Movie Review: Control

By Matthew Huntley

November 15, 2007

BoxOfficeProphets.com

This is such a sad, grave and discouraging film. But it's also beautifully raw, poetically photographed and contains some of the best performances of the year. It's the best kind of biopic because you walk away feeling as though you really knew about the people being documented. Ian Curtis' life isn't romanticized but instead placed within our reach. Corbijn narrows the gap between Curtis' world and our own so that we can empathize with this poor soul. Take it from someone who's mostly ignorant about this film's subjects that it connects with viewers the way few films do.

Sure, the film rides a conventional wave in terms of its overall structure, but it crescendos toward a great emotional power. Even if the characters and situations were created from scratch instead of re-enacted, it would have played just as effectively because Corbijn makes Control work as a story first and foremost. The facts and accuracy are beside the point.

What's interesting about Ian Curtis (Sam Riley), at least in the way the film depicts him, is that he's not a "typical" junkie or a womanizer. The Hollywood biopic has become so conventional that audiences expect their subjects to be archetypal drug users with out-of-control libidos. And while such stories can work wonderfully on film (Ray, Walk the Line), it seems the studios are only willing to tell them a certain way. Curtis' story is different from most because, unlike Ray Charles or Johnny Cash, he was practically a child at the height of his career.

When we first meet Ian, he's a quiet recluse who finds inspiration and peace of mind through David Bowie and Iggy Pop. At 18, outside a Sex Pistols concert, he meets Peter Hook (Joe Anderson), Stephen Morris (Harry Treadaway), and Bernard Sumner (James Anthony Pearson), and they form a band called Warsaw. At their first recording session, Curtis changes their name to Joy Division (it refers to women in Nazi concentration camps who prostituted themselves for soldiers on leave; the name was originally described in the novel The House of Dolls).

After a successful gig that gets the crowd jumping, the group hires Rob Gretton (Toby Kebbell) as their manager, and thanks to Curtis insulting Tony Wilson (Craig Parkinson), eventually make their way onto Wilson's television show, So It Goes. They go on to self-release their first extended play and tour around Europe. Eventually, Gretton books them for a two-week tour around America they'd never end up playing.

But Control isn't about Joy Division as much as it is Curtis' personal battles with his declining health, epileptic "fits" and his relationship with his young wife, Deborah, whose book, Touching From a Distance, was the basis for Matt Greenhalgh's screenplay.

Deborah is played in the film by the incandescent Samantha Morton, and she deeply loves Ian, but she is perhaps naive because the two married as teenagers. This hasty decision, among many others, likely contributed to Curtis' mental breakdown because he started to think he couldn't live dual lives as a family man and rock star. At one point, he must face the idea he doesn't love Deborah anymore, but his guilt prevents him from enjoying himself as a musician. His epilepsy, lack of sleep, and dependence on medication lead him down a road of seemingly endless sadness.

Even Ian's baby daughter makes him believe he's a failure because he can't always be there for her and the band at the same time. We're given a lot of this information because the real Deborah Curtis also produced the film. A great deal of how we see Ian is from her point of view, which suggests not only the film contains pure truth, but a perspective only the person closest to Ian could provide.

It also touches on Ian's affair with a Belgian reporter named Annik Honoré (played by the beautiful Alexandra Maria Lara). Surprisingly, the film doesn't simply shove Annik aside and label her a floozy. She too loves Ian the way Deborah does and Riley and Lara share such tender, unaffected scenes that I never wanted them to end. They were so calm and honest because the two simply talk. We believe everything coming out of their mouths is real, especially when Annik confesses how scared she is she might be falling in love with him.

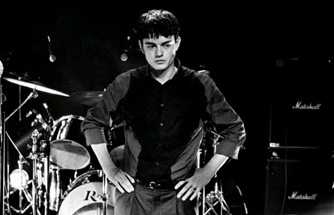

I mentioned how I knew nothing about the real Ian Curtis, but even with that said, I could tell Sam Riley's performance was so much more than an imitation. A friend of mine told me Riley nailed Curtis' signature dance in which he wildly and seemingly without rhythm swings his arms on-stage. But Riley never looks as though he's trying to look like somebody else. His behavior feels natural. Not once did I ever feel like I was watching an actor going through the motions. Riley becomes, simply, this troubled young man and evokes such stark, raw emotion that he deserves an Oscar nomination.

But good performances also depend on the focus and enthusiasm of the director, and it's clear Anton Corbijn has nothing but love and affection for his main character. Corbijn is obviously a huge fan of Joy Division and knows in his heart just how influential Curtis would have become. His ode to this small icon is like a heartfelt thank you, a manifestation of Corbijn's bittersweet memory of a tortured soul.

From a technical standpoint, the film is also beautiful to look at. It was shot in color but transferred to black and white, no doubt to symbolize Curtis' meek outlook as he neared his end. The soft focus suggests that everything Curtis saw was only right in front of him. He never gave himself a reason to look toward the future.

One of the many, many things Corbijn gets right is the way he captures Curtis' depression, or at least the idea of depression. There is a shot where Curtis watches television because it is, in his mind, the only thing to do. He stares aimlessly into the tube then turns it off. This is such an honest representation of a depressed state, where people suffer because they don't know what to do next and every fiber in them feels lost. They feel they have nowhere to go but down.

True, Curtis' behavior was often immoral, but Corbijn and Riley manage to make him a sympathetic individual whom we identify with and care for. From the film's point of view, Ian was a kind and gentle person who, like many depressed individuals, started to believe he was no longer living for himself, and no matter what decision he made, he believed he was going to let somebody down. In the end, he was convinced everybody hated him and the pressure and fear of those thoughts eventually got him at a young age. Curtis had lost control, and it resulted in one of life's great tragedies.