker's Dracula's release date, aptly the Friday the 13th in November, was marked on everyone's calendar.

Not to say there wasn't any type of buzz following Coppola's Dracula as it was being made. Controversy with the studio over how Coppola wanted the film to look, on-set tension between the film's leads Ryder and Gary Oldman (his first big leading man role as Dracula), and rumored poor test screenings had all the makings of box office disaster. In fact, the film was even playfully dubbed The Bonfire of the Vampires. Not the kind of noise the iconic filmmaker wanted around his $40 million horror film. Furthermore, the film was far from a sure thing to begin with. The Godfather III aside ($66 million), Coppola hadn't steered a film to outright blockbuster status since 1979's Apocalypse Now ($78 million). While Oldman was coming off 1991's JFK ($70 million), he had never been tasked to carry a film on his own with such high expectations. Reeves and Ryder still weren't established stars; not to mention the fact that Reeves was clearly overmatched by the material. Only Hopkins was the real draw, coming off the previous year's Best Picture, Silence of the Lambs ($130 million). Still his name hadn't proved profitable earlier in '92 with Freejack ($17 million). This was coupled with the fact that the genre was in the box office doldrums. There really wasn't much going for Bram Stoker's Dracula.

Which just reinforces the importance of marketing.Dracula would have numerous opportunities to get its name out there in the fall of '92.

Through the end of September up until the weekend before Dracula opened, a number of R-rated films held the top spot at the box office. The Last of the Mohicans ($75 million), Under Siege ($83 million), and Passenger 57 ($44 million) were all providing adult audiences some escapism from the family-oriented blockbusters of the summer. Throw in the sleeper-hit horror film Candyman ($25 million) and Dracula had two months to prepare the right audience for Coppola's vision. The full-length trailer was masterfully cut (some could argue even better than the final product), showing the film's selling points (Hopkins, top-notch special effects, buxom Vampire brides, atmospheric sets) prominently. This was simply a vampire film audiences had yet to see; while fitting perfectly into the '90s theme of "bigger is better."

The week leading up to film's release was generating the type of water cooler buzz the studio was hoping for. You simply couldn't change the channel without seeing an ad for the film. In fact, most viewers probably couldn't even get Oldman's contagious laugh that shown in the film's commercials out of their heads (it has been 16 years and I still hear it!).

Dracula was without a doubt going to open big, the only question was how big?

When the final ticket was punched, Bram Stoker's Dracula had pulled in a massive $30.5 million over its first three days. At the time, it was the biggest non-sequel R-rated opening ever and biggest ever opening for a non-summer film (surpassing Back to the Future II's $27.8 million in 1989). All the turmoil and bad buzz that initially plagued Dracula was not enough to overcome the exceptional marketing. The trailers conveyed an epic horror film that was helmed by one of the greatest directors ever and clearly struck a nerve with moviegoers. Now the question was how much would the film make over its entire run? It would easily top $100 million, but how about $150 million? Is $200 million possible?

Reviews for the film were mixed; some claimed Coppola had returned to form, while others felt it was overdone, overlong, and worse...boring. Audiences tended to lean towards the latter as poor word-of-mouth quickly ripped out the legs from under Dracula. Dropping a rather drastic – by 1992 standards, when movies weren't as frontloaded as they are now – 51% in its second weekend (still $15 million); Dracula's high forecasted expectations were slowly diminishing. Adding insult to injury, its claim to largest non-summer opening was short lived, as Home Alone 2 pulled in $31.1 million the following weekend. After the Thanksgiving holiday, Dracula quickly became a non-factor at the box office and finished its run with a still very healthy $82.5 million.

While not the box office behemoth it could have been, Dracula did start a resurgence of classic horror monster and vampire films. In November 1994, both Mary Shelley's Frankenstein and Interview with the Vampire attempted to bleed audiences of the millions Dracula reaped two Thanksgivings before. A key similarity between these films and Dracula was certainly the talent involved. Previous incarnations had B-movie talent, while these films had critically hailed directors (Kenneth Branagh and Neil Jordan) and A-list actors (Robert DeNiro and Tom Cruise). The end result varied considerably with Frankenstein flopping pretty hard ($22 million) and Interview with the Vampire not only surpassing Dracula's opening ($36 million) but even eclipsing the century mark (final total was $105 million). The vampire genre has since oversaturated the market with notable hits (the Blade and Underworld franchises), a few flops (Vampire in Brooklyn, Bordello of Blood) and everything in between (Van Helsing, Vampires, 30 Days of Night, From Dusk till Dawn). No one would argue the influence that Bram Stoker's Dracula had on the genre over the last 16 years.

The Verdict: Bram Stoker's Dracula resurrected the vampire genre to what it is today by injecting a talented filmmaker, an epic and atmospheric tone and very clever marketing. Vampire films ever since have not strayed too far from that formula (a shout-out to Guillermo del Toro's debut film, Cronos, as being a notable exception). Unfortunately, Dracula also established the pattern of a heavily front-loaded opening followed by a quick exit from the Cineplex.